The Early Roman Republic, 509–287 B.C.E.

The Early Roman Republic, 509–287 B.C.E.

The social elite’s hatred of monarchy motivated the creation of the Roman Republic. In 509 B.C.E., the son of the king raped the virtuous Roman woman Lucretia, who committed suicide to preserve her honor. Her relatives and friends from the social elite responded by overthrowing the king to found the republic. Thereafter, the Romans prided themselves on having a political system based on sharing political power among (male) citizens. (See “Document 5.1: The Rape and Suicide of Lucretia.”)

The Romans struggled for 250 years to shape a stable government for the republic. Roman social hierarchy split the population into two orders: the patricians (a small group of the most aristocratic families) and the plebeians (the rest of the citizens). These two groups’ conflicts over power created the so-called struggle of the orders. The struggle finally ended in 287 B.C.E. when plebeians won the right to make laws in their own assembly.

Patricians constituted a tiny percentage of the population—numbering only about 130 families—but in the beginning of the republic their inherited status entitled them to control public religion and to monopolize political office. Many patricians were much wealthier than most plebeians. Some plebeians, however, were also rich, and they resented the patricians’ dominance, especially their ban on intermarriage with plebeians. Poor plebeians demanded farmland and relief from crushing debts. Patricians inflamed tensions by wearing special red shoes to set themselves apart; later they changed to black shoes adorned with a small metal crescent. To pressure the patricians, the plebeians periodically refused military service. This tactic worked because Rome’s army depended on plebeian manpower.

In response to plebeian unrest, the patricians agreed to the earliest Roman law code. This code, enacted between 451 and 449 B.C.E. and known as the Twelve Tables, guaranteed greater equality and social mobility. The Twelve Tables prevented patrician judges from giving judgments in legal cases only according to their own wishes. The Roman belief in fair laws as the best protection against social strife helped keep the republic united until the late second century B.C.E.

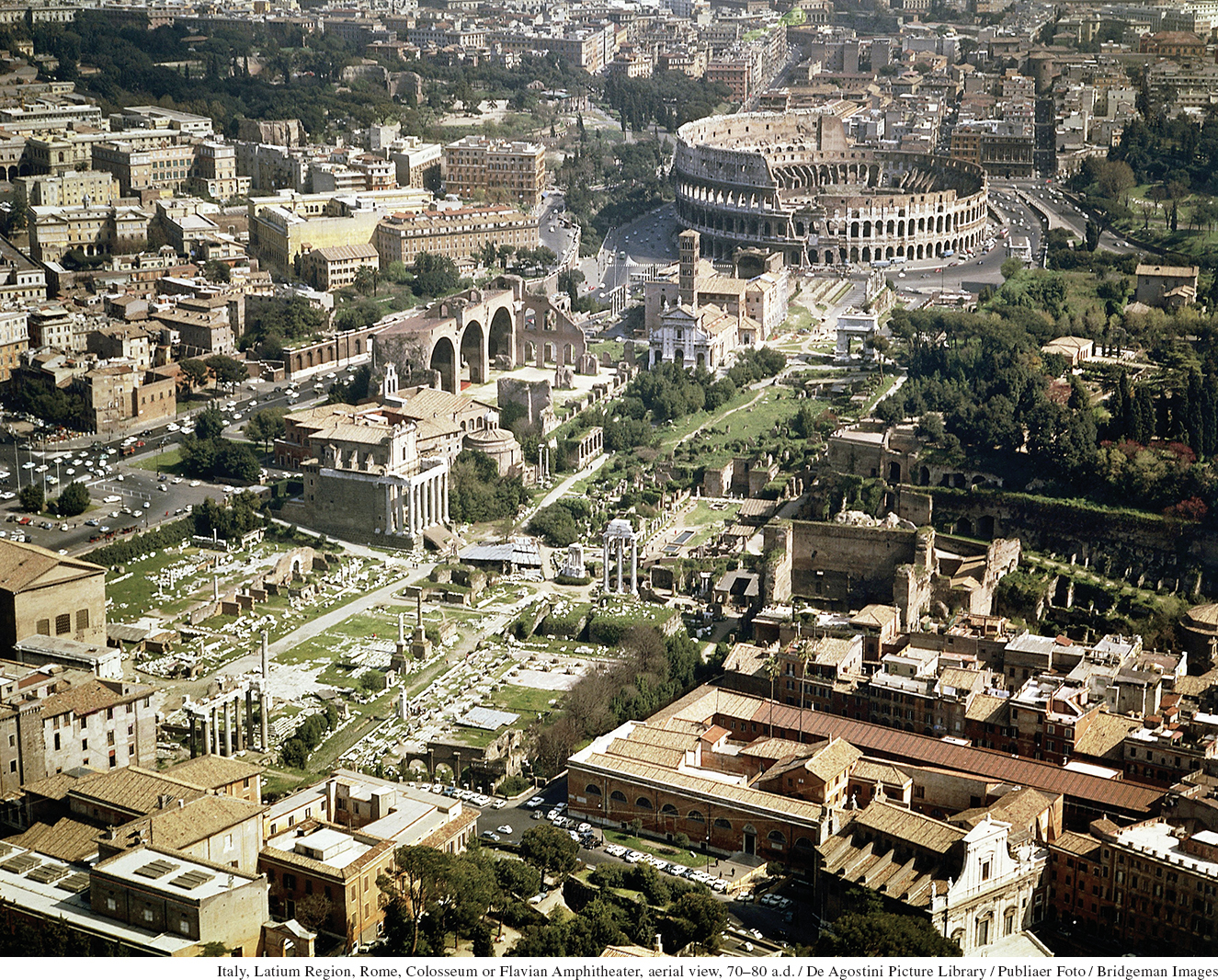

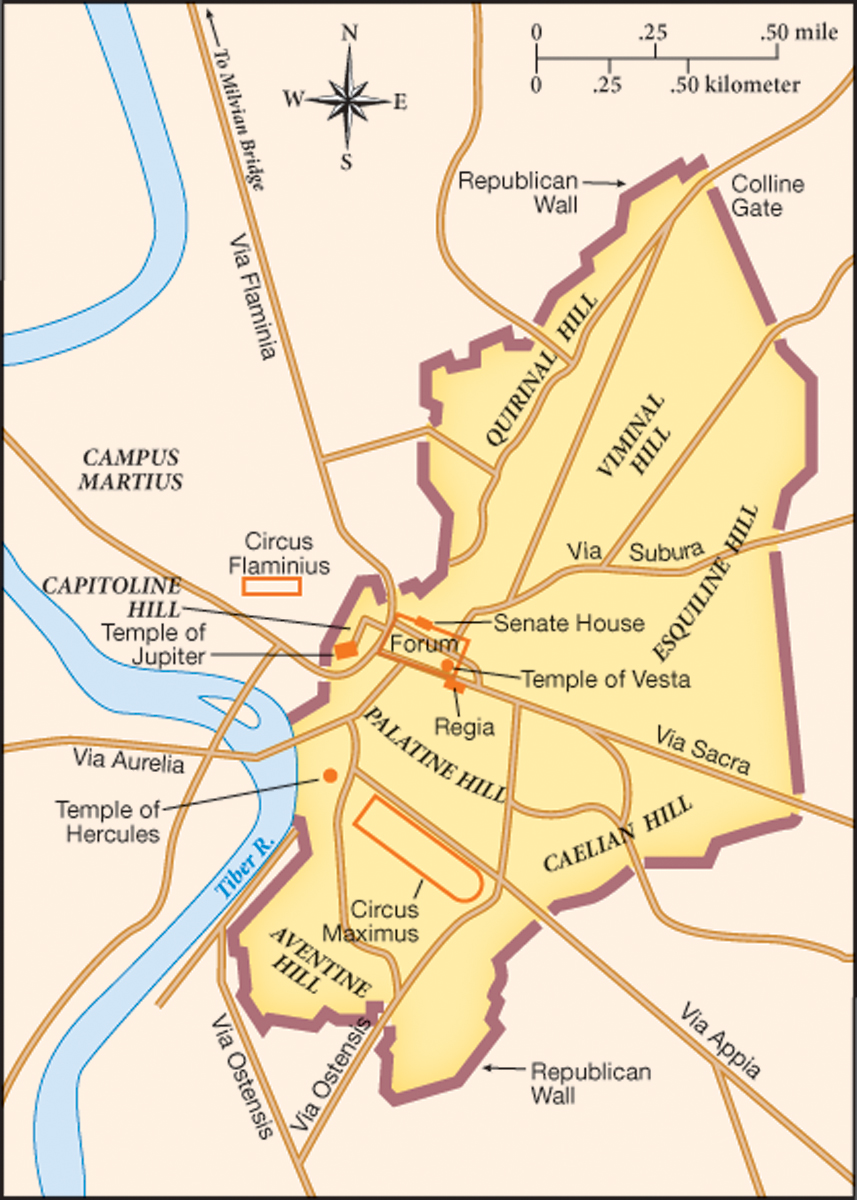

The voting to elect officials took place around the forum in the city center (Map 5.2). All officials worked as part of committees, to ensure power sharing. The highest officials, two elected each year, were called consuls. Their most important duty was to command the army.

To be elected consul, a man had to win elections all the way up a ladder of offices (cursus honorum). Before politics, however, came ten years of military service from about age twenty. The ladder’s first step was getting elected quaestor (a financial administrator). Next was election as an aedile (supervisors of Rome’s streets, sewers, aqueducts, temples, and markets). The third step was election as praetor (a powerful office with judicial and military duties). The most successful praetors competed to be one of the two consuls elected each year. Praetors and consuls held imperium (the power to command and punish) and served as army generals. Families with a consul among their ancestors were honored as nobles. By 367 B.C.E., the plebeians had forced passage of a law requiring that at least one of the two consuls be a plebeian. Ex-consuls competed to become one of the censors, elected every five years to conduct censuses of the citizen body and to appoint new senators. To be eligible for selection to the Senate, a man had to have been at least a quaestor.

The patricians tried to monopolize the highest offices, but after violent struggle from about 500 to 450 B.C.E., the plebeians forced the patricians to create ten annually elected plebeian officials, called tribunes, who could stop actions that would harm plebeians or their property. The tribunate did not count as a regular ladder office. Tribunes based their special power on the plebeians’ sworn oath to protect them, and on their authority to block officials’ actions, prevent laws from being passed, suspend elections, and contradict the Senate’s advice. The tribunes’ extraordinary power to veto government action often made them agents of political conflict.

Men competed in elections to win respect and glory, not money. Only well-off men could serve in government because officials earned no salaries and were expected to spend their own money to pay for public works and for expensive shows featuring gladiators and wild animals. In the early republic, officials’ only reward was respect, but as Romans conquered overseas territory, the desire for money from plunder overcame many men’s adherence to traditional Roman values of faithfulness and honesty. By the second century B.C.E., military officers were also enriching themselves by extorting bribes as administrators of conquered territories.

The Senate directed government policy by giving advice to the consuls. The senators’ social standing gave their opinions great weight. To make their status visible, the senators wore black high-top shoes and robes with a broad purple stripe. If a consul rejected the Senate’s advice, a political crisis ensued.

Three different assemblies made legislation, conducted elections, and rendered judgment in certain trials. The Centuriate Assembly, which elected praetors and consuls, was dominated by patricians and rich plebeians. The Plebeian Assembly, which excluded patricians, elected the tribunes. In 287 B.C.E., its resolutions, called plebiscites, became legally binding on all Romans. The Tribal Assembly mixed patricians with plebeians and became the republic’s most important assembly. Each assembly was divided into groups, with each group comprising a different number of men based on status and wealth; each group had one vote.

Before assembly meetings, orators gave speeches about issues. Everyone, including women and noncitizens, could listen to these pre-vote speeches. The crowd expressed its opinions by either applauding or hissing. This process mixed a small measure of democracy with the republic’s oligarchy.

Early on, the praetors decided most legal cases. A separate jury system arose in the second century B.C.E., and senators repeatedly clashed with other upper-class Romans over whether these juries should consist exclusively of senators. Accusers and accused had to speak for themselves in court, or have friends speak for them. Priests dominated in legal knowledge until the third century B.C.E., when senators with legal expertise, called jurists, began to offer advice about cases.

REVIEW QUESTION How and why did the Roman republic develop its complicated political and judicial systems?

The Roman Republic’s complex political and judicial system evolved in response to conflicts over power. Laws could emerge from different assemblies, and legal cases could be decided by various institutions. Rome had no single highest court, such as the U.S. Supreme Court, to give final verdicts. The republic’s stability therefore depended on maintaining the mos maiorum. Because they defined this tradition, the most socially prominent and richest Romans dominated politics and the courts.