Introduction: Working with Historical Sources

The long history of Western civilization encompasses a broad range of places and cultures. Textbooks provide an essential chronological and thematic framework for understanding the formation of the West as a cultural and geographical entity. Yet the process of historical inquiry extends beyond textbook narratives into the thoughts, words, images, and experiences of people living at the time. Primary sources expose this world so that you can observe, analyze, and interpret the past as it unfolds before you. History is thus not a static collection of facts and dates. Rather, it is an ongoing attempt to make sense of the past and its relationship to the present through the lens of both written and visual primary sources.

Sources of The Making of the West, Fourth Edition, provides this lens for you, with a wide range of engaging sources—from a Mesopotamian epic to a political cartoon of the Old Regime to firsthand accounts of student revolts. When combined, the sources reflect historians’ growing appreciation of the need to examine Western civilization from different conceptual angles—political, social, cultural, economic—and geographic viewpoints. The composite picture that emerges reveals a variety of historical experiences shaping each era from both within and outside Europe’s borders. Furthermore, the documents here demonstrate that the most historically significant of these experiences are not always those of people in formal positions of power. Men and women from all walks of life have also influenced the course of Western history.

The sources in this reader were selected with an eye toward their ability not only to capture the multifaceted dimensions of the past but also to ignite your intellectual curiosity. Each written and visual document is a unique product of human endeavor and as such is often colored by the personal concerns, biases, and objectives of the author or creator. Among the most exciting challenges facing you is to sift through these nuances to discover what they reveal about the source and its broader historical context.

Interpreting Written Sources

Understanding a written document and its connection to larger historical issues depends on knowing which questions to ask and how to find the right answers. The following six questions will guide you through this process of discovery. Like a detective, you will begin by piecing together basic facts and then move on to more complex levels of analysis, which usually requires reading any given source more than once. You should keep these questions in mind every time you read a document, no matter how long or how short, to help you uncover its meaning and significance.

1. Who wrote this document, when, and where?

The “doing” of history depends on historical records, the existence of which in turn depends on the individuals who composed them in a particular time and place and with specific goals in mind. Therefore before you can begin to understand a document and its significance, you need to determine who wrote it, and when and where it was written. Ultimately, this information will shape your interpretation because the language of documents often reflects the author’s social and/or political status as well as the norms of the society in which the author lived.

2. What type of document is this?

Because all genres have their own defining characteristics, identifying the type of document at hand is vital to elucidating its purpose and meaning. For example, in content and organization, an account of a saint’s life looks very different from an imperial edict, which in turn looks very different from a trial record. Each document type follows certain rules of composition that shape what authors say and how they say it.

3. Who is the intended audience of the document?

The type of source often goes hand in hand with the intended audience. For instance, popular songs in the vernacular are designed to reach people across the socioeconomic spectrum, whereas papal bulls written in Latin are directed to a tiny, educated, and predominantly male elite. Moreover, an author often crafts the style and content of a document to appeal to a particular audience and to enhance the effectiveness of his or her message.

4. What are the main points of this document?

All primary sources contain stories whether in numbers, words, and/or images. Before you can begin to analyze their meanings, you need to have a good command of a document’s main points. For this reason, while reading, you should mark words, phrases, and passages that strike you as particularly important to create visual and mental markers that will help you navigate the document. Don’t worry about mastering all of the details; you can work through them later, once you have sketched out the basic content.

5. Why was this document written?

The simplicity of this question masks the complexity of the possible answers. Historical records are never created in a vacuum; they were produced for a reason, whether public or private, pragmatic or fanciful. Some sources will state outright why they were created, whereas others will not. Yet with or without direct cues, you should look for less obvious signs of the author’s intent and rhetorical strategies, as reflected in word choice, for example, or the way in which a point is communicated.

6. What does this document reveal about the particular society and period in question?

This question strikes at the heart of historical analysis and interpretation. In its use of language, its structure, and its biases and assumptions, every source opens a window into its author and time period. Teasing out its deeper significance will allow you to assess the value of a source and to articulate what it adds to our understanding of the historical context in which it is embedded. Thus, as you begin to analyze a source fully, your own interpretive voice will assume center stage.

As you work through each of these questions, you will progress from identifying the basic content of a document to inferring its broader meanings. At its very heart, the study of primary sources centers on the interplay between “facts” and interpretation. To help you engage in this interplay, let us take a concrete example of a historical document. Read it carefully, guided by the questions outlined above. In this way, you will gain insight into this particular text while training yourself in interpreting written primary sources in general.

Henry IV, Edict of Nantes (1598)

The promulgation of the Edict of Nantes in 1598 by King Henry IV (r. 1589–1610) marked the end of the French Wars of Religion by recognizing French Protestants as a legally protected religious minority. Drawing largely on earlier edicts of pacification, the Edict of Nantes was composed of ninety-two general articles, fifty-six secret articles, and two royal warrants. The two series of articles represented the edict proper and were registered by the highest courts of law in the realm (parlements). The following excerpts from the general articles reveal the triumph of political concerns over religious conformity on the one hand, and the limitations of religious tolerance in early modern France on the other.

Modernized English text adapted from Edmund Everard, The Great Pressures and Grievances of the Protestants in France (LONDON, 1681), 1–5, 10, 14, 16.

Henry, by the grace of God, King of France, and Navarre, to all present, and to come, greeting. Among the infinite mercies that it has pleased God to bestow upon us, that most signal and remarkable is, his having given us power and strength not to yield to the dreadful troubles, confusions, and disorders, which were found at our coming to this kingdom, divided into so many parties and factions, that the most legitimate was almost the least, enabling us with constancy in such manner to oppose the storm, as in the end to surmount it, now reaching a part of safety and repose for this state . . . For the general difference among our good subjects, and the particular evils of the soundest parts of the state, we judged might be easily cured, after the principal cause (the continuation of civil war) was taken away. In which having, by the blessing of God, well and happily succeeded, all hostility and wars through the kingdom being now ceased, we hope that we will succeed equally well in other matters remaining to be settled, and that by this means we shall arrive at the establishment of a good peace, with tranquility and rest. . . . Among our said affairs . . . one of the principal has been the complaints we have received from many of our Catholic provinces and cities, that the exercise of the Catholic religion was not universally re-established, as is provided by edicts or statutes heretofore made for the pacification of the troubles arising from religion; as well as the supplications and remonstrances which have been made to us by our subjects of the Reformed religion, regarding both the non-fulfillment of what has been granted by the said former laws, and that which they desired to be added for the exercise of their religion, the liberty of their consciences and the security of their persons and fortunes; presuming to have just reasons for desiring some enlargement of articles, as not being without great apprehensions, because their ruin has been the principal pretext and original foundation of the late wars, troubles, and commotions. Now not to burden us with too much business at once, as also that the fury of war was not compatible with the establishment of laws, however good they might be, we have hitherto deferred from time to time giving remedy herein. But now that it has pleased God to give us a beginning of enjoying some rest, we think we cannot employ ourself better than to apply to that which may tend to the glory and service of His holy name, and to provide that He may be adored and prayed unto by all our subjects: and if it has not yet pleased Him to permit it to be in one and the same form of religion, that it may at the least be with one and the same intention, and with such rules that may prevent among them all troubles and tumults. . . . For this cause, we have upon the whole judged it necessary to give to all our said subjects one general law, clear, pure, and absolute, by which they shall be regulated in all differences which have heretofore risen among them, or may hereafter rise, wherewith the one and other may be contented, being framed according as the time requires: and having had no other regard in this deliberation than solely the zeal we have to the service of God, praying that He would from this time forward render to all our subjects a durable and established peace. . . . We have by this edict or statute perpetual and irrevocable said, declared, and ordained, saying, declaring, and ordaining;

That the memory of all things passed on the one part and the other, since the beginning of the month of March 1585 until our coming to the crown, and also during the other preceding troubles, and the occasion of the same, shall remain extinguished and suppressed, as things that had never been. . . .

We prohibit to all our subjects of whatever state and condition they be, to renew the memory thereof, to attack, resent, injure, or provoke one another by reproaches for what is past, under any pretext or cause whatsoever, by disputing, contesting, quarrelling, reviling, or offending by factious words; but to contain themselves, and live peaceably together as brethren, friends, and fellow-citizens, upon penalty for acting to the contrary, to be punished for breakers of peace, and disturbers of the public quiet.

We ordain, that the Catholic religion shall be restored and re-established in all places, and quarters of this kingdom and country under our obedience, and where the exercise of the same has been interrupted, to be there again, peaceably and freely exercised without any trouble or impediment. . . .

And not to leave any occasion of trouble and difference among our subjects, we have permitted and do permit to those of the Reformed religion, to live and dwell in all the cities and places of this our kingdom and countries under our obedience, without being inquired after, vexed, molested, or compelled to do any thing in religion, contrary to their conscience. . . .

We permit also to those of the said religion to hold, and continue the exercise of the same in all the cities and places under our obedience, where it was by them established and made public at several different times, in the year 1586, and in 1597.

In like manner the said exercise may be established, and re-established in all the cities and places where it has been established or ought to be by the Statute of Pacification, made in the year 1577 . . .

We prohibit most expressly to all those of the said religion, to hold any exercise of it . . . except in places permitted and granted in the present edict. As also not to exercise the said religion in our court, nor in our territories and countries beyond the mountains, nor in our city of Paris, nor within five leagues of the said city. . . .

We prohibit all preachers, readers, and others who speak in public, to use any words, discourse, or propositions tending to excite the people to sedition; and we enjoin them to contain and comport themselves modestly, and to say nothing which shall not be for the instruction and edification of the listeners, and maintaining the peace and tranquility established by us in our said kingdom. . . .

They [French Protestants] shall also be obliged to keep and observe the festivals of the Catholic Church, and shall not on the same days work, sell, or keep open shop, nor likewise the artisans shall not work out of their shops, in their chambers or houses privately on the said festivals, and other days forbidden, of any trade, the noise whereof may be heard outside by those that pass by, or by the neighbors. . . .

We ordain, that there shall not be made any difference or distinction upon the account of the said religion, in receiving scholars to be instructed in the universities, colleges, or schools, nor of the sick or poor into hospitals, sick houses or public almshouses. . . .

We will and ordain, that all those of the Reformed religion, and others who have followed their party, of whatever state, quality or condition they be, shall be obliged and constrained by all due and reasonable ways, and under the penalties contained in the said edict or statute relating thereunto, to pay tithes to the curates, and other ecclesiastics, and to all others to whom they shall appertain. . . .

To the end to re-unite so much the better the minds and good will of our subjects, as is our intention, and to take away all complaints for the future; we declare all those who make or shall make profession of the said Reformed religion, to be capable of holding and exercising all estates, dignities, offices, and public charges whatsoever. . . .

We declare all sentences, judgments, procedures, seizures, sales, and decrees made and given against those of the Reformed religion, as well living as dead, from the death of the deceased King Henry the Second our most honored Lord and father in law, upon the occasion of the said religion, tumults and troubles since happening, as also the execution of the same judgments and decrees, from henceforward canceled, revoked, and annulled. . . .

Those also of the said religion shall depart and desist henceforward from all practices, negotiations, and intelligences, as well within or without our kingdom; and the said assemblies and councils established within the provinces, shall readily separate, and also all the leagues and associations made or to be made under any pretext, to the prejudice of our present edict, shall be cancelled and annulled, . . . prohibiting most expressly to all our subjects to make henceforth any assessments or levies of money, fortifications, enrollments of men, congregations and assemblies of other than such as are permitted by our present edict, and without arms. . . .

We give in command to the people of our said courts of parlement, chambers of our courts, and courts of our aids, bailiffs, chief-justices, provosts and other of our justices and officers to whom it appertains, and to their lieutenants, that they cause to be read, published, and registered this present edict and ordinance in their courts and jurisdictions, and the same keep punctually, and the contents of the same to cause to be enjoined and used fully and peaceably to all those to whom it shall belong, ceasing and making to cease all troubles and obstructions to the contrary, for such is our pleasure: and in witness hereof we have signed these presents with our own hand; and to the end to make it a thing firm and stable for ever, we have caused to put and endorse our seal to the same. Given at Nantes in the month of April in the year of Grace 1598, and of our reign the ninth.

Signed

HENRY

1. Who wrote this document, when, and where?

Many documents will not answer these questions directly; therefore, you will have to look elsewhere for clues. In this case, however, the internal evidence is clear. The author is Henry IV, king of France and Navarre, who issued the document in the French town of Nantes in 1598. Aside from the appearance of his name in the edict, there are other, less explicit, markers of his identity. He uses the first person plural (“we”) when referring to himself, a grammatical choice that both signals and accentuates his royal stature.

2. What type of document is this?

In this source, you do not have to look far for an answer to this question. Henry IV describes the document as an “edict,” “statute,” or “law.” These words reveal the public and official nature of the document, echoing their use in our own society today. Even if you do not know exactly what an edict, statute, or law meant in late-sixteenth-century terms, the document itself points the way: “we [Henry IV] have upon the whole, judged it necessary to give to all our subjects one general law, clear, pure, and absolute. . . .” Now you know that the document is a body of law issued by King Henry IV in 1598, which helps to explain its formality as well as the predominance of legal language.

3. Who is the intended audience of the document?

The formal and legalistic language of the edict suggests that Henry IV’s immediate audience is not the general public but rather some form of political and/or legal body. The final paragraph supports this conclusion. Here Henry IV commands the “people of our said courts of parlement, chambers of our courts, and courts of our aids, bailiffs, chief-justices, provosts, and other of our justices and officers . . .” to read and publish the edict. Reading between the lines, you can detect a mixture of power and dependency in Henry IV’s tone. Look carefully at his verb choices throughout the edict: prohibit, ordain, will, declare, command. Each of these verbs casts Henry IV as the leader and the audience as his followers. This strategy was essential because the edict would be nothing but empty words without the courts’ compliance. Imagine for a moment that Henry IV was not the king of France but rather a soldier writing a letter to his wife or a merchant preparing a contract. In either case, the language chosen would have changed to suit the genre and audience. Thus, identifying the relationship between author and audience can help you to understand both what the document does and does not say.

4. What are the main points of this document?

To answer this question, you should start with the preamble, for it explains why the edict was issued in the first place: to replace the “frightful troubles, confusions, and disorders” in France with “one general law . . . by which they [our subjects] might be regulated in all differences which have heretofore risen among them, or may hereafter rise. . . .” But what differences specifically? Even with no knowledge of the circumstances surrounding the formulation of the edict, you should notice the numerous references to “the Catholic religion” and “the Reformed religion.” With this in mind, read the preamble again. Here we learn that Henry IV had received complaints from Catholic provinces and cities and from Protestants (“our subjects of the Reformed religion”) regarding the exercise of their respective religions. Furthermore, as the text continues, since “it has pleased God to give us a beginning of enjoying some rest, we think we cannot employ ourself better than to apply to that which may tend to the glory and service of His holy name, and to provide that He may be adored and prayed unto by all our said subjects, and if it has not yet pleased Him to permit it to be in one and the same form of religion, that it may be at the least with one and the same intention, and with such rules that may prevent among them all troubles and tumults. . . .” Now the details of the document fall into place. Each of the articles addresses specific “rules” governing the legal rights and obligations of French Catholics and Protestants, ranging from where they can worship to where they can work.

5. Why was this document written?

As we have already seen, Henry IV relied on the written word to convey information and, at the same time, to express his “power” and “strength.” The legalistic and formal nature of the edict aided him in this effort. Yet as Henry IV knew all too well, the gap between law and action could be large indeed. Thus Henry IV compiled the edict not simply to tell people what to do but to persuade them to do it by delineating the terms of religious coexistence point by point and presenting them as the best safeguard against the return of confusion and disorder. He thereby hoped to restore peace to a country that had been divided by civil war for the previous thirty-six years.

6. What does this document reveal about the particular society and period in question?

Historians have mined the Edict of Nantes for insight into various facets of Henry IV’s reign and Protestant-Catholic relations at the time. Do not be daunted by such complexity; you should focus instead on what you see as particularly predominant and revealing themes. One of the most striking in the Edict of Nantes is the central place of religion in late-sixteenth-century society. Our contemporary notion of the separation of church and state had no place in the world of Henry IV and his subjects. As he proclaims in the opening lines, he was king “by the Grace of God” who had given him “virtue” and “strength.” Furthermore, you might stop to consider why religious differences were the subject of royal legislation in the first place. Note Henry IV’s statement that “if it has not yet pleased Him [God] to permit [Christian worship in France] to be in one and the same form of religion, that it may at the least be with one and the same intention. . . .” What does this suggest about sixteenth-century attitudes toward religious difference and tolerance? You cannot answer this question simply by reading the document in black-and-white terms; you need to look beyond the words and between the lines to draw out the document’s broader meanings.

Interpreting Visual Sources

Historians do not rely on written records alone to reconstruct the past; they also turn to nonwritten sources, which are equally varied and rich. By drawing on archeological evidence, historians have reconstructed the material dimensions of everyday life in centuries long past; others have used church sculpture to explore popular religious beliefs; and the list continues. This book includes a range of visual representations to enliven your view of history while enhancing your interpretive skills. Interpreting a visual document is very much like interpreting a nonvisual one—you begin with six questions similar to the ones you have already applied to the Edict of Nantes and move from ascertaining the “facts” of the document to a more complex analysis of the visual document’s historical meanings and value.

1. Who created this image, when and where?

Just as with written sources, identifying the artist or creator of an image, and when and where it was produced will provide a foundation for your interpretation. Some visual sources, such as a painting or political cartoon signed by the artist, are more forthcoming in this regard. But if the artist is not known (and even if he or she is), there are other paths of inquiry to pursue. Did someone commission the production of the image? What was the historical context in which the image was produced? Piecing together what you know on these two fronts will allow you to draw some basic conclusions about the image.

2. What type of image is this?

The nature of a visual source shapes its form and content because every visual genre has its own conventions. Take a map as an example. At the most basic level, maps are composites of images created to convey topographical and geographical information about a particular place, whether a town, a region, or a continent. Think about how you use maps in your own life. Sometimes they can be fanciful in their designs but typically they have a practical function—to enable the viewer to get from one place to another or at the very least to get a sense of an area’s spatial characteristics. A formal portrait, by contrast, would conform to a different set of conventions and, of equal significance, a different set of viewer expectations and uses.

3. Who are the intended viewers of the image?

As with written sources, identifying the relationship between the image’s creator and audience is essential to illuminate fully what the artist is trying to convey. Was the image intended for the general public, such as a photograph published in a newspaper? Or was the intended audience more private? Whether public, private, or somewhere in between, the creator’s target audience shapes his or her choice of subject matter, format, and style, which in turn should shape your interpretation of its meaning and significance.

4. What is the central message of the image?

Images convey messages just as powerfully as the written word. The challenge is to learn how to “read” pictorial representations accurately. Since artists use images, color, and space to communicate with their audiences, you must train your eyes to look for visual rather than verbal cues. A good place to start is to note the image’s main features, followed by a closer examination of its specific details and their interrelationship.

5. Why was this image produced?

Images are produced for a range of reasons—to convey information, to entertain, or to persuade, to name just a few. Understanding the motivations underlying an image’s creation is key to unraveling its meaning (or at least what it was supposed to mean) to people at the time. For example, the impressionist painters of the nineteenth century did not paint simply to paint—their style and subject matter intentionally challenged contemporary artistic norms and conventions. Without knowing this, you cannot appreciate the broader context and impact of impressionist art.

6. What does this image reveal about the society and time period in which it was created?

Answering the first five questions will guide your answer here. Identifying the artist, the type of image, and when, where, and for whom it was produced allows you to step beyond a literal reading of the image into the historical setting in which it was produced. Although the meaning of an image can transcend its historical context, its point of origin and intended audience cannot. Therein rests an image’s broader value as a window onto the past, for it is a product of human activity in a specific time and place, just like written documents.

Guided by these six questions, you can evaluate visual sources on their own terms and analyze the ways in which they speak to the broader historical context. Once again, let’s take an example.

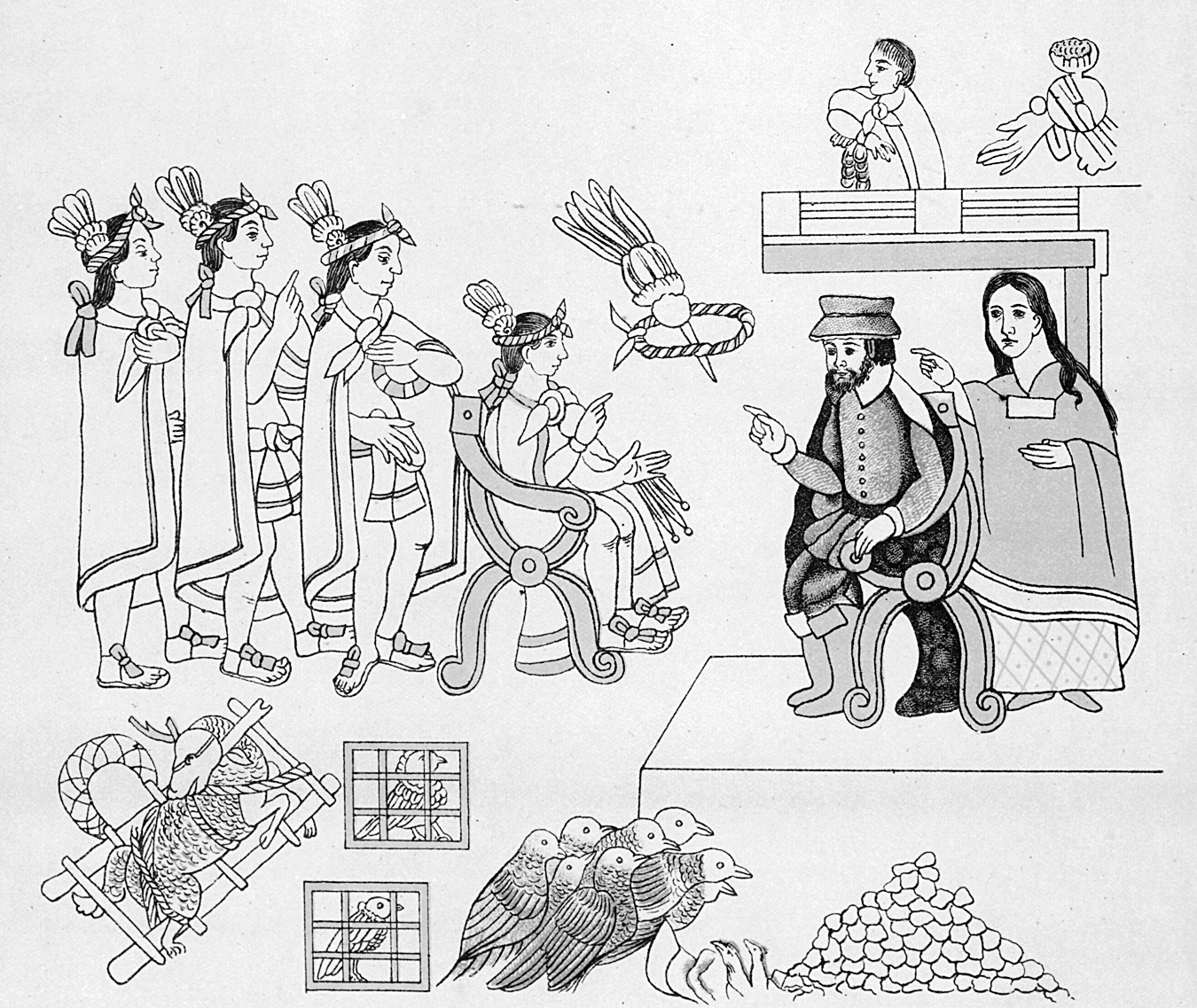

Lienzo de Tlaxcala (c. 1560)

Like Bernal Díaz del Castillo, the peoples of central Mexico had a stake in recording the momentous events unfolding around them, for they had long believed that remembering the past was essential to their cultural survival. Traditionally, local peoples used pictoriographic representations to record legends, myths, and historical events. After the Spaniards’ arrival, indigenous artists borrowed from this tradition to produce their own accounts of the conquest, including the image on page 11. It is one of a series contained in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, painted on cloth in the mid-sixteenth century. Apparently, the Lienzo was created for the Spanish viceroy to commemorate the alliance of the Tlaxcalans with the Spaniards. The Tlaxcalans were enemies of the Aztecs and after initial resistance to the Spanish invasion decided to join their forces. This particular image depicts two related events. The first is the meeting between the Aztec leader Moctezuma and Hernán Cortés in Tenochtitlán in August 1519. Cortés is accompanied by Doña Marina, his translator and cultural mediator; Moctezuma appears with warriors at his side. Rather than showing Moctezuma in his traditional garb, the artist dressed him in the manner of the Tlaxcalans. Both sit in European-style chairs, a nod to European artistic influence, and a Tlaxcalan headdress is suspended in the air between them. Game and fowl offered to the Spaniards are portrayed at the bottom. Within a week of this meeting, Cortés imprisoned Moctezuma in his own palaces with the Tlaxcalans’ help. Moctezuma the prisoner appears in the upper right of the image as an old, weak ruler whose sun has set.

1. Who created this image, when and where?

In this case, you will have to rely on the headnote to answer these questions. The image was created by an unknown Tlaxcalan artist in the mid-sixteenth century as part of a pictorial series, the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, depicting the Spanish conquest of Aztec Mexico. Although the image commemorates events that took place in 1519, it was produced decades later, when Spanish imperial control was firmly entrenched. Thus the image represents a visual point of contact between Spanish and indigenous traditions in the age of European global expansion. Although knowing the identity of the artist would be ideal, the fact that he was Tlaxcalan is of greater value. The Tlaxcalans had allied themselves with the Spanish and considered the Lienzo a way of highlighting their role in the Aztecs’ defeat.

2. What type of image is this?

On the one hand, this image fits into a long pictorial tradition among the peoples of central Mexico. Before the conquest, they had no alphabetic script. Instead, they drew on a rich repertoire of images and symbols to preserve legends, myths, and historical events. These images and symbols, which included the stylized warriors shown here, were typically painted into books made of deerskin or a plant-based paper. On the other hand, the image also reveals clear European influences, most noticeably in the type of chair in which both Cortés and Moctezuma sit. Looking at the image again with these dual influences in mind, think about how the pictorial markers allowed both indigenous and Spanish viewers to see something recognizable in an event that marked the destruction of one world and the creation of another.

3. Who are the intended viewers of the image?

As the headnote reveals, the image’s creator had a specific audience in mind, a Spanish colonial administrator. You should take this fact into account as you think about the image’s meaning and significance. Just because a Tlaxcalan artist created the image does not necessarily mean that it represents an unadulterated native point of view. And just because the image documents two historical events does not necessarily mean that the “facts” are objectively presented.

4. What is the central message of the image?

There are many visual components of this image, each of which you should consider individually and then as part of the picture as a whole. As you already know, the artist combined indigenous and European representational traditions. What does this suggest about the image’s message? The merging of these two traditions represents the alliance the Tlaxcalans forged with the Spanish. Looking closer, think about how the two leaders, Cortés and Moctezuma, are represented. Cortés is accompanied by his translator, Doña Marina, a Nahua woman. Originally a slave, she had been given to Cortés after his defeat of the Maya at Potonchan. She became a crucial interpreter and cultural mediator for Cortés in the world of the Mexica. Language appears here as a source of his power as well as his alliance with the Tlaxcalans. Although the Spanish contingent was relatively small, thousands of Tlaxcalan and other native warriors entered Tenochtitlán with them, a show of force not lost on local residents. The artist captures this fact by clothing Moctezuma in Tlaxcalan dress—he had once ruled over them but now he was to be ruled. Soon after this meeting, Moctezuma was imprisoned in his own palaces. The artist captures this event in the upper right where Moctezuma is shown as a prisoner.

5. Why was this image produced?

Examining this image reveals the complexity of this question, regardless of the nature of the source. At first glance, the answer is easy: the image was created to commemorate specific events. Yet given what you know about the setting in which the image was produced, the “why” takes on a deeper meaning. The image does not simply record events; it sets a scene in which multiple meanings are embedded—the chairs, Doña Marina, the warriors—that suggest how the Spanish conquest transformed native culture. The image thus served a dual function—to inform the Spanish of the Tlaxcalans’ role in the conquest while affirming Spanish dominance over them.

6. What does this image reveal about the society and time period in which it was created?

Answering this question requires you to step beyond a literal meaning of the image into the historical setting in which it was produced. Here you will uncover multiple layers of the image’s broader significance. Consider the artist, for example, and his audience. What does the fact that a native artist created the image for a Spanish audience suggest about the nature of Spanish colonization? Clearly, the Spaniards did not make their presence felt as a colonial power simply by seizing land and treasure; they also reshaped indigenous people’s understanding of themselves in both the past and present. That the Tlaxcalans expressed this understanding visually in a historical document lent an air of permanence and legitimacy to Spanish colonization and, equally important, to the Tlaxcalans’ contributions to it.

Conclusion

Through your analysis of historical sources, you will not only learn details about the world in which the sources were created but also become an active contributor to our understanding of these details’ broader significance. Written documents and pictorial representations don’t just “tell” historians what happened; they require historians to step into their own imaginations as they strive to reconstitute the past. In this regard, historians’ approach to primary sources is exactly that which is described here. They determine the basics of the source—who created it, when, and where—as a springboard for increasingly complex levels of analysis. Each level builds upon the other, just like rungs on a ladder. If you take the time to climb each rung in sequence, you will be able to master the content of a source and to use it to bring history to life. The written and visual primary sources included in Sources of The Making of the West, Fourth Edition, will allow you to participate firsthand in the process of historical inquiry by exploring the people, places, and sights of the past and how they shaped their own world and continue to shape ours today.