The Persian Empire, 557–500 B.C.E.

The Persian Empire, 557–500 B.C.E.

Cyrus (r. c. 557–530 B.C.E.) founded the Persian Empire in what is today Iran through his skills as a general and a diplomat who saw respect for others’ religious practices as good imperial policy. He conquered Babylon in 539 B.C.E. Cyrus won support by proclaiming himself the restorer of traditional religion.

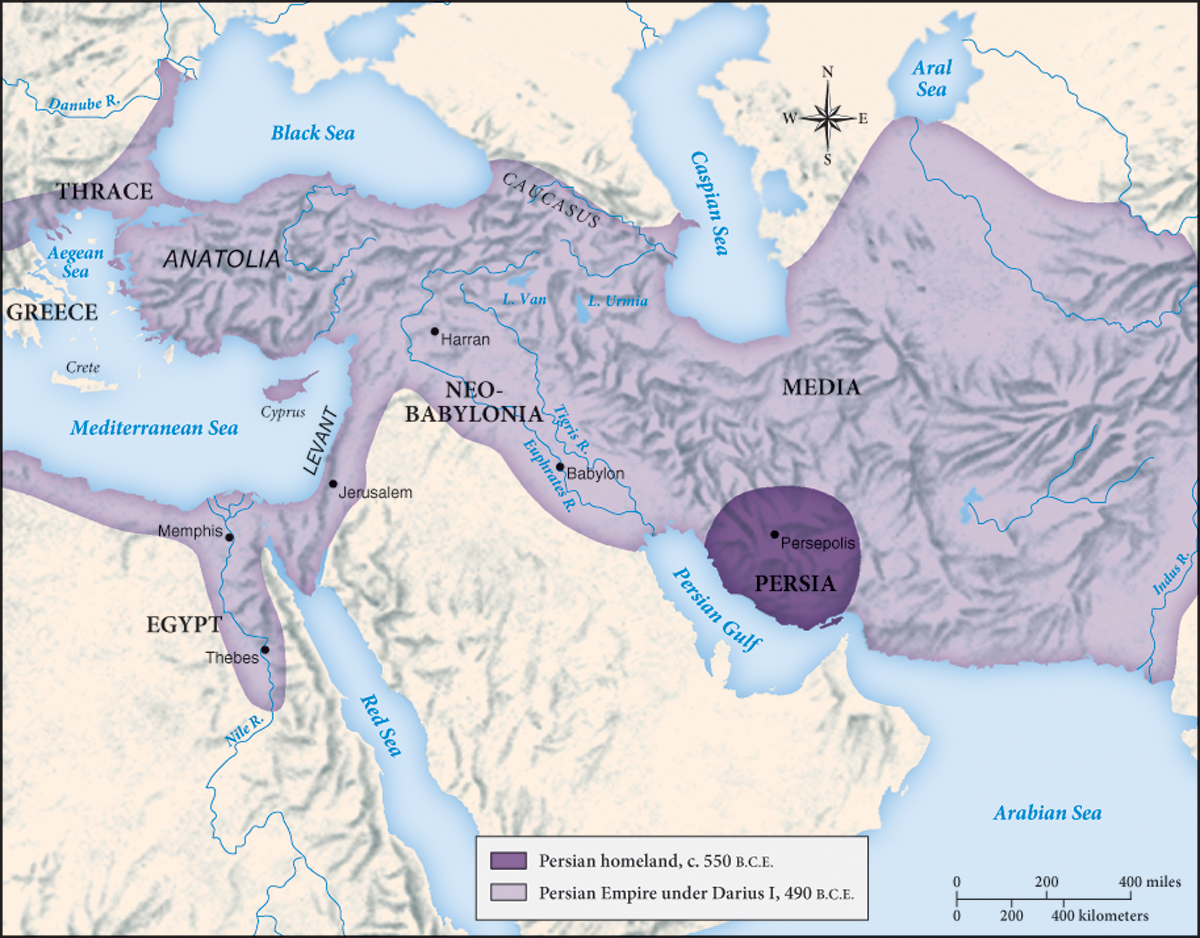

Cyrus’s successors expanded Persian rule on the same principles of military strength and cultural tolerance. At its height, the Persian Empire extended from Anatolia (today Turkey), the eastern Mediterranean coast, and Egypt on the west to present-day Pakistan on the east (Map 2.1). Believing they had a divine right to rule everyone in the world, Persian kings continually tried to expand their empire.

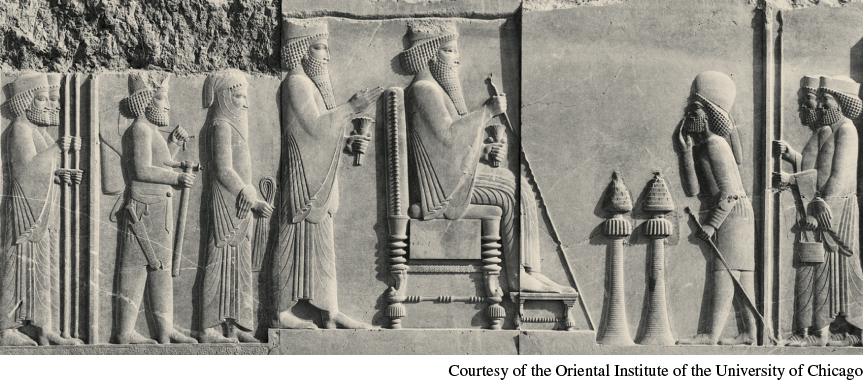

Everything about the king emphasized his magnificence. His robes of purple outshone everyone else’s; only he could step on the red carpets spread for him; his servants held their hands before their mouths so that he would not have to breathe the same air as they. As in other Near Eastern royal art, the Persian king was shown as larger than any other person in the sculpture adorning his immense palace at Persepolis. To display his concern for his loyal subjects as well as the gigantic scale of his resources, the king provided meals for fifteen thousand nobles and other guests every day—although he ate hidden from their view. The king punished criminals by mutilating their bodies and executing their families.

So long as his subjects—numbering in the millions and of many different ethnicities—remained peaceful, the king let them live and worship as they pleased. The empire’s satraps (regional governors) ruled enormous territories with little interference from the king. In this decentralized system, the governors’ duties included keeping order, enrolling troops when needed, and sending revenues to the royal treasury.

Darius I (r. 522–486 B.C.E.) extended Persian power eastward to the western edge of India and westward to Thrace, northeast of Greece, creating the Near East’s greatest empire. Darius assigned each region taxes payable in precious metals, grain, horses, and slaves. Royal roads and a courier system provided communication among the far-flung provincial centers. The Greek historian Herodotus reported that neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor darkness slowed the couriers from completing their routes as swiftly as possible.

Persian kings ruled as the agents of Ahura Mazda, the supreme god of Persia. Persian religion, Zoroastrianism, made Ahura Mazda the center of its devotion and took its doctrines from the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra. Zarathustra taught that Ahura Mazda demanded purity from his worshippers and helped those who lived truthfully and justly. The most important doctrine of Zoroastrianism was moral dualism, which saw the world as a battlefield between the divine forces of good and evil. Ahura Mazda, the embodiment of good and light, struggled against the evil darkness represented by the Satan-like figure Ahriman. Human beings had to choose between the way of the truth and the way of the lie, between purity and impurity. In Persian religion only those judged righteous after death made it across “the bridge of separation” to heaven and avoided falling from its narrow span into hell. Persian religion’s emphasis on ethical behavior and on a supreme god had a lasting influence on others, especially the Israelites. (See “Document 2.1: Excerpt from a Gatha.”)