The Urban Landscape in Athens

Printed Page 85

Important EventsThe Urban Landscape in Athens

Golden Age Athens prospered from Delian League dues, war spoils, and profits and taxes from seaborne trade. Its artisans produced goods traded far and wide; the Etruscans in central Italy, for example, imported countless painted vases. All these activities boosted Athens to its greatest prosperity.

Athenians spent their public resources on pay for citizens participating in its democracy and on public buildings, art, and religious festivals. In private life, rich urban dwellers splurged on luxury goods influenced by Persian designs, but most houses remained modest and plain. Archaeology at the city of Olynthus in northeastern Greece has revealed typical homes grouping bedrooms, storerooms, and dining rooms around open-air courtyards. Poor city residents rented small apartments. Toilets consisted of pots indoors and a pit outside the front door. The city paid collectors to dump the waste in the countryside.

Generals won votes by spending their spoils on public running tracks, shade trees, and buildings. The super-rich commander Cimon (c. 510–c. 450 B.C.E.), for example, paid for the Painted Stoa to be built on the edge of Athens’s agora, the central market square. There, shoppers could admire the building’s paintings of Cimon’s family’s military achievements. This sort of contribution was voluntary, but the laws required wealthy citizens to pay for festivals and warship equipment. This financial obligation on the rich was essential because Athens, as usual in ancient Greece, had no regular property or income taxes.

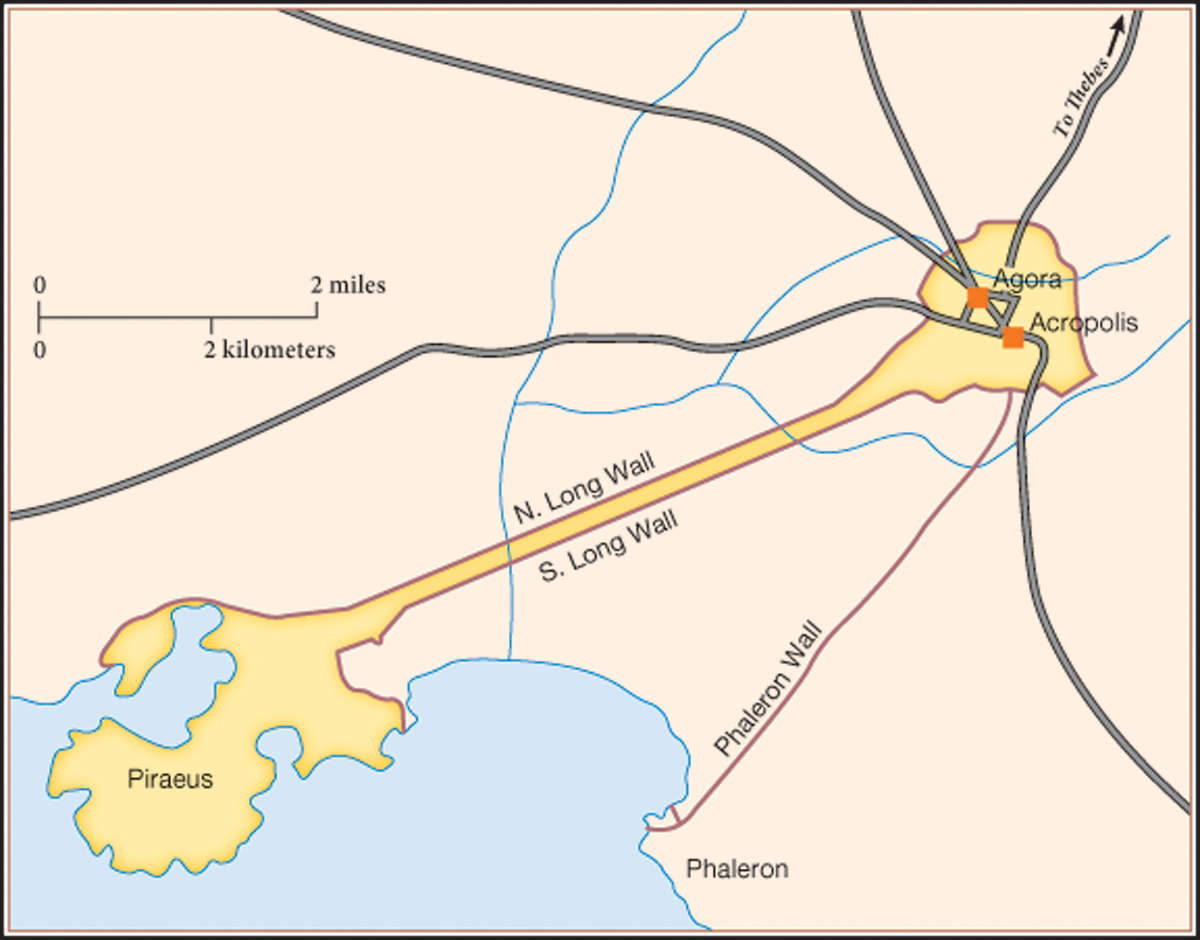

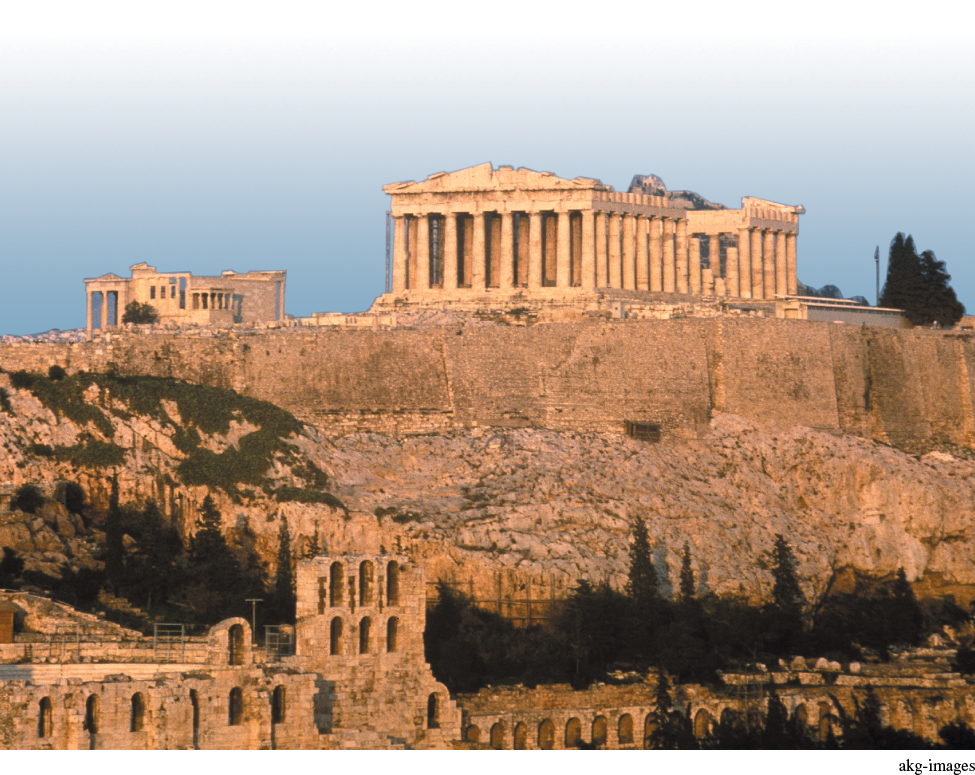

On Athens’s acropolis (the rocky hill at the city’s center, Map 3.2), Pericles had the two most famous buildings of Golden Age Athens erected during the 440s and 430s B.C.E.: a mammoth gateway and an enormous marble temple of Athena called the Parthenon (“virgin goddess’s house”). These two buildings cost more than the equivalent of a billion dollars, a phenomenal sum for a Greek city-state. Pericles’ political rivals slammed him for spending too much public money on the project and diverting Delian League funds to beautify Athens; recent research suggests this accusation was false and that the buildings were financed by Athens’s own revenues.

The Parthenon is the foremost symbol of Athens’s Golden Age. It honored Athena, the city’s chief deity. Inside the temple, a gold-and-ivory statue nearly forty feet high depicted the goddess in armor, holding a six-foot-tall statue of Nike, the goddess of victory.

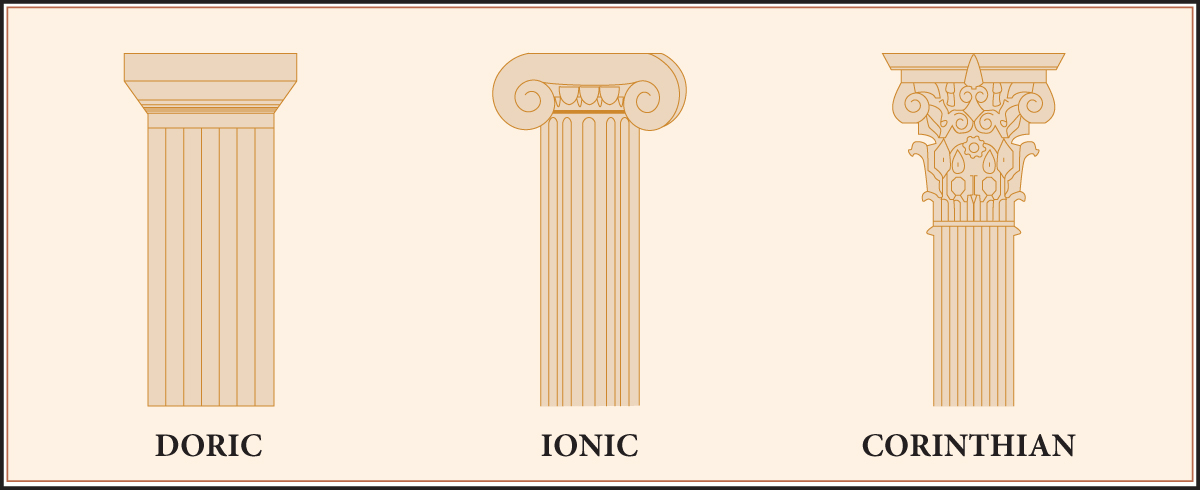

Like all other Greek temples, the Parthenon was a divinity’s residence, not a hall for worshippers. Its design was standard: a rectangular box on a raised platform lined with columns, a plan probably taken from Egypt. The Parthenon’s soaring columns fenced in a porch surrounding the interior chamber. They were carved in the simple style called Doric, in contrast to the more elaborate Ionic and Corinthian styles (Figure 3.2).

The Parthenon’s massive size and innovative style proclaimed the self-confidence of Golden Age Athens and its competitive drive to build a monument more spectacular than any other in Greece. Constructed from twenty thousand tons of local marble, the temple stretched 230 feet long and 100 feet wide. Its complex architecture demonstrated the Athenian ambition to use human skill to improve nature: because perfectly rectilinear architecture appears curved to the human eye, subtle curves and inclines were built into the Parthenon to produce an illusion of completely straight lines and emphasize its massiveness.

The Parthenon’s many sculptures communicated confident messages: the gods ensure triumph over the forces of chaos, and Athenians enjoy the gods’ goodwill more than anyone else. The sculptures in each pediment (the triangular space atop the columns at either end of the temple) portrayed Athena as the city-state’s benefactor. The metopes (panels sculpted in relief above the outer columns around all four sides) portrayed victories over hostile centaurs (creatures with the body of a horse but torso and head of a man) and other enemies of civilization. Most strikingly of all, a frieze (a continuous band of figures carved in relief) ran around the top of the walls inside the porch and was painted in bright colors to make it more visible. The Parthenon’s frieze was special because usually only Ionic-style buildings had one. The frieze showed Athenian men, women, and children parading before the gods, the procession shown in motion like the pictures in a graphic novel today.

No other Greeks had ever adorned a temple with representations of themselves. The Parthenon staked a claim of unique closeness between the city-state and the gods, reflecting the Athenians’ confidence after helping turn back the Persians, achieving leadership of a powerful naval alliance, and accumulating great wealth. Their success, the Athenians believed, proved that the gods were on their side, and their fabulous buildings displayed their gratitude.

Like the unique Parthenon frieze, the innovations that Golden Age artists made in representing the human body shattered tradition. By the time of the Persian Wars, Greek sculptors had begun replacing the stiffly balanced style of Archaic Age statues with statues in motion in new poses. This style of movement in stone expressed an energetic balancing of competing forces, echoing radical democracy’s principles.

Sculptors began carving anatomically realistic but perfect-looking bodies, suggesting that humans could be confident about achieving beauty and perfection. Female statues now displayed the shape of the curves underneath clothing, while male ones showed athletic muscles. The faces showed a more relaxed and self-confident look in place of the rigid smiles of Archaic Age statues.

REVIEW QUESTION What factors produced political change in fifth-century B.C.E. Athens?

Freestanding Golden Age statues, whether paid for with private or government funds, were erected to be seen by the public. Privately commissioned statues of gods were placed in sanctuaries as symbols of devotion. Wealthy families paid for statues of their deceased relatives, especially if they had died young in war, to be placed above their graves as memorials of their excellence and signs of the family’s social status.