Athens’s Recovery after the Peloponnesian War

Athens’s Recovery after the Peloponnesian War

The devastation of Athens’s economy in the Peloponnesian War and overcrowding of refugees from the country in the wartime city produced social conflict. Life became difficult for middle-class women whose male relatives had been killed. With no man to provide for them and their children, many war widows had to work outside the home. The only jobs open to them—such as wet-nursing, weaving, or laboring in vineyards—were low-paying.

Resourceful Athenians found ways to profit from women’s skills. The family of one of Socrates’ friends, for example, fell into poverty when several widowed sisters, nieces, and female cousins moved in. The friend complained to Socrates that he was too poor to support his new family of fourteen plus their slaves. Socrates replied that the women knew how to make clothing, so they should sell it. This plan succeeded financially, but the women then complained that Socrates’ friend was the household’s only member who ate without working. Socrates advised the man to reply that the women should think of him as sheep did a guard dog—he earned his share of the food by keeping the wolves away.

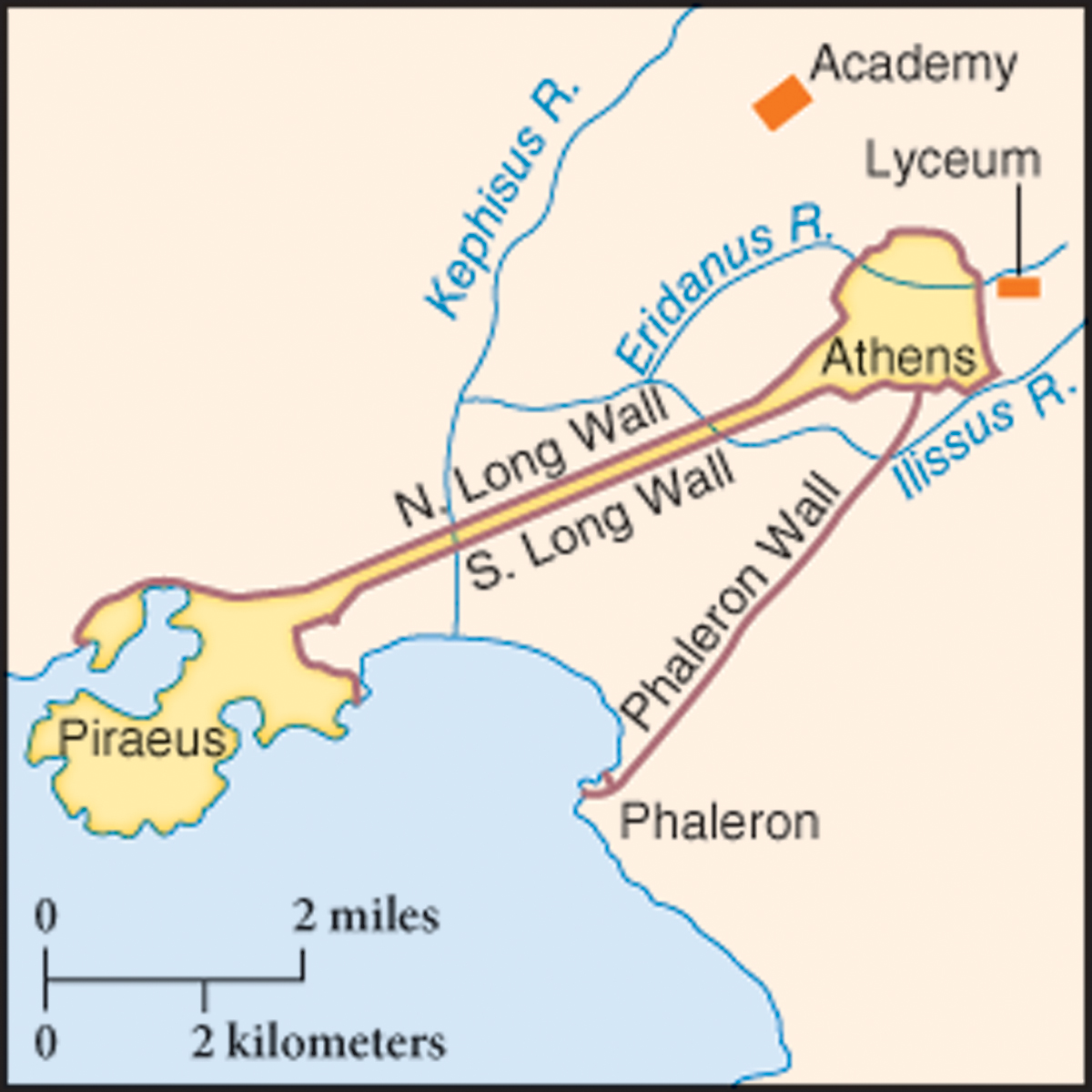

Athens’s postwar economy recovered as international trade was revived once its Long Walls, which protected the transportation corridor from the city to the port, were rebuilt and mining for silver to produce the city’s coinage resumed. Greek businesses producing manufactured goods were small and usually family-run; the largest known was a shield-making company with 120 slave workers. Some changes occurred in occupations formerly defined by gender. For example, men began working alongside women in cloth production when the first commercial weaving shops outside the home sprang up. Some women made careers in the arts, especially painting and music, which men had traditionally dominated.

Daily life remained a struggle for working people. Most workers earned barely enough to feed and clothe their families. They ate two meals a day, with bread baked from barley as their main food; only rich people could afford wheat bread. A family bought bread from small bakery stands, often run by women, or made it at home, with the wife directing the slaves in grinding the grain, shaping the dough, and baking it in a clay oven heated by charcoal. People topped their bread with greens, beans, onions, garlic, olives, fruit, and cheese. The few households rich enough to afford meat boiled or grilled it over a fire. Everyone of all ages drank wine, diluted with water, with every meal.