From the Unification of Egypt to the Old Kingdom, 3050–2190 B.C.E.

From the Unification of Egypt to the Old Kingdom, 3050–2190 B.C.E.

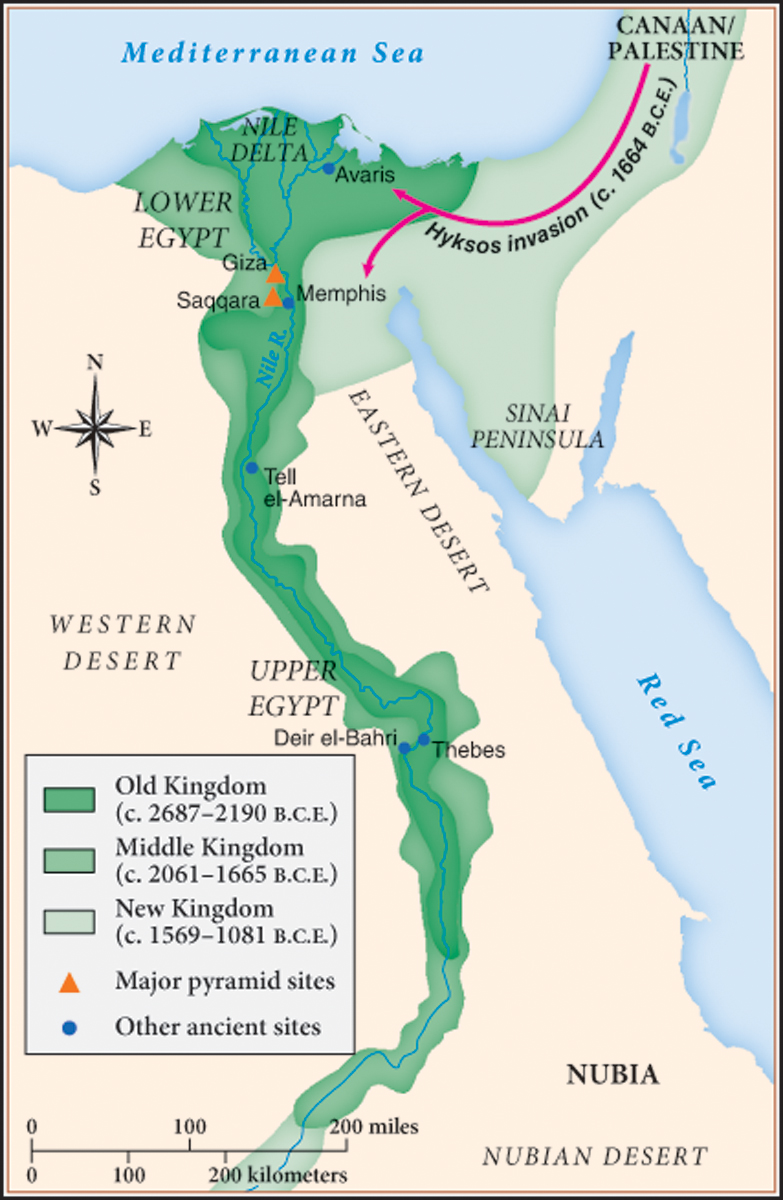

When climate change dried up the grasslands of the Sahara region of Africa about 5000–4000 B.C.E., people slowly migrated from there to the northeast corner of the continent, settling along the Nile River. Recent radiocarbon dating of skeletons, hair, and plants has confirmed that Egypt became a united political state by about 3050 B.C.E., when King Narmer (also called Menes)* united the previously separate territories of Upper (southern) and Lower (northern) Egypt. (Upper and Lower refer to the direction of the Nile River, which begins south of Egypt and flows northward to the Mediterranean.) The Egyptian ruler therefore referred to himself as King of the Two Lands. By around 2687 B.C.E., its monarchs had created a large centralized state, called the Old Kingdom. It lasted until around 2190 B.C.E. (Map 1.2). Egyptian kings built only a few large cities. The first capital, Memphis (south of modern Cairo), grew into a metropolis packed with mammoth structures.

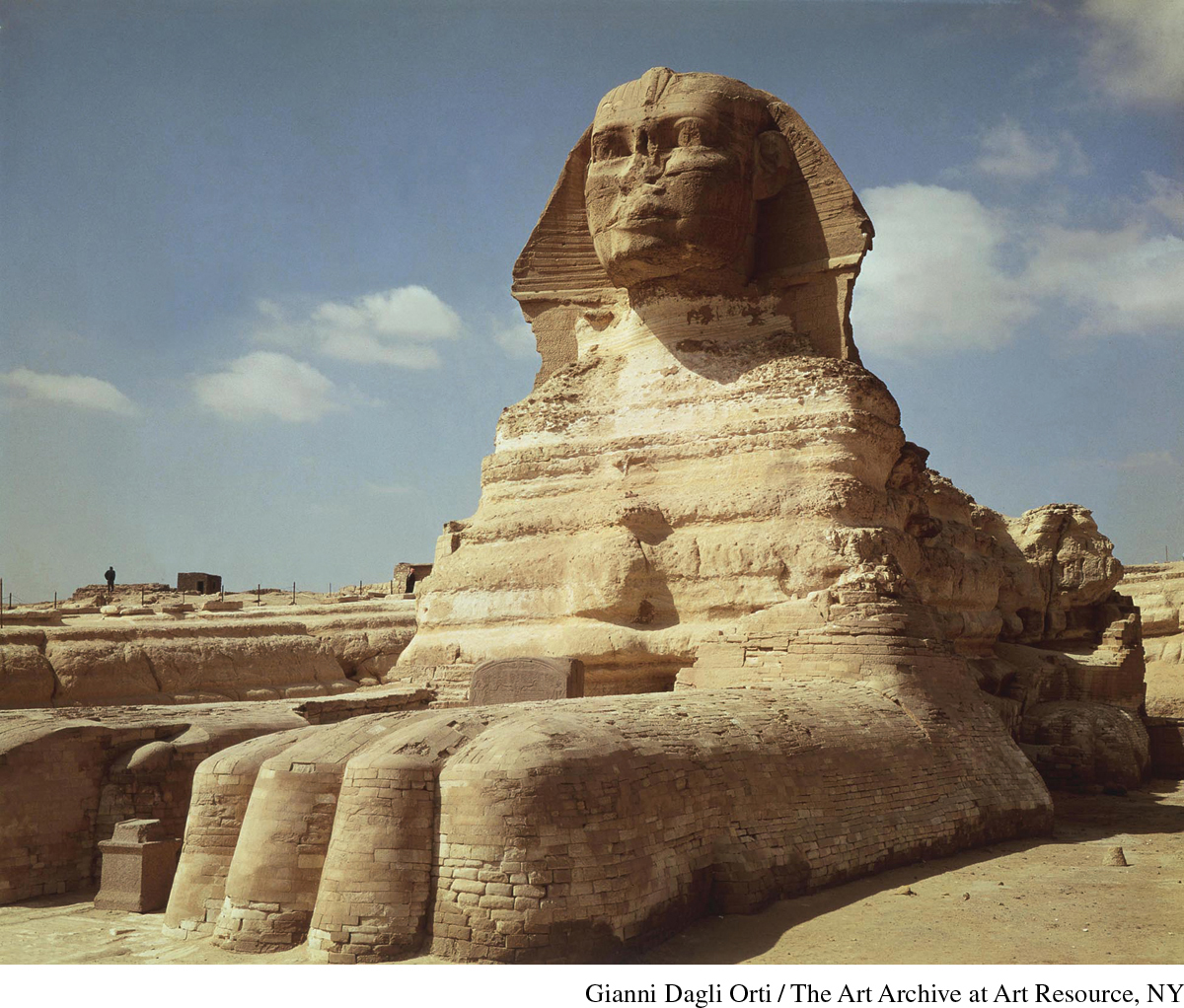

The most spectacular—and most mysterious—of the Old Kingdom architectural marvels is the so-called Great Sphinx. The world’s oldest monumental sculpture, this stone statue has a human head on the body of a lion lying on its four paws. It is nearly 250 feet long and almost 70 feet high. A temple was built in front of it, perhaps to worship the sun as a god. The Sphinx’s purpose and date remain hotly debated. No records exist to explain its original meaning. Most scholars believe that it was erected sometime in the Old Kingdom. A few, however, citing its weathering and erosion patterns, argue that it is as old as 5000 B.C.E. If clear evidence supporting this date is ever discovered, then the history of early Egypt will have to be completely rewritten. This is just one of the many controversies about ancient Egypt that archaeology may someday settle.

The Old Kingdom’s costly architecture demonstrates the prosperity and power of Narmer’s unified state. Its territory consisted of a narrow strip of fertile land running along both sides of the Nile River. This ribbon of green fields zigzagged for seven hundred miles southward from the Mediterranean Sea. The deserts flanking the fields on the west and the east protected Egypt; invasion was possible only through the northern Nile delta and from Nubia in the south. The deserts also were sources of wealth because they contained large deposits of metal ores. Egypt’s geography also contributed to its prosperity by supporting seaborne commerce in the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, as well as overland trade with central Africa.

Agriculture was Egypt’s most important economic resource. Usually, the Nile River overflowed its channel for several weeks each year, when melting snow from central African mountains swelled its waters. This predictable annual flood enriched the soil with nutrients from the river’s silt and diluted harmful mineral salts, thereby making farming more productive and supporting strong population growth. Unlike the unpredictable floods that harmed Mesopotamia, the regular flooding of the Nile benefited Egyptians. Trouble came in Egypt only if the usual flood did not take place, as happened when too little winter precipitation fell in the mountains.

The plants and animals raised by Egypt’s farmers fed a fast-growing population. Egypt had expanded to perhaps several million people by around 1500 B.C.E. Date palms, vegetables, grass for pasturing animals, and grain grew in abundance. The Egyptians loved beer, which people of all ages consumed. Thicker and more nutritious than modern brews, Egyptian beer was such an important food that it could be used to pay workmen’s wages. Egyptians, like other ancient societies, often flavored their beer with fruits.

Egypt’s population included people whose skin color ranged from light to dark. Although many ancient Egyptians would be regarded as black by modern racial classification, ancient peoples did not observe such distinctions. The modern controversy over whether Egyptians were people of color is therefore not an issue that ancient Egyptians would have considered. If asked, they would probably have identified themselves by geography, language, religion, or traditions rather than skin color. Like many other ancient groups, the Egyptians called themselves simply The People. Later peoples, especially the Greeks, recognized the ethnic and cultural differences between themselves and the Egyptians, but they deeply admired Egyptian civilization for its long history and strongly religious character.

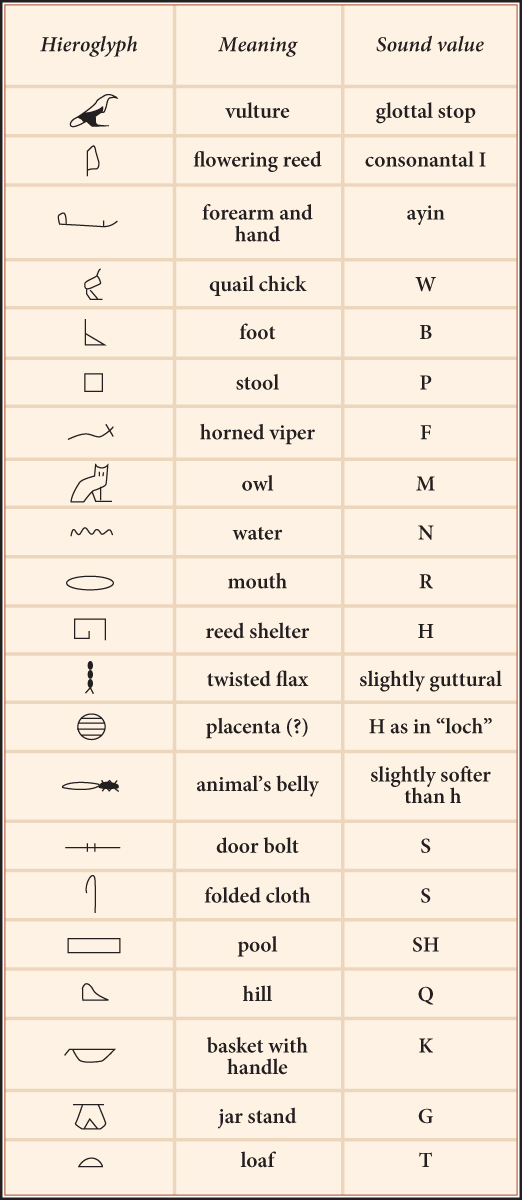

Although Egyptians absorbed knowledge from both the Mesopotamians and the Nubians, their African neighbors to the south, they developed their own written scripts. For official documents they used a pictographic script known as hieroglyphic (Figure 1.2). They developed other, simpler scripts for everyday purposes.

Some scholars believe that Nubian society was the outside influence that most deeply affected early Egypt. A Nubian social elite lived in dwellings much grander than the small huts housing most of the population. Egyptians interacted with Nubians while trading for raw materials such as gold, ivory, and animal skins, and Nubia’s hierarchical political and social organization possibly influenced the development of Egypt’s politically centralized Old Kingdom. Eventually, however, Egypt’s greater power led it to dominate its southern neighbor.

Keeping Egypt unified and stable was difficult. When the kings were strong, as during the Old Kingdom, the country was peaceful, with flourishing international trade. Regional governors rebelling against weak kings, however, could create political turmoil. Kings gained strength by fulfilling their public religious obligations. Egyptians worshipped a great variety of gods, often shown in paintings and sculptures as creatures with both human and animal features, such as the head of a jackal or a bird atop a human body. These images reflected the belief that the gods each had a particular animal through which they revealed themselves to human beings. Egyptian gods were associated with powerful natural objects, emotions, qualities, and technologies—examples are Re, the sun god; Isis, the goddess of love and fertility; and Thoth, the god of wisdom and the inventor of writing. People worshipped the gods with rituals, prayers, and festivals that expressed their respect and devotion to these divine powers.

Egyptians regarded their king as a helpful divinity in human form, identified with the hawk-headed god Horus. They saw the king’s rule as divine because he helped generate maat (“what is right”), the supernatural force that brought order and harmony to human beings if they maintained a stable hierarchy. The goddess Maat—the embodiment of the divine force of justice—therefore oversaw a society that the Egyptians believed would fall apart violently if the king ruled unjustly. The king therefore had the duties of pleasing the gods, making law, and waging war on enemies.

Art expressed the king’s legitimacy as ruler by representing him doing his religious and military duties. The requirement to show piety (proper religious belief and behavior) demanded strict regulation of the king’s daily activities: he had specific times to take a bath, go for a walk, and make love to his wife. Most important, he had to ensure the country’s fertility and prosperity. If the Nile flood failed to occur, this was seen as the king’s fault and weakened his authority by leaving many people hungry and angry, thus encouraging rebellions by rivals.

Successful Old Kingdom rulers used expensive building programs to demonstrate their piety and status. They erected huge tombs—the pyramids—in the desert outside Memphis. Temples and halls accompanied the tombs for religious ceremonies and royal funerals. Although the pyramids were not the first monuments built from enormous worked stones (the temples, admittedly enormously smaller in scale, on the Mediterranean island of Malta are earlier), they rank as the grandest, much larger even than the Great Sphinx.

Old Kingdom rulers spent vast resources on these giant complexes to proclaim their divine status and protect their mummified bodies for existence in the afterlife. King Khufu (r. 2609–2584 B.C.E.; also known as Cheops) commissioned the hugest monument of all—the Great Pyramid at Giza. Taller than a forty-story skyscraper at 480 feet high, it covered thirteen acres and stretched 760 feet long on each side. It required more than two million blocks of limestone, some of which weighed fifteen tons. Its exterior blocks were quarried along the Nile, floated down the river on barges, and pulled to the site on sleds over sand dampened to reduce friction. Free workers then dragged the blocks up ramps into position using rollers and wooden pads.

The Old Kingdom rulers’ expensive preparations for death reflected their belief in the afterlife. One text says: “O [god] Atum, put your arms around King Neferkare Pepy II [r. c. 2300–2206 B.C.E.], around this construction work, around this pyramid. . . . May you guard lest anything happen to him evilly throughout the course of eternity.” The royal family equipped their tombs with many comforts to use in the underworld. The kings had gilded furniture, sparkling jewelry, and precious objects placed alongside the coffins holding their mummies. Archaeologists have even uncovered two full-sized cedar ships buried next to the Great Pyramid, meant to carry King Khufu on his journey into eternity.

The Old Kingdom ranked Egyptians in a strict hierarchy to preserve their kings’ authority and support what they regarded as the proper order of a just society. Egyptians, believing their ordered society was superior to any other, despised foreigners. The king and queen headed the hierarchy. Brothers and sisters in the royal family could marry each other, perhaps because such matches were thought to preserve the purity of the royal line and imitate the gods’ marriages. The priests, royal administrators, provincial governors, and army commanders ranked second. Then came the free common people, most of whom worked in agriculture. Free workers had heavy obligations to the state. In a system called corvée labor, the kings commanded commoners to work on the pyramids during slack times in farming. The state fed, housed, and clothed the workers while they performed this seasonal work; their labor was a way of paying taxes. Taxation reached 20 percent on the farmers’ produce. Slaves captured in foreign wars served the royal family and the priests; privately owned slaves became numerous only after the Old Kingdom. The king hired mercenaries, many from Nubia, to form the majority of the army.

Egyptians preserved more of the gender equality of the early Stone Age than did their neighbors. Women generally enjoyed the same legal rights as free men. They could own land and slaves, inherit property, pursue lawsuits, transact business, and initiate divorces. Portrait statues show the equal status of wife and husband: each figure is the same size and sits on the same kind of chair. Men dominated public life, while women devoted themselves mainly to private life, managing their households and property. When their husbands went to war or were killed in battle, however, women often took on men’s work. Women could serve as priestesses, farm managers, or healers in times of crisis.

The formal style of Egyptian art illustrates the high value placed on order and predictability. Statues represent the subject either standing stiffly with the left leg advanced or sitting on a chair or throne, stable and poised. The concern for decorum (suitable behavior) also appears in the Old Kingdom literature called wisdom literature—texts giving instructions for appropriate behavior. One text instructs a young man to seek advice from ignorant people as well as the wise, and to avoid arrogant overconfidence. This kind of literature had a strong influence on later civilizations, especially the ancient Israelites.