The Values of the Olympic Games

The Values of the Olympic Games

Greece had recovered enough population and prosperity by the eighth century B.C.E. to begin creating new forms of social and political organization. The most vivid evidence is the founding of the Olympic Games, traditionally dated to 776 B.C.E. This international religious festival showcased the competitive value of aretê.

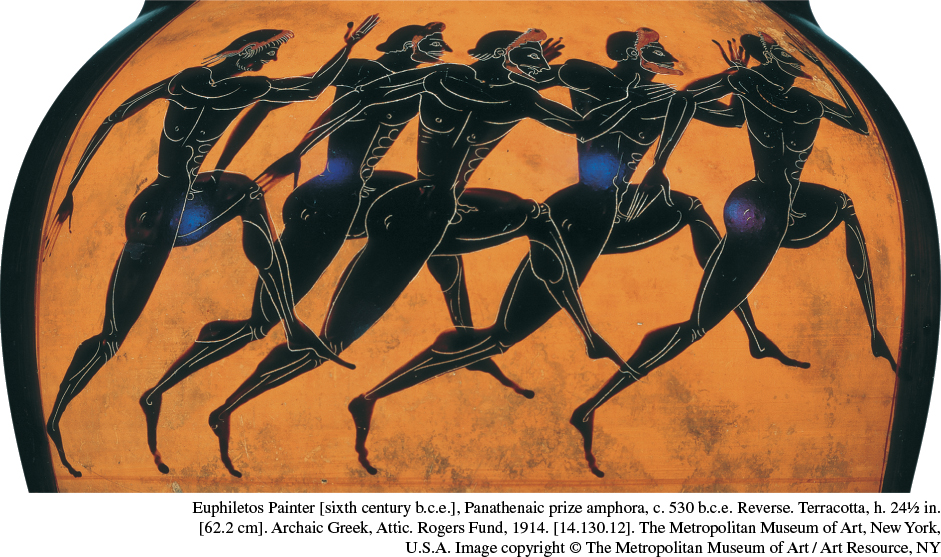

Every four years, the games took place in a huge sanctuary dedicated to Zeus, the king of the gods, at Olympia, in the northwestern Peloponnese. Male athletes from elite families vied in sports, imitating the aretê needed for war: running, wrestling, jumping, and throwing. Horse and chariot racing were added to the program later, but the main event remained a two-hundred-yard sprint, the stadion (hence our word stadium). The athletes competed as individuals, not on national teams. Winners received only a garland made from wild olive leaves to symbolize the prestige of victory.

The Olympics illustrate Greek notions of proper behavior for each gender: crowds of men flocked to the games, but women were prohibited on pain of death. Women had their own separate Olympic festival on a different date in honor of Hera, queen of the gods. Only unmarried women could compete. In later times, professional athletes dominated the Olympics, earning their living from appearance fees and prizes at games held throughout the Greek world.

Once every four years an international truce of several weeks was declared so that competitors and fans from all Greek communities could safely travel to and from Olympia. The games were open to any socially elite Greek male. These rules represented beginning steps toward a concept of collective Greek identity. The Olympics helped channel the competition for individual excellence into a new context of social cooperation and community values, essential preconditions for the creation of Greece’s new political form, the city-state ruled by citizens.