The Emergence of Cities in Mesopotamia, 4000–2350 B.C.E.

The Emergence of Cities in Mesopotamia, 4000–2350 B.C.E.

Significant changes in human society took place when the first cities—and therefore the first civilization—emerged in Mesopotamia about 4000–3000 B.C.E. on the plains bordering the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (see Map 1.1, page 6). Cities developed there because the climate and the land could support large populations. (See “Taking Measure: The Rate of Population Growth to 1000 B.C.E.”) Mesopotamian farmers operated in a challenging environment: temperatures soared to 120 degrees Fahrenheit and little rain fell in the low-lying plains, yet the rivers flooded unpredictably. They maximized agricultural production by devising the technology and administrative arrangements necessary to irrigate the arid flatlands with water diverted from the rivers. A vast system of canals controlled flooding and turned the desert green with food crops. The need to construct and maintain a system of irrigation canals in turn led to the centralization of authority in Mesopotamian cities, which controlled the farmland and irrigation systems outside their fortified walls. This political arrangement—an urban center exercising control over the surrounding countryside—is called a city-state. Mesopotamian city-states were independent communities competing with each other for land and resources.

The people of Sumer (southern Mesopotamia) established the earliest city-states. Unlike other Mesopotamians, the Sumerians did not speak a Semitic language (the group of languages from which Hebrew and Arabic came); the origins of their language remain a mystery. By 3000 B.C.E., the Sumerians had created twelve independent city-states—including Uruk, Eridu, and Ur—which repeatedly battled each other for territory. By 2500 B.C.E., most of the cities had expanded to twenty thousand residents or more. The rooms in Sumerians’ mud-brick houses surrounded open courts. Large homes had a dozen rooms or more.

Agricultural surpluses and trade in commodities and manufactured goods made the Sumerian city-states prosperous. Their residents bartered grain, vegetable oil, woolens, and leather with one another, and they acquired metal, timber, and precious stones from foreign trade. The invention of the wheel for use on transport wagons around 3000 B.C.E. strengthened the Mesopotamian economy. Traders traveled as far as India, where the cities of Indus civilization emerged about 2500 B.C.E. Two groups dominated the Sumerian economy: religious officials controlled the temples, and ruling families controlled large farms and gangs of laborers. Some private households also became rich.

Increasingly rigid forms of hierarchy evolved in Sumerian society. Slaves, owned by temple officials and by individuals, had the lowest status. People were enslaved by being captured in war, being born to slaves, voluntarily selling themselves or their children (usually to escape starvation), or being sold by their creditors when they could not repay loans (debt slavery). Children whose parents dedicated them as slaves to the gods could rise to prominent positions in temple administration. In general, however, slaves existed in near-total dependence on other people and were excluded from normal social relations. They usually worked without pay and lacked almost all legal rights. Considered as property, they could be bought, sold, beaten, or even killed by their masters.

Slaves worked in domestic service, craft production, and farming, but historians dispute whether slaves or free laborers were more important to the economy. Free persons performed most government labor, paying their taxes with work rather than with money, which was measured in amounts of food or precious metal (currency was not invented until much later). Although some owners liberated slaves in their wills and others allowed slaves to keep enough earnings to purchase their freedom, most slaves had little chance of becoming free.

Hierarchy became so strong in Mesopotamian society that it led to monarchy—the political system that became the most widespread form of government in the ancient world. In a monarchy, the king was at the top of the hierarchy, like the ruler of the gods. His male descendants inherited his position. To display their exalted status, royal families lived in elaborate palaces that served as administrative centers and treasure houses. Archaeologists excavating royal graves in Ur have revealed the rulers’ dazzling riches—spectacular possessions crafted in gold, silver, and precious stones. These graves also have yielded grisly evidence of the top-ranking status of the king and queen: servants killed to care for their royal masters after death.

Patriarchy—domination by men in political, social, and economic life—already existed in Mesopotamian city-states, probably as an inheritance from the development of hierarchy in Paleolithic times. A Sumerian queen was respected because she was the king’s wife and the mother of the royal children, but her husband held supreme power. The king formed a council of older men as his advisers, but he publicly acknowledged the gods as his rulers; this concept made the state a theocracy (government by gods) and gave priests and priestesses public influence. The king’s greatest responsibility was to keep the gods happy and to defeat attacks from rival cities. The king collected taxes from the working population to support his family, court, palace, army, and officials. The kings, along with the priests of the large temples, regulated most of the economy in their kingdoms by controlling the exchange of food and goods between farmers and craft producers in a system known as a redistributive economy.

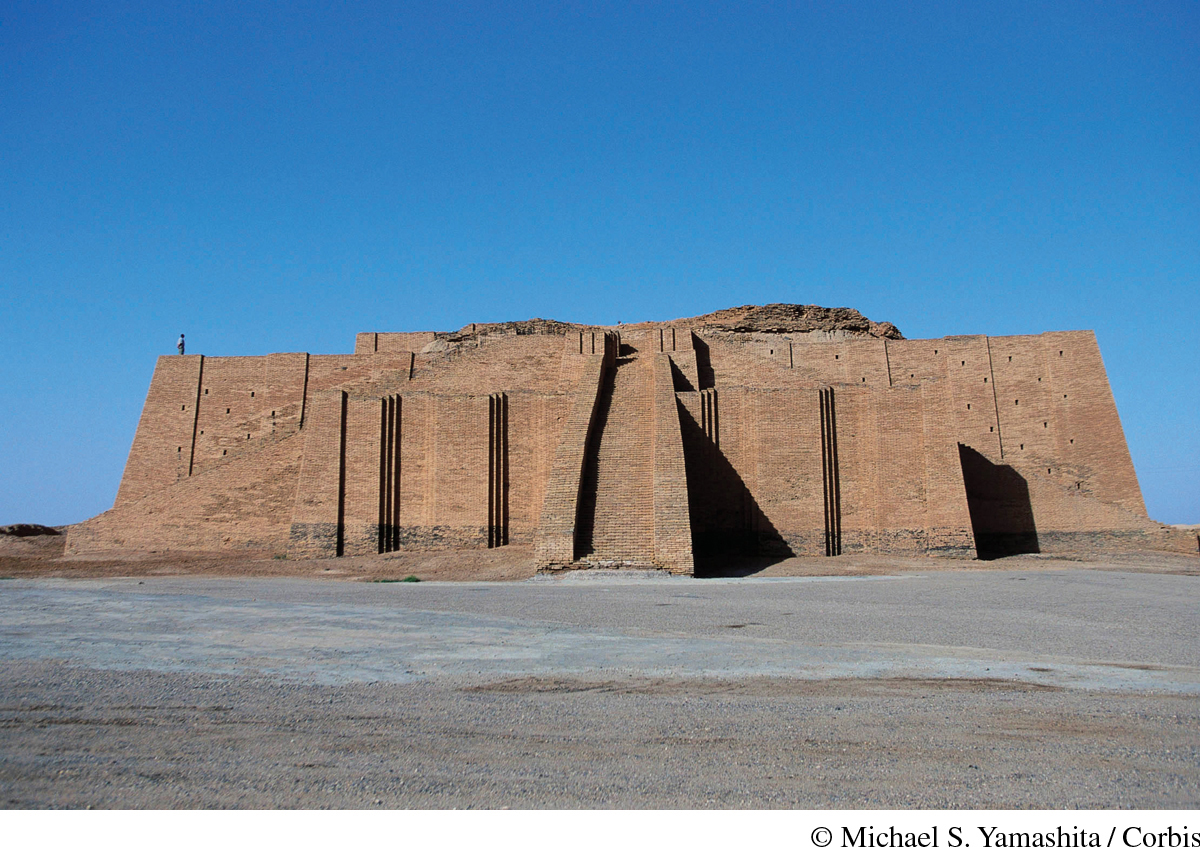

In religion, Mesopotamians continued earlier traditions by practicing polytheism: worshipping many gods thought to control different aspects of life, including the weather, fertility, and war. People believed that their safety depended on the goodwill of the gods, and each city-state honored a deity as its special protector. To please the gods, city dwellers offered sacrifices and built ziggurats (temple towers) soaring as high as ten stories. Mesopotamians believed that if human beings angered the gods, divinities such as the sky god, Enlil, and the goddess of love and war, Inanna (also called Ishtar), would punish them by sending disease, floods, famine, and defeats in war.

Myths told in long poems such as the Epic of Creation and the Epic of Gilgamesh expressed Mesopotamian ideas about the challenges and violence that human beings faced in struggling with the natural environment and creating civilization. Gilgamesh was a legendary king of Uruk who forced the young men of Uruk to labor like slaves and the young women to sleep with him. When his subjects begged the mother of the gods to grant them a protector, she created Enkidu, “hairy all over . . . dressed as cattle are.” A week of sex with a prostitute tamed this brute, preparing him for civilization: “Enkidu was weaker; he ran slower than before. But he had gained judgment, was wiser.” After wrestling to a draw, Gilgamesh and Enkidu became friends; together they defeated Humbaba (the ugly giant of the Pine Forest) and the Bull of Heaven. The gods doomed Enkidu to die soon after these triumphs. Depressed about the human condition and longing to cheat death, Gilgamesh sought the secret of immortality, but a thieving snake ruined his quest. He decided that the only immortality for mortals was winning fame for deeds. Only memory and gods could live forever. (See “Contrasting Views: The Gains and the Losses of Life in Civilization vs. Life in Nature.”)

Mesopotamian myths told in poetry, song, and art greatly influenced other peoples. A version of the Gilgamesh story recounted how the gods sent a huge flood over the earth. They warned one man, instructing him to build a boat. He loaded his vessel with his relatives, workers, and possessions; domesticated and wild animals; and “everything there was.” After a week of torrential rains, they left the boat to repopulate the earth and regenerate civilization. This story recalled the frequent floods of the Mesopotamian environment and was echoed later in the biblical account of the great flood covering the globe and Noah’s ark.

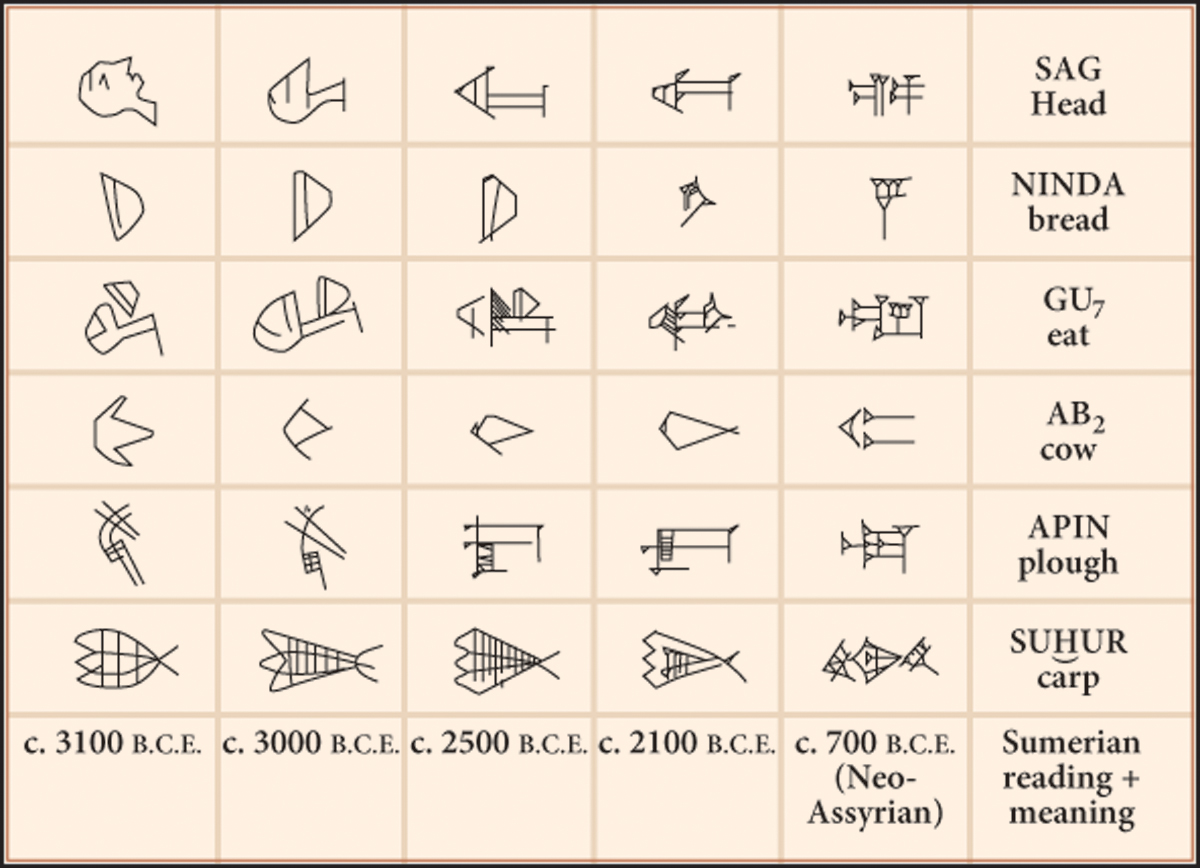

The invention of writing in Mesopotamia transformed the way people exchanged stories and ideas. Sumerians originally invented this new technology to do accounting. Before writing, people drew small pictures on clay tablets to keep count of objects or animals. Writing developed when people created symbols to represent the sounds of speech instead of pictures to represent concrete things. Sumerian writing did not use an alphabet (a system in which each symbol represents the sound of a letter), but rather a system of wedge-shaped marks pressed into clay tablets to represent the sounds of syllables and entire words (Figure 1.1). Today this form of writing is called cuneiform (from cuneus, Latin for “wedge”). For a long time, writing was a professional skill for accounting mastered by only a few men and women known as scribes.

The possibilities for communication over time and space exploded when people began writing down nature lore, mathematics, foreign languages, and literature. In the twenty-third century B.C.E., Enheduanna, the daughter of King Sargon of the city of Akkad, composed the oldest written poetry whose author is known. Written in Sumerian, her poetry praised the life-giving goddess of love, Inanna: “The great gods scattered from you like fluttering bats, unable to face your intimidating gaze . . . knowing and wise queen of all the lands, who makes all creatures and people multiply.” Later princesses who wrote love songs, lullabies, dirges, and prayers continued the Mesopotamian tradition of royal women becoming authors.