The Rule of Alexander the Great, 336–323 B.C.E.

The Rule of Alexander the Great, 336–323 B.C.E.

Philip was murdered in 336 B.C.E. Some scholars think his son Alexander and his son’s mother, Olympias, arranged the killing to seize power for the twenty-year-old Alexander, but the murderer, one of Philip’s bodyguards, was probably motivated by personal anger at the king. Alexander secured his rule by eliminating rivals and defeating Macedonia’s enemies to the west and north with swift attacks. He forced the southern Greeks, who had defected from the alliance at the news of Philip’s death, to rejoin. To demonstrate the cost of disloyalty, in 335 B.C.E. Alexander destroyed Thebes for having rebelled.

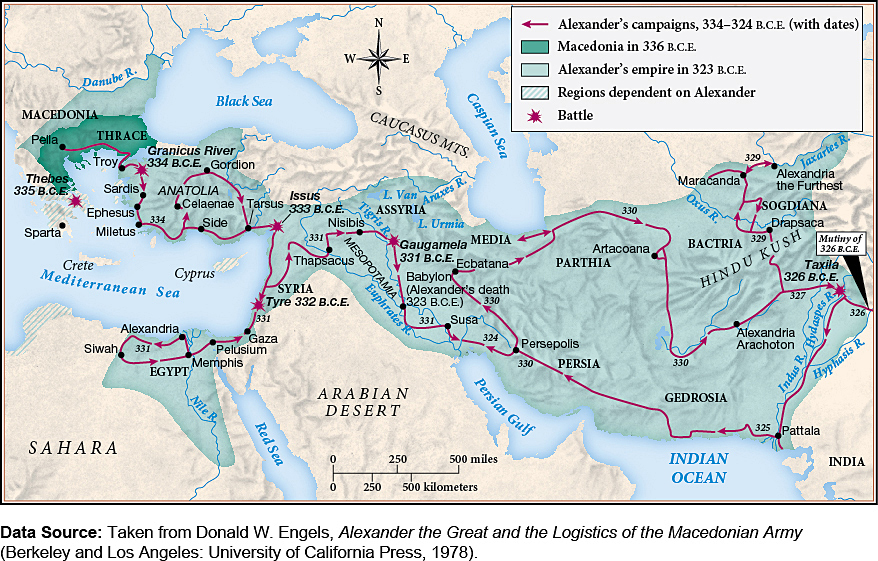

In 334 B.C.E., Alexander launched the most astonishing military campaign in ancient history, leading a Macedonian and Greek army against the Persian Empire to fulfill Philip’s dream of avenging Greece. Alexander’s conquest of all the lands from Turkey to Egypt to Uzbekistan while still in his twenties led later peoples to call him Alexander the Great. Alexander inspired his troops by leading charges against the enemy, riding his warhorse Bucephalas (“oxhead”). Everyone saw him speeding ahead in his plumed helmet, polished armor, and vividly colored cloak. He was so intent on conquest that he rejected advice to delay the war until he had fathered an heir. He gave away nearly all of his land to strengthen ties with his army officers. Alexander aimed at becoming more famous even than Achilles; he always kept a copy of Homer’s Iliad under his pillow—along with a dagger.

Building on Near Eastern traditions of siege technology and Philip’s innovations, Alexander developed even better military technology. When Tyre, a heavily fortified city on an island off the eastern Mediterranean coast, refused to surrender to him in 332 B.C.E., he built a massive stone pier as a platform for artillery towers, armored battering rams, and catapults flinging boulders to breach Tyre’s walls. Knowing that Alexander could overcome their fortifications made enemies much readier to negotiate a deal.

In his conquest of Egypt and the Persian heartland, Alexander revealed his strategy for ruling a vast empire: keep an area’s traditional administrative system in place while founding cities of Greeks and Macedonians in the conquered territory. In Egypt, he established his first new city, naming it Alexandria after himself. In Persia, he proclaimed himself the king of Asia and relied on Persian administrators.

Alexander led his army past the Persian heartland farther east into territory hardly known to the Greeks (Map 4.1). He aimed to outdo the heroes of legend by marching to the end of the world. Shrinking his army to reduce the need for supplies, he marched northeast into what is today Afghanistan and Uzbekistan. Unable to subdue the local guerrilla forces, Alexander settled for an alliance sealed by his marriage to the Bactrian princess Roxane.

Alexander then headed east into India. Seventy days of marching through monsoon rains extinguished his soldiers’ fire for conquest. In the spring of 326 B.C.E., they mutinied, forcing Alexander to turn back. The return journey through southeastern Iran’s deserts cost many casualties from hunger and thirst; the survivors finally reached safety in the Persian heartland in 324 B.C.E. Alexander immediately began planning an invasion of the Arabian peninsula and, after that, of North Africa. He also announced that he wished to receive the honors due a god. Most Greek city-states obeyed by sending religious delegations to him. Personal motives best explain Alexander’s announcement: he had come to believe he was truly the son of Zeus and that his superhuman accomplishments demonstrated that he must himself be a god. (See “Taking Measure: The March of Alexander the Great’s Army.”)

Alexander died from a fever in 323 B.C.E. Unfortunately for the stability of his immense conquests, he had no heir ready to take over his rule. Roxane gave birth to their son only after Alexander’s death. The story goes that, when at Alexander’s deathbed his commanders asked him to whom he left his kingdom, he replied, “To the most powerful.”

Scholars disagree on almost everything about Alexander. Was he a bloodthirsty monster obsessed with war, or a romantic visionary intent on creating a multiethnic world open to all cultures? The ancient sources suggest that Alexander had interlinked goals reflecting his restless and ruthless nature: to conquer and administer the known world with a new ruling class mixing competent people from all ethnic groups, to outdo the exploits and glory of legendary heroes, and to earn the status no living human had ever achieved—that of a god on earth.

REVIEW QUESTION What were the accomplishments of Alexander the Great, and what were their effects both for the ancient world and for later Western civilization?

Alexander’s explorations benefited scientific fields from geography to botany because he took along knowledgeable writers to collect and catalog new knowledge. He had vast quantities of scientific observations dispatched to his old tutor Aristotle. Alexander’s new cities promoted trade between Greece and the Near East. Most of all, his career brought the two cultures into closer contact than ever before. This contact represented his career’s most enduring impact.