Metals and Empire Making: The Akkadians and the Ur III Dynasty, c. 2350–c. 2000 B.C.E.

Metals and Empire Making: The Akkadians and the Ur III Dynasty, c. 2350–c. 2000 B.C.E.

The riches for which people now fought had a new component: metal. Early metallurgy demonstrates how technological innovation can generate social and political change. Pure copper, which people had long been using, lost its shape and edge quickly. So craftsmen were motivated to invent ways to smelt ore and to make metal alloys at high temperatures. The invention of bronze, a copper-tin alloy hard enough to hold a razor edge, enabled metalsmiths to produce durable and deadly swords, daggers, and spearheads. The period from about 4000 to 1000 B.C.E. is called the Bronze Age because at this time bronze was the most important metal for weapons and tools; iron was not yet commonly used. The ownership of metal objects strengthened visible status divisions in society between men and women and rich and poor. This new technology allowed the Mesopotamian social elite to acquire new luxury goods in metal, improved tools for agriculture and construction, and bronze weapons. The desire to accumulate wealth and status symbols stimulated demand for decorated weapons and elaborate jewelry. Rich men ordered bronze swords and daggers with expensive inlays. Such weapons increased visible social differences between men and women because they marked the status of the masculine roles of hunter and warrior.

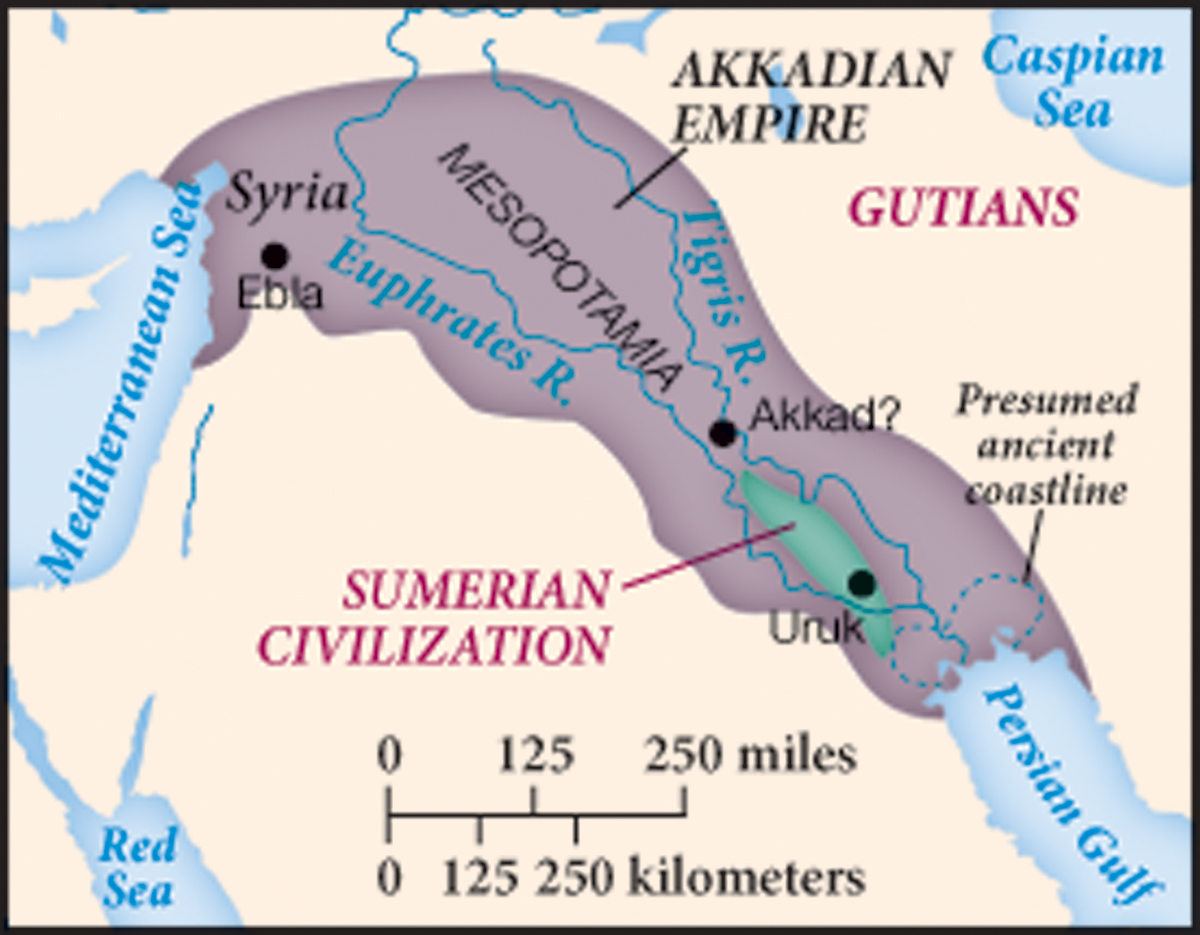

Mesopotamian rulers fought to capture territory containing ore mines. The desire to acquire metals led the kings of Akkad to create by force the world’s first empire (a political state in which a single power rules formerly independent peoples). It began around 2350 B.C.E., when Sargon, king of Akkad, launched invasions north and south of his central Mesopotamian homeland. He conquered Sumer and the regions all the way westward to the Mediterranean Sea, creating the Akkadian Empire. A poet of around 2000 B.C.E. credited Sargon’s success to the favor of the god Enlil: “To Sargon the king of Akkad, from below to above, Enlil had given him lordship and kingship.”

Sargon’s grandson Naram-Sin also conquered distant places to gain resources and glory. By around 2250 B.C.E., he had reached Ebla, a large city in Syria. Archaeologists have unearthed many cuneiform tablets at Ebla; these discoveries suggest that the city was a center for learning and trade.

The process of building an empire by force had the unintended consequence of spreading Mesopotamian literature and art and promoting cultural interaction. The Akkadians spoke a language unrelated to Sumerian, but in conquering Sumer they adopted much of that region’s religion, literature, and culture. Other peoples conquered by the Akkadians were then exposed to Sumerian beliefs and traditions, which they in turn adapted to suit their own purposes.

Civil war ended the Akkadian Empire. A newly resurgent Sumerian dynasty called Ur III (2112–2004 B.C.E.) seized power in Sumer. The Ur III rulers created a centralized economy, presided over a flourishing of Sumerian literature, published the earliest preserved law code, and justified their rule by proclaiming their king to be divine. The best-preserved ziggurat was built in their era. Royal hymns, a new literary form, glorified the king; one example reads: “Your commands, like the word of a god, cannot be reversed; your words, like rain pouring down from heaven, are without number.”

Mesopotamia remained politically unstable, however. When civil war weakened the Ur III kingdom, nearby Amorite marauders conducted damaging raids. The Ur III dynasty collapsed after only a century of rule.