Expansion in Italy, 500–220 B.C.E.

Expansion in Italy, 500–220 B.C.E.

After defeating their Latin neighbors in the 490s B.C.E., the Romans spent the next hundred years warring with the nearby Etruscan town of Veii. Their 396 B.C.E. victory doubled their territory. By the fourth century B.C.E., the Roman infantry legion of five thousand men had surpassed the Greek and Macedonian infantry phalanx as an effective fighting force because in the legion’s more flexible battle line the soldiers were trained to throw javelins from behind their long shields and then rush in to finish off the enemy with swords. A devastating sack of Rome in 387 B.C.E. by marauding Gauls (Celts) from beyond the Alps made Romans forever fearful of foreign invasion. By around 220 B.C.E., Rome controlled all of Italy south of the Po River, at the northern end of the peninsula.

The Romans combined brutality with diplomacy to control conquered peoples. Sometimes they enslaved the defeated or forced them to surrender large parcels of land. Other times they offered generous peace terms to former enemies but required them to join in fighting against other foes, for which they received a share of the spoils, mainly slaves and land.

To increase homeland security, the Romans planted numerous colonies of relocated citizens and constructed roads up and down the peninsula to allow troops to travel faster. By connecting Italy’s diverse peoples, these settlements promoted a unified culture dominated by Rome. Latin became the common language, although some local tongues lived on.

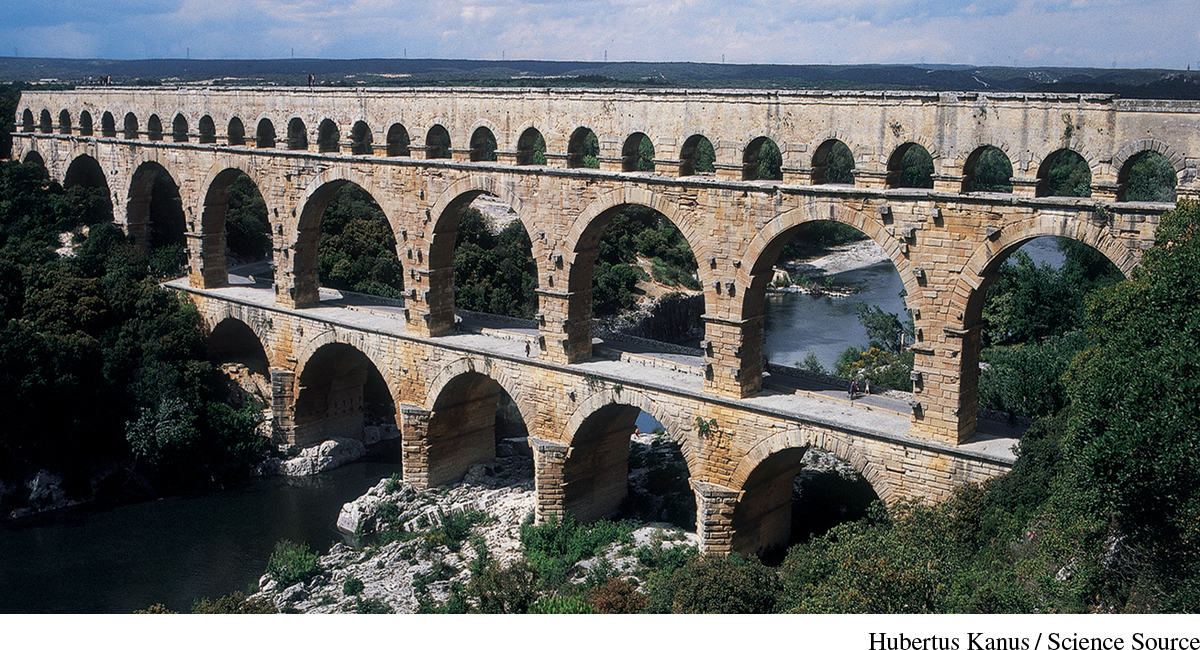

The wealth of its army attracted hordes of people to Rome, where new aqueducts provided fresh, running water and a massive building program employed many. By 300 B.C.E., about 150,000 people lived within Rome’s walls (Map 5.2, page 154). Outside the city, around 750,000 free Roman citizens inhabited various parts of Italy on land that had been taken from local peoples. Much conquered territory was declared public land, open to any Roman for grazing cattle.

Rich plebeians and patricians cooperated to exploit the expanding Roman territories, deriving their wealth from agricultural land and war plunder. Since Rome had no regular income or inheritance taxes, families could pass down their wealth from generation to generation freely.