Stresses on Society from Imperialism

Stresses on Society from Imperialism

The wars of the third and second centuries B.C.E. damaged small farmers, creating grave social and economic difficulties for the republic. The long deployments of troops abroad disrupted Rome’s agricultural system, the economy’s foundation. A farmer absent during a protracted war had to rely on a hired hand or slave to manage his crops and animals, or have his wife perform farm work in addition to her usual family responsibilities.

The story of the consul Regulus, who won a great victory in Africa in 256 B.C.E., revealed the problems that prolonged absence caused. When the man who managed Regulus’s farm died while the consul was away fighting, a worker stole all the farm’s tools and livestock. Regulus begged the Senate to send a replacement fighter so that he could return to save his wife and children from starving. The senators instead sent help to preserve Regulus’s family and property because they wanted to keep him on the battle lines.

Ordinary soldiers received no special aid, and economic troubles hit them hard when, in the second century B.C.E., for unknown reasons, there was no longer enough farmland to support the population. The rich had deprived the poor of land, but recent research suggests that an increase in the number of young people created the crisis. Not all regions of Italy suffered as severely as others, and some impoverished farmers and their families survived by working as agricultural laborers for others. Many homeless people, however, relocated to Rome, where the men begged for work and women made cloth or, in desperation, became prostitutes.

This flood of landless poor created an explosive element in Roman politics by the late second century B.C.E. The government had to feed its poor citizens to avert riots, so Rome needed to import grain. The poor’s demand for low-priced (and eventually free) food distributed at state expense became one of the most divisive issues in the late republic.

While the landless poor struggled, imperialism meant political and financial rewards for Rome’s social elite. The need for commanders to lead military campaigns abroad created opportunities for successful generals to enrich their families. The elite enhanced their reputations by spending their gains to finance public works that benefited the general population. Building new temples, for example, won praise because the Romans believed it pleased their gods to have many shrines.

The troubles of small farmers enriched landowners who could buy bankrupt farms to create large estates. Some landowners also illegally occupied public land carved out of territory seized from defeated enemies. The rich worked their huge farms, called latifundia, with free laborers as well as slaves who had been taken captive in the same wars that displaced so many farmers. The size of the latifundia slave crews made their periodic revolts so dangerous that the army had to fight hard to suppress them.

The elite profited from Rome’s expansion by filling the governing offices in the new provinces. Some governors ruled honestly, but others used their power to extort the locals. Since martial law ruled, no one in the provinces could curb a greedy governor’s appetite for graft and extortion. Often such offenders escaped punishment because their fellow senators excused their crimes.

REVIEW QUESTION What advantages and disadvantages did Rome’s victories over foreign peoples create for both rich and poor Romans?

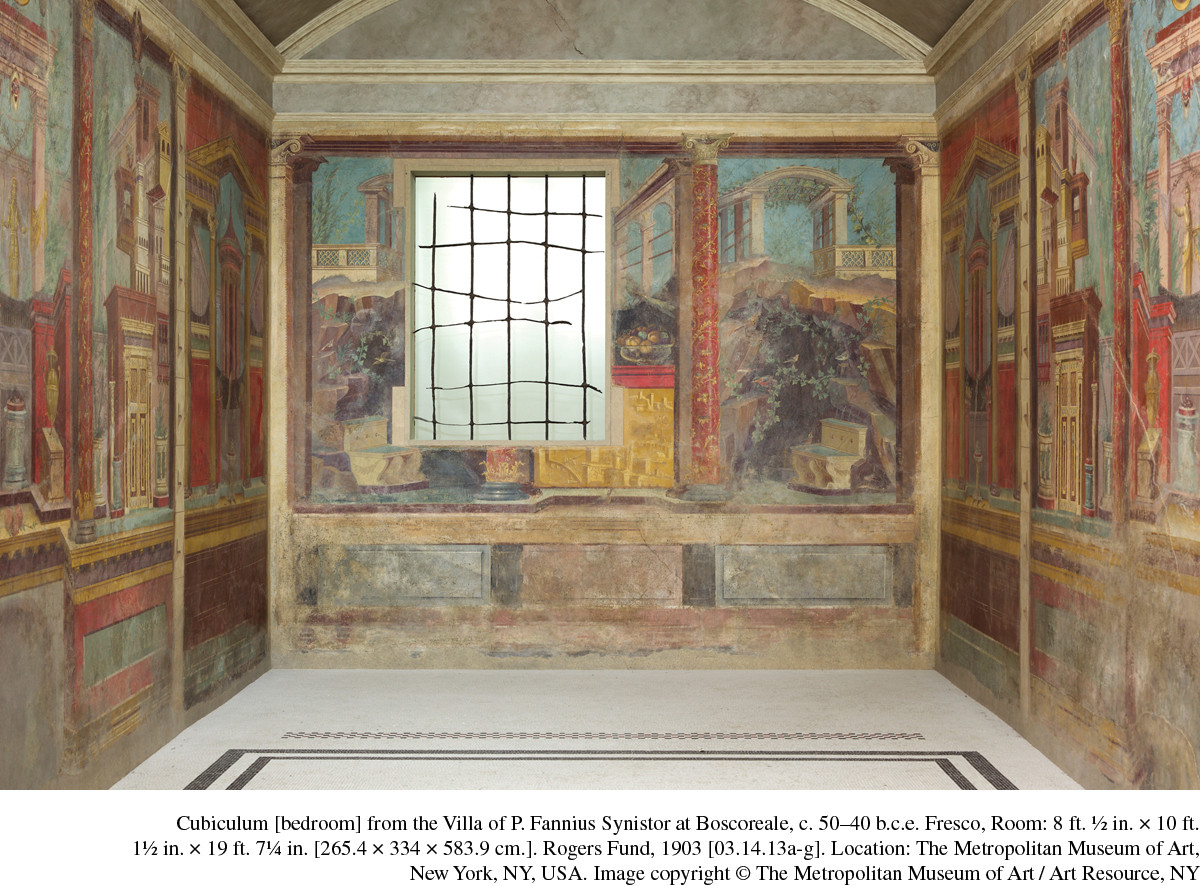

The new opportunities for rich living strained the traditional values of moderation and frugality. Previously, a man could become legendary for his life’s simplicity: Manius Curius (d. 270 B.C.E.), for example, boiled turnips for his meals in a humble hut despite his glorious military victories. Now the elite acquired showy luxuries, such as large country villas for entertaining friends and clients. Money had become more valuable to them than the republic’s ancestral values.