Citizenship and Freedom in the Greek City-State

Citizenship and Freedom in the Greek City-State

The creation of the polis filled the political vacuum left by Mycenaean civilization’s fall. The Greek city-state was unique because it was based on the concept of citizenship for all its free inhabitants, rejected monarchy as its central authority, and made justice the responsibility of the citizens. Moreover, except in tyrannies, in which one man seized control of the city-state, at least some degree of shared governing was normal.

Power sharing reached its widest form in democratic Greek city-states. The most famous ancient analyst of Greek politics and society, the philosopher Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.), argued, “Humans are beings who by nature live in a city-state.” Anyone who existed outside such a community, Aristotle remarked, must be either a simple fool or superhuman. The polis’s innovation in making shared power the basis of government did not immediately change the course of history—monarchy later became once again the most common form of government in ancient Western civilization—but it was important as proof that power sharing was a workable system of political organization.

Greek city-states were officially religious communities. As well as worshipping many deities, each city-state honored a particular god or goddess as its special protector, such as Athena at Athens. Different communities could choose the same deity: Sparta, Athens’s chief rival in later times, also chose Athena as its defender. Greeks envisioned the twelve most important gods banqueting atop Mount Olympus, the highest peak in mainland Greece. Zeus headed this pantheon; the others were Hera, his wife; Aphrodite, goddess of love; Apollo, sun god; Ares, war god; Artemis, moon goddess; Athena, goddess of wisdom and war; Demeter, earth goddess; Dionysus, god of pleasure, wine, and disorder; Hephaestus, fire god; Hermes, messenger god; and Poseidon, sea god. The Greeks believed that their gods occasionally experienced temporary pain or sadness but were immune to permanent suffering because they were immortal.

Greek religion’s core beliefs were that humans must honor the gods to thank them for blessings received and to receive more blessings in return, and that the gods sent both good and bad into the world. Gods could punish offenders by sending disasters such as floods, famines, earthquakes, epidemic diseases, and defeats in battle. The relationship between gods and humans generated sorrow as well as joy, and only a limited hope for favored treatment in this life and in the underworld after death even for the gods’ favorites. Ordinary Greeks did not expect the gods to take them to a paradise at some future time when evil forces would be eliminated forever. An inscription on a seventh-century B.C.E. bronze statuette sums up the reciprocity that characterized Greek religious ideas: “Mantiklos gave this from his share to [the god Apollo] the Far Darter of the Silver Bow; now you, Apollo, do something for me in return.”

Mythology hinted at the gods’ expectations of proper human behavior. For example, gods demanded hospitality for strangers and proper burial for family members. Other acts such as performing a sacrifice improperly, violating the sanctity of a temple area, or breaking an oath or sworn agreement counted as disrespect for the gods. Humans had to police most crimes themselves. Homicide was such a serious offense, however, that the gods were thought to punish it by casting a miasma (ritual contamination) on the murderer and on all those around. Unless the members of the affected group purified themselves by punishing the murderer, they could all expect to suffer divine punishment, such as bad harvests or disease.

Oracles, dreams, divination, and the interpretations of prophets provided clues about what humans might have done to anger the gods. The most important oracle was at Delphi, in central Greece, where a priestess in a trance provided Apollo’s answers—in the form of riddles that had to be interpreted—to questions posed by city-states as well as individuals.

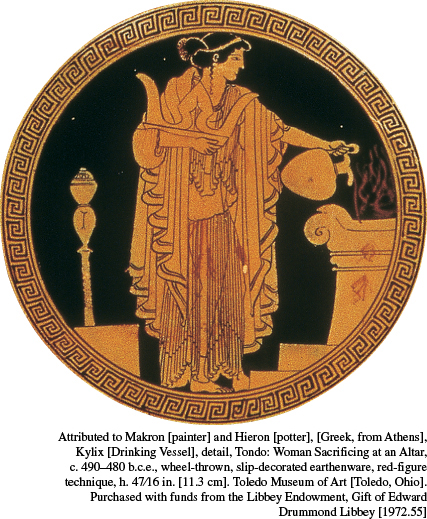

City-states honored gods by sacrificing animals such as cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs; decorating their sanctuaries with works of art; and celebrating festivals with songs, dances, prayers, and processions. Both city-states and individuals worshipped each god and goddess through a cult, a set of official, publicly funded religious activities overseen by priests and priestesses. People prayed, sang hymns of praise, offered sacrifices, and presented gifts at the deity’s sanctuary. In these holy places a person could honor and thank the deities for blessings and beg them for relief when misfortune struck the community or the individual. People could also offer sacrifices at home with the household gathered around; sometimes the family’s slaves were allowed to participate.

Priests and priestesses chosen from the citizen body performed the sacrifices of public cults; they did not use their positions to influence political or social matters. They were not guardians of correct religious thinking because Greek polytheism had no scripture or uniform set of beliefs and practices. It required its worshippers only to support the community’s local rituals and to avoid religious pollution.

The concept of citizenship in the Greek city-state meant free people agreeing to form a political community that was a partnership of privileges and duties in common affairs under the rule of law. (See “Document 2.2: Zaleucus’s Law Code for a Greek City-State in Seventh-Century B.C.E. Italy.”) Citizenship was a remarkable political concept because, even in Greek city-states organized as tyrannies or oligarchies (rule by a small group), it meant a basic level of political equality among citizens. Most important, it carried the expectation of equal treatment under the law for male citizens regardless of their social status or wealth. The degree of power sharing varied. In oligarchic city-states, small groups from the social elite or even a single family could dominate the process of legislating. Women had the protection of the law, but they were barred from participation in politics on the grounds that female judgment was inferior to male. Regulations governing sexual behavior and control of property were stricter for women than for men. (See “Taking Measure: Greek Family Size and Agricultural Labor in the Archaic Age.”)

In democratic city-states, all free adult male citizens shared in governing by attending and voting in a political assembly, where the laws and policies of the community were decided, and by serving on juries. Citizens did not enjoy perfect political equality. The right to hold office, for example, could be restricted to citizens possessing a certain amount of property. Equality prevailed most strongly in the justice system, in which all male citizens were treated the same, regardless of wealth or status. Making equality of male citizens the principle for the reorganization of Greek society and politics in the Archaic Age was a radical innovation. The polis—with its emphasis on equal protection of the laws for rich and poor alike—remained the preeminent form of political and social organization in Greece until the beginning of Roman control six centuries later.

How the poor originally gained the privileges of citizenship remains a mystery. The population increase in the late Dark Age and the Archaic Age was greatest among the poor. These families raised more children to help farm more land, which had been vacant after the depopulation brought on by the worst of the Dark Age. There was no precedent in Western civilization for extending even limited political and legal equality to the poor.

Historians have customarily believed that a hoplite revolution was the reason for expanded political rights. A hoplite was an infantryman who wore metal body armor and attacked with a thrusting spear. Hoplites formed the basis of the citizen militias that defended Greek city-states. Staying in line and working together were the secrets to successful hoplite tactics. In the eighth century B.C.E., a growing number of men became prosperous enough to buy metal weapons and train as hoplites, especially because the use of iron had made such weapons more readily available.

According to the hoplite revolution theory, these new hoplites—feeling that they should enjoy political rights in exchange for buying their own equipment and training hard—forced the social elite to share political power by threatening to refuse to fight, which would have crippled military defense. This interpretation correctly assumes that the hoplites had the power to demand and receive a voice in politics but ignores that hoplites were not poor. Furthermore, archaeology shows that not many men were wealthy enough to afford hoplite armor until the middle of the seventh century B.C.E., well after the earliest city-states had emerged. How then did poor men, too, win political rights?

The most likely explanation is that the poor earned respect by fighting to defend the community, just as hoplites did. Fighting as lightly armed troops, poor men could disrupt an enemy’s line by slinging rocks and shooting arrows. It is also possible that tyrants—sole rulers who seized power for their families in some city-states—boosted the status of poor men. Tyrants may have granted greater political rights to poor men as a means of gathering popular support.

The growth of freedom and equality for citizens in Greece produced a corresponding expansion of slavery, as free citizens protected their status by establishing clear distinctions between themselves and slaves. Many slaves were war captives. Pirates or raiders also seized people from non-Greek regions to sell into slavery. Rich families prized educated Greek-speaking slaves, who could tutor their children (no public schools existed yet).

City-states as well as individuals owned slaves. Publicly owned slaves enjoyed limited independence, living on their own and performing specialized tasks. In Athens, for example, special slaves were trained to detect counterfeit coinage. Temple slaves belonged to the deity of the sanctuary, for whom they worked as servants.

Slaves made up about one-third of the total population in some city-states by the fifth century B.C.E. They became cheap enough that even middle-class people could afford one or two. Still, small landowners and their families continued to do much work themselves. Not even wealthy Greek landowners acquired large numbers of agricultural slaves because maintaining gangs of hundreds of enslaved workers year-round was too expensive. Most crops required short periods of intense labor punctuated by long stretches of inactivity, and owners did not want to feed slaves who had no work.

Slaves did all kinds of jobs. Household slaves, often women, cleaned, cooked, fetched water from public fountains, helped the wife with the weaving, watched the children, accompanied the husband as he did the marketing, and performed other domestic chores. Neither female nor male slaves could refuse if their masters demanded sexual favors. Owners often labored alongside their slaves in small manufacturing businesses and on farms. Slaves toiling in the narrow, landslide-prone tunnels of Greece’s silver and gold mines had the most dangerous work.

Since slaves existed as property, not people, owners could legally beat or even kill them. But injuring or executing slaves made no economic sense—the master would have been damaging or destroying his own property. Under the best conditions, household workers could live free of violent punishment. They sometimes were allowed to join their owners’ families on excursions and attend religious rituals. However, without families of their own, without property, and without legal or political rights, slaves remained alienated from regular society. Sometimes owners freed their slaves, and some promised freedom at a future date to encourage their slaves to work hard. Those slaves who gained their freedom did not become citizens in Greek city-states but instead mixed into the population of noncitizens officially allowed to live in the community.

Greek slaves rarely rebelled on a large scale, except in Sparta, because they were usually of too many different origins and nationalities and too scattered to organize. No Greeks called for the abolition of slavery. The expansion of slavery in the Archaic Age reduced more and more people to a state of absolute dependence.

Although only free men had the right to participate in city-state politics and to vote, free women counted as citizens legally, socially, and religiously. Citizenship gave women security and status because it guaranteed them access to the justice system and a respected role in a cult. Free women had legal protection against being kidnapped for sale into slavery and access to the courts in disputes over property, although they usually had to have a man speak for them. The traditional paternalism of Greek society required that all women have male guardians to regulate their lives and safeguard their interests (as defined by men). Before a woman’s marriage, her father served as her legal guardian; after marriage, her husband took over that duty.

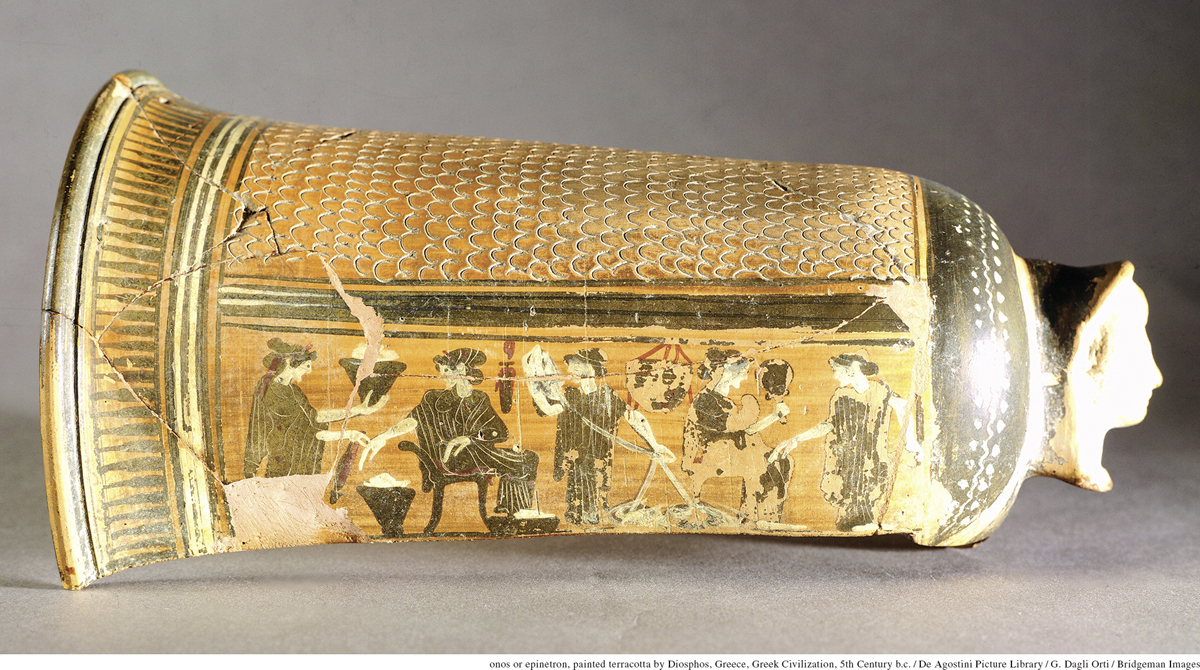

The expansion of slavery added new responsibilities for women. While their husbands farmed, participated in politics, and met with their male friends, well-off wives managed the household: raising the children, supervising the preservation and preparation of food, keeping the family’s financial accounts, weaving fabric for clothing, directing the work of the slaves, and tending them when they were ill. Poor women worked outside the home, laboring in the fields or selling produce and small goods such as ribbons and trinkets in the market. Women’s labor ensured the family’s economic self-sufficiency and allowed male citizens the time to participate in public life.

Women’s religious functions gave them prestige and freedom of movement. Women left the home to attend funerals, state festivals, and public rituals. They had access, for example, to the initiation rites of the popular cult of Demeter at Eleusis, near Athens. Women had control over cults reserved exclusively for them and also performed important duties in other official cults. In fifth-century B.C.E. Athens, for example, women officiated as priestesses for more than forty different deities, with benefits including salaries paid by the state.

Marriages were arranged, and everyone was expected to marry. A woman’s guardian would often engage her to another man’s son while she was still a child, perhaps as young as five. The engagement was a public event conducted in the presence of witnesses. The guardian on this occasion repeated the statement that expressed the primary aim of the marriage: “I give you this woman for the plowing [procreation] of legitimate children.” The wedding took place when the girl was in her early teens and the groom ten to fifteen years older.

A legal wedding consisted of the bride moving to her husband’s dwelling; the procession to his house served as the ceremony. The bride’s father bestowed on her a dowry (a certain amount of family property a daughter received at marriage); if she was wealthy, this could include land yielding an income as well as personal possessions that formed part of her new household’s assets and could be inherited by her children. The husband was legally obliged to preserve the dowry, use it to support his wife and their children, and return it in case of a divorce.

Except in certain cases in Sparta, monogamy was the rule, as was a nuclear family (husband, wife, and children living together without other relatives in the same house). Citizen men, married or not, were free to have sexual relations with slaves, foreign concubines, female prostitutes, or willing pre-adult citizen males. Citizen women, single or married, had no such freedom. Sex between a wife and anyone other than her husband carried harsh penalties for both parties.

REVIEW QUESTION How did the physical, social, and intellectual conditions of life in the Archaic Age promote the emergence of the Greek city-state?

Greek citizen men placed Greek citizen women under their guardianship both to regulate marriage and procreation and to maintain family property. According to Greek mythology, women were a necessary evil. Zeus supposedly ordered the creation of the first woman, Pandora, as a punishment for men in retaliation against Prometheus, who had stolen fire from Zeus and given it to humans. To see what was in a container that had come as a gift from the gods, Pandora lifted its lid and accidentally released into a previously trouble-free world the evils that had been locked inside. When she finally slammed the lid back down, only hope still remained in the container. Hesiod described women as “big trouble” but thought any man who refused to marry to escape the “troublesome deeds of women” would come to “destructive old age” alone, with no heirs. In other words, a man needed a wife so that he could father children who would later care for him and preserve the family property after his death. This paternalistic attitude allowed Greek men to control human reproduction and consequently the distribution of property.