Oligarchy in the City-State of Sparta, 700–500 B.C.E.

Oligarchy in the City-State of Sparta, 700–500 B.C.E.

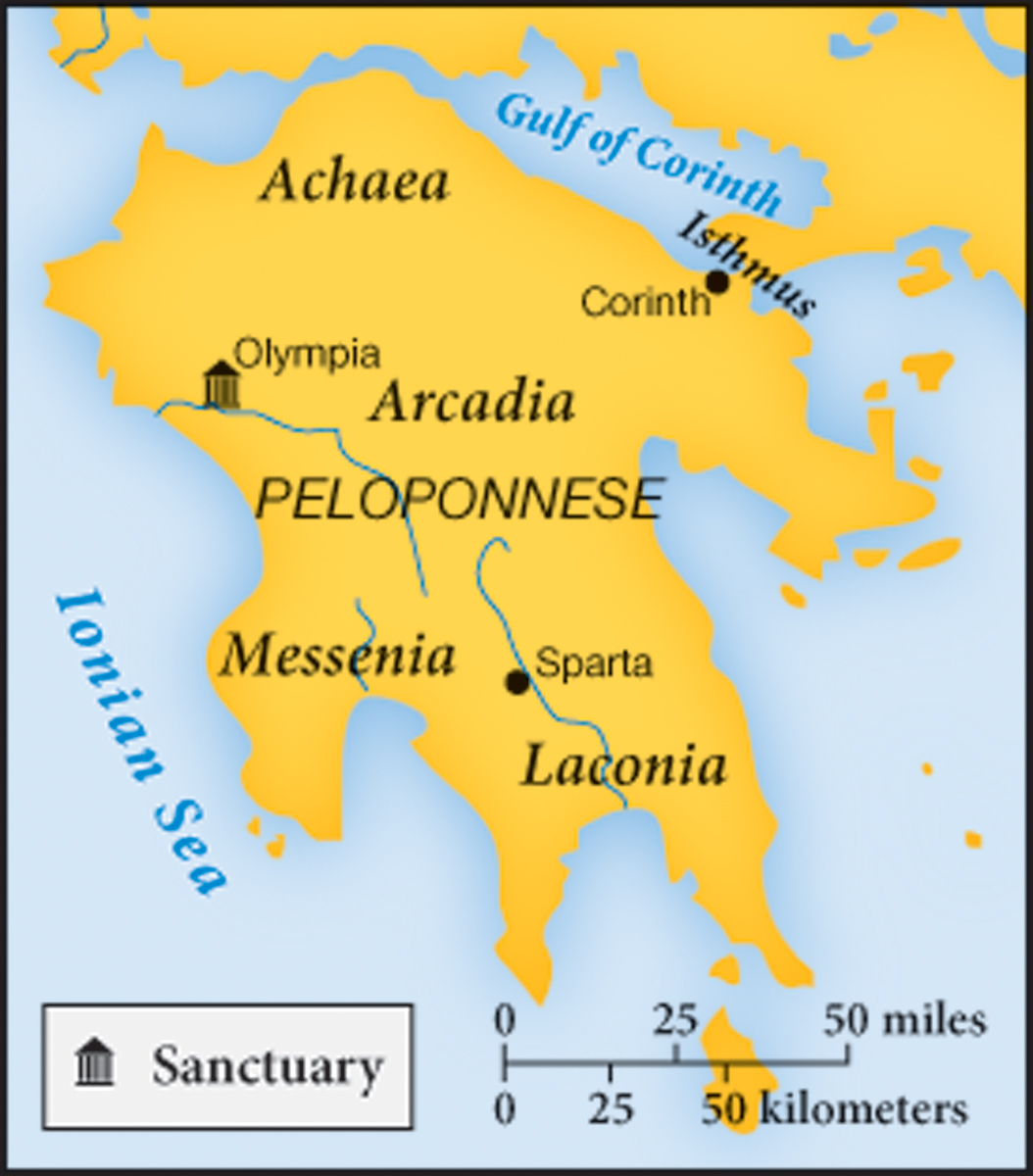

Sparta organized its society for military readiness. This oligarchic city-state developed the mightiest infantry force in Greece during the Archaic Age. Its citizens were famous for their militaristic self-discipline. Sparta’s urban center nestled in an easily defended valley on the Peloponnesian peninsula twenty-five miles from the Mediterranean coast. This separation from the sea kept the Spartans focused on being a land power.

The Spartan oligarchy included three components of rule. First came the two hereditary, prestigious military leaders called kings, who served as the state’s religious heads and the generals of its army. Despite their title, they were not monarchs but just one part of the ruling oligarchy. The second part was a council of twenty-eight men over sixty years old (the elders), and the third part consisted of five annually elected officials called ephors (“overseers”), who made policy and enforced the laws.

In principle, legislation had to be approved by an assembly of all Sparta’s free adult males, who were called “The Alike” to stress their common status and purpose. The assembly had only limited power to amend the proposals put before it, however, and the council would withdraw a proposal when the assembly’s reaction proved negative. Spartan society demanded strict obedience to all laws. When the ephors took office, they issued an official proclamation to Sparta’s males: “Shave your mustache and obey the laws.” Unlike other Greeks, the Spartans never wrote down their laws. Instead, they preserved their system with a unique, highly structured way of life. All Spartan citizens were expected to put service to their city-state before personal concerns because their state’s survival was continually threatened by its own economic foundation: the great mass of Greek slaves, called helots, who did almost all the work for Spartan citizens.

A helot was a slave owned by the Spartan city-state. Helots were Greeks captured in neighboring parts of Greece that the Spartans defeated in war. Most helots lived in Messenia, to the west, which Sparta had conquered by around 700 B.C.E. The helots outnumbered Sparta’s free citizens. Harshly treated by their Spartan masters, helots constantly looked for chances to revolt.

Helots had some family life because they were expected to produce children to maintain their population, and they could own some personal possessions and practice their religion. They labored as farmers and household slaves so that Spartan citizens would not have to do nonmilitary work. Spartan men wore their hair very long to show they were warriors rather than laborers.

Helots lived under the constant threat of officially approved violence by Spartan citizens. Every year the ephors formally declared war between Sparta and the helots, allowing any Spartan to kill a helot without legal penalty or fear of offending the gods. By beating the helots frequently, forcing them to get drunk in public as an object lesson to young Spartans, and humiliating them by making them wear dog-skin caps, the Spartans emphasized their slaves’ “otherness.” In this way Spartans created a justification for their harsh abuse of fellow Greeks. A later Athenian observed, “Sparta is the home of the freest of the Greeks, and of the most enslaved.”

With helots to work the fields, male citizens could devote themselves full-time to preparation for war, training to protect their state from both hostile neighbors and its own slaves. Boys lived at home until their seventh year, when they were sent to live in barracks with other males until they were thirty. They spent most of their time exercising, hunting, practicing with weapons, and learning Spartan values by listening to tales of bravery and heroism at shared meals, where adult males in groups of about fifteen usually ate instead of at home. Discipline was strict, and the boys were purposely underfed so that they would learn stealth tactics by stealing food. If they were caught, punishment and disgrace followed immediately. One famous Spartan tale reported that a boy hid a stolen fox under his clothing and let the panicked animal rip out his insides rather than allow himself to be detected in the theft. A Spartan male who could not survive the tough training was publicly disgraced and denied the status of being an Alike.

Spending so much time in shared quarters schooled Sparta’s young men in their society’s values. The community took the place of a Spartan boy’s family when he was growing up and remained his main social environment even after he reached adulthood. There he learned to call all older men “Father,” to emphasize that his primary loyalty was to the group instead of his biological family. This way of life trained him for the one honorable occupation for Spartan men: obedient soldier. A seventh-century B.C.E. poet expressed the Spartan male ideal: “Know that it is good for the city-state and the whole people when a man takes his place in the front row of warriors and stands his ground without flinching.”

An adolescent boy’s life often involved what in today’s terminology would be called a homosexual relationship, although the ancient concepts of heterosexuality and homosexuality do not match modern notions. An older male would choose a teenager as a special favorite, in many cases engaging him in sexual relations. Their bond was meant to make each ready to die for the other in battle. Numerous Greek city-states included this form of sexuality among their customs, although some thought it disgraceful and made it illegal. The Athenian author Xenophon (c. 430–355 B.C.E.) wrote a work on the Spartan way of life denying that sex with boys existed there because he thought it a stain on the Spartans’ reputation for virtue. However, other sources testify that such relationships did exist in Sparta and elsewhere.

In such relationships the elder partner (the “lover”) was supposed to help educate the young man (the “beloved”) in politics and community values, and not just exploit him for physical pleasure. Once they became adults, beloveds were expected to find a wife to start a family; they could also at that point become the “lover” of an adolescent “beloved.” Sex between adult males was considered disgraceful, as was sex between females of all ages (at least according to men).

Spartan women were known throughout the Greek world for their personal freedom. Since their husbands were so rarely at home, women totally controlled the households, which included servants, daughters, and sons who had not yet left for their communal training. Consequently, Spartan women exercised even more power at home than did women elsewhere in Greece. They could own property, including land. Wives were expected to stay physically fit so that they could bear healthy children to keep up the population. They were also expected to drum Spartan values into their children. One mother became legendary for handing her son his shield on the eve of battle and sternly telling him, “Come back with it or [lying dead] on it.”

Demographics determined Sparta’s long-term fate. The population of Sparta was never large. Adult males—who made up the army—numbered between eight and ten thousand in the Archaic period. Over time, the problem of producing enough children to keep the Spartan army from shrinking became desperate, probably because losses in war far outnumbered births and regulations on the timing of intercourse in marriage had the opposite of the intended effect, reducing instead of increasing fertility. Men became legally required to marry, with bachelors punished by fines and public ridicule. A woman could legitimately have children by a man other than her husband, if all three agreed.

Because the Spartans’ survival depended on the exploitation of enslaved Greeks, they believed changes in their way of life must be avoided because any change might make them vulnerable to internal revolts. Some Greeks criticized the Spartan way of life as repressive and monotonous, but the Spartans’ discipline and respect for their laws also gained them widespread admiration.