DECIDING TO WRITE A LITERARY ANALYSIS.

DECIDING TO WRITE A LITERARY ANALYSIS. In a traditional literary analysis, you respond to a poem, novel, play, or short story. That response can be interpretive, looking at theme, plot, structure, characters, genre, style, and so on. Or it can be critical, theoretical, or evaluative — locating works within their social, political, historic, and even philosophic neighborhoods. Or you might approach a literary work expressively, describing how you connect with it intellectually and emotionally. Or you can combine these approaches or imagine alternatives — reflecting new attitudes and assumptions about media.

Other potential media for analysis include films, TV shows, popular music, comic books, and games (for more on choosing a genre, see the Introduction). Distinctions between high and popular culture have not so much dissolved as ceased to be interesting. After all, you can say dumb things about Hamlet and smart things about Game of Thrones. Moreover, every genre of artistic expression — from sonnets to opera to graphic novels — at some point struggled for respectability. What matters is the quality of a literary analysis and whether you help readers appreciate the novel Pride and Prejudice or, maybe, the video game Red Dead Redemption. Expect your literary or cultural analyses to do some of the following.

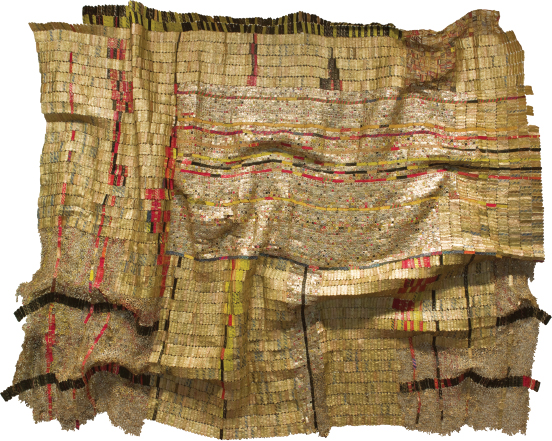

Duvor Cloth (Communal Cloth) The Ghanaian artist El Anatsui builds his remarkable abstract sculptures from street materials, including metal fragments and bottle caps. He explains, “I believe that artists are better off working with whatever their environment throws up.”

El Anatsui (Ghanaian, born 1944), Duvor Cloth (Communal Cloth), 2007, aluminum and copper wire, 13 × 17 ft. Indianapolis Museum of Art, Ann M. Stack Fund for Contemporary Art, 2007.25. © El Anatsui/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Begin with a close reading. In an analysis, you slow the pace at which people in a 24/7 world typically operate to examine a text or object meticulously. You study the way individual words and images connect in a poem, or how plot evolves in a novel, or how complex editing shapes the character of a movie. In short, you study the calculated choices writers and artists make in creating their works. (read closely)

Make a claim or an observation. The point you want to make about a work won’t always be argumentative or controversial: You may be amazed at the simplicity of Wordsworth’s Lucy poems or blown away by Jimi Hendrix’s take on “All Along the Watchtower.” But more typically, you’ll make an observation that you believe is worth proving either by research or by evidence you discover within the work itself.

Use texts for evidence. An analysis helps readers appreciate the complexities in creative works: You direct them to the neat stuff in a poem, novel, drama, or song. For that reason, you have to pay attention to the details — words, images, textures, techniques — that support your claims about a literary or cultural experience.

Present works in context. Works of art respond to the world; that’s what we like about them and why they sometimes change our lives. Your analysis can explore these relationships among texts, people, and society.

Draw on previous research. Your response to a work need not match what others have felt. But you should be willing to learn from previous scholarship and criticism — readily available in libraries or online. (plan a project)