From the Ionian Revolt to the Battle of Marathon, 499–490 B.C.E.

From the Ionian Revolt to the Battle of Marathon, 499–490 B.C.E.

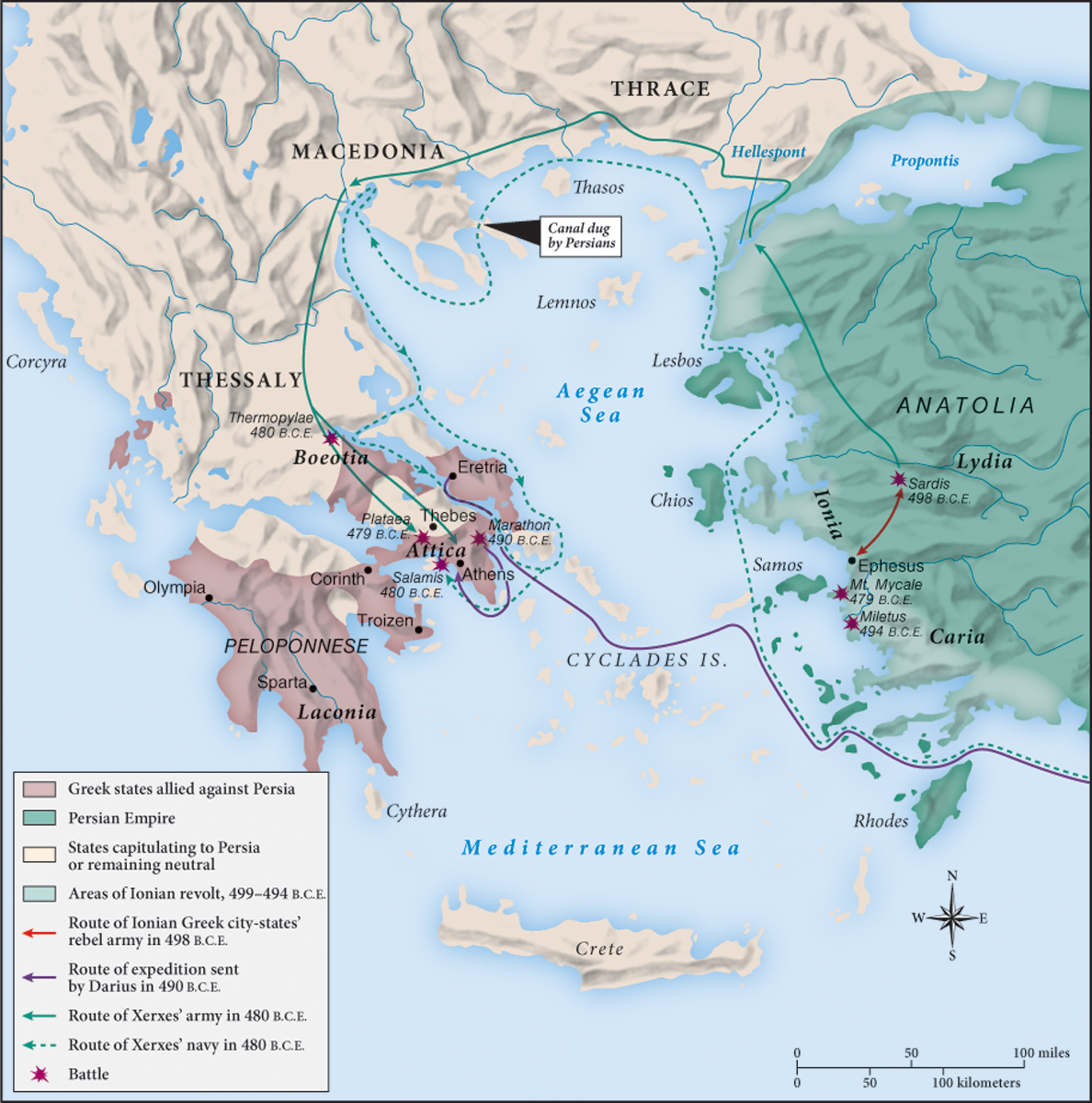

In 499 B.C.E., the Greek city-states in Ionia rebelled against their Persian-installed tyrants. The Athenians sent troops because they saw the Ionians as close kin. By 494 B.C.E., a Persian counterattack had crushed the revolt (Map 3.1). Darius exploded in anger when he learned that the Athenians had helped the Ionian rebels. He even ordered a slave to repeat three times at every meal, “Lord, remember the Athenians.”

In 490 B.C.E., Darius sent a force to punish Athens and install a puppet tyrant. The Athenians confronted the invaders at the town of Marathon, on their coast. The Athenian soldiers were stunned by the Persians’ strange garb—colorful pants instead of the short tunics and bare legs that Greeks regarded as proper dress (see the chapter-opening photo)—but the Greek commanders had their infantry charge the enemy at a dead run. The soldiers in their heavy armor clanked across the plain through a hail of Persian arrows. In the hand-to-hand combat, the Greek hoplites used their long spears to overwhelm the Persian infantry.

The Athenian infantry then hurried the twenty-six miles to Athens to guard the city against the Persian navy. (Today’s marathon races commemorate the legend of a runner speeding ahead to announce the victory, and then dropping dead.) Their unexpected success strengthened the Athenians’ sense of community. When a rich strike was made in Athens’s publicly owned silver mines in 483 B.C.E., a far-sighted leader named Themistocles (c. 524–c. 460 B.C.E.) convinced the assembly to spend the money on doubling the size of the navy instead of on distributing it to the citizens.