Introduction for Chapter 2

IN THE ILIAD, THE EIGHTH-CENTURY B.C.E. Greek poet Homer narrates bloody tales of the Trojan War. The story is rich with legends born from Greek and Near Eastern traditions, such as that of the Greek hero Bellerophon. Driven from his home by a false charge of sexual assault, Bellerophon has to serve as an enforcer for a foreign king, fighting his most dangerous enemies. In his most famous combat, Bellerophon is pitted against “the Chimera, an inhuman freak created by the gods, horrible with its lion’s head, goat’s body, and dragon’s tail, breathing fire all the time.” Bellerophon triumphs by mounting the winged horse Pegasus and swooping down on the Chimera with an aerial attack. To reward such heroics, the king gives Bellerophon his daughter in marriage and half his kingdom.

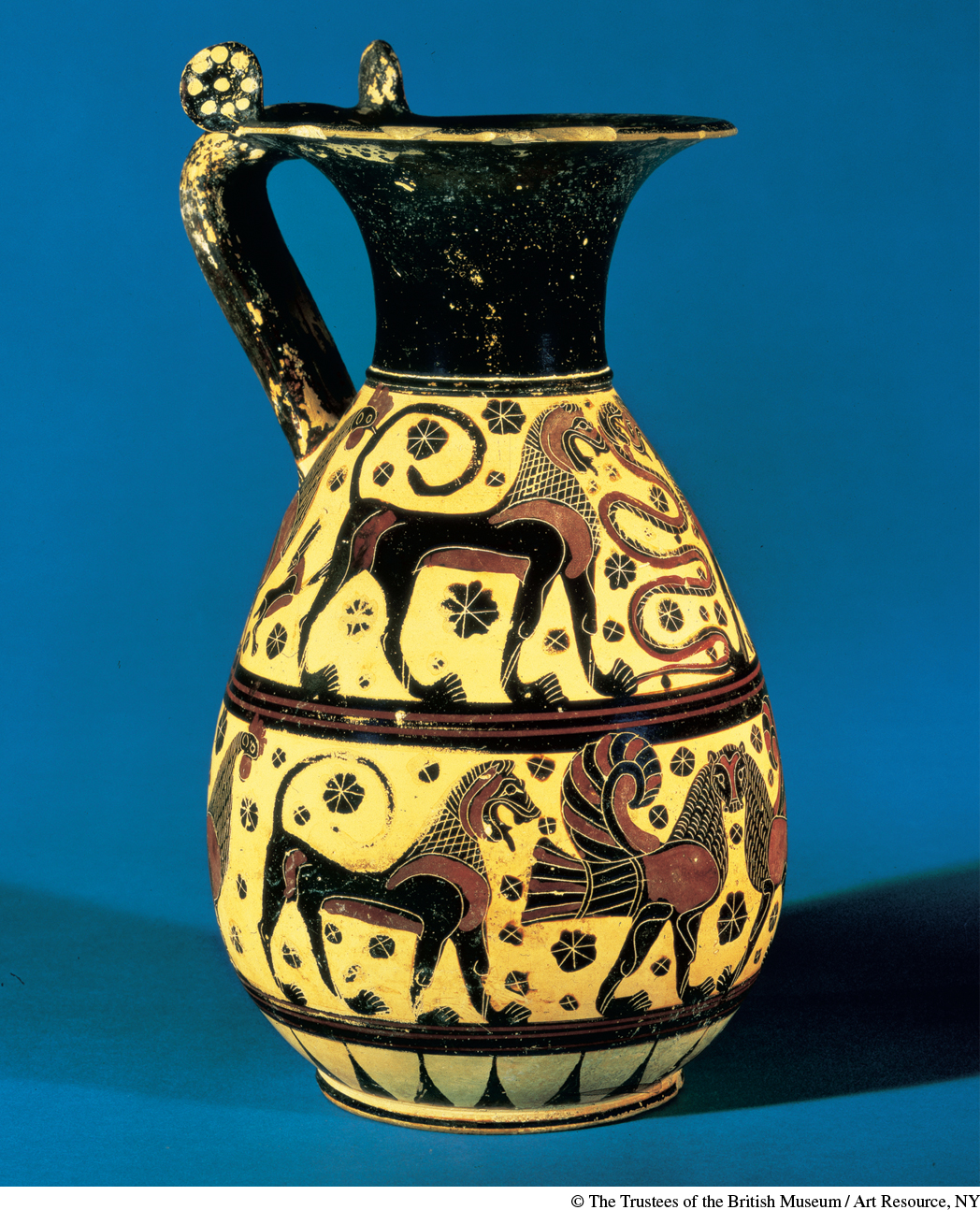

Homer’s story provides evidence for the intercultural contact between the Near East and Greece that helped Greek civilization reemerge after 1000 B.C.E. Both the Chimera and the winged beast painted on the vase from Corinth shown in the chapter-opening illustration were creatures from Near Eastern myth that Greeks adapted. Greece’s geography allowed it many ports, which promoted contacts by sea through trade, travel, and war with the Near East. From 1000 to 500 B.C.E., these contacts—combined with the Greeks’ value of competitive individual excellence, their sense of a communal identity, and their belief that people in general were responsible for maintaining justice and the goodwill of the gods toward the community—aided Greeks in reinventing their civilization.

Western peoples’ desire for trade and cross-cultural contact increased as conditions improved after 1000 B.C.E. The Near East, which retained monarchy as its traditional form of government, recovered more quickly than Greece. Near Eastern kings extracted surpluses from subject populations to fund their palaces and armies. They also pursued new conquests to win glory, exploit the labor of conquered peoples, seize raw materials, and conduct long-distance trade.

During Greece’s initial recovery from poverty and depopulation from 1000 to 750 B.C.E., new political and social traditions arose that rejected the rule of kings. In this period, Greeks maintained trade and cross-cultural contact with the Near East. Their mythology, as in Homer, and their art, as on the Corinthian vase, reveal that Greeks imported ideas and technology from that part of the world. By the eighth century B.C.E., Greeks had begun to create their own kind of city-state, the polis. The polis was a radical innovation because it made citizenship—not subjection to kings—the basis for society and politics, and included the poor as citizens. Women in the polis had legal, though not political, rights; slaves still had neither. With the exception of occasional tyrannies, Greek city-states governed themselves by having male citizens share political power. In some places, small groups of upper-class men dominated, but in other city-states the polis shared power among all free men, even the poor, eventually creating the world’s first democracies. The Greeks’ invention of democratic politics, limited though it might have been by modern standards, stands as a landmark in the history of Western civilization.

CHAPTER FOCUS How did the forms of political and social organization that Greece developed after 1000 B.C.E. differ from those of the Near East?

New ways of belief and thought also developed in the Near East and Greece that deeply influenced Western civilization. In religion, the Persians developed beliefs that saw human life as a struggle between good and evil, and the Israelites evolved their monotheism. In philosophy, the Greeks began to use reason and logic to replace mythological explanations of nature.