Julius Caesar and the Collapse of the Republic, 83–44 B.C.E.

Julius Caesar and the Collapse of the Republic, 83–44 B.C.E.

Powerful generals after Sulla proclaimed their loyalty to the community while in reality ruthlessly pursuing their own advancement. The competition for power and money between Gnaeus Pompey and Julius Caesar, two Roman aristocrats, generated the civil war that ended the Roman Republic and led to the return of monarchy. (See “Contrasting Views: What Was Julius Caesar Like”?)

Pompey (106–48 B.C.E.) was a brilliant general. In his early twenties he won victories supporting Sulla. In 71 B.C.E., he won the mop-up battles defeating a massive slave rebellion led by a gladiator named Spartacus, stealing the glory from the real victor, Marcus Licinius Crassus. (Spartacus had terrorized southern Italy for two years and defeated consuls with his army of 100,000 escaped slaves.) Pompey shattered tradition by demanding and receiving a consulship for 70 B.C.E., even though he was nowhere near the legal age of forty-two and had not been elected to any lower post on the ladder of offices. Three years later, he received a command to exterminate the pirates who were then infesting the Mediterranean, a task he accomplished in a matter of months. This success made him wildly popular with many groups: the urban poor, who depended on a steady flow of imported grain; merchants, who depended on safe sea lanes; and coastal communities, which were vulnerable to pirates’ raids. In 66 B.C.E., he defeated Mithridates, who was still stirring up trouble in Asia Minor. By annexing Syria as a province in 64 B.C.E., Pompey ended the Seleucid kingdom and extended Rome’s power to the Mediterranean’s eastern coast.

People compared Pompey to Alexander the Great and added Magnus (“the Great”) to his name. He ignored the tradition of consulting the Senate about conquering and administering foreign territories, and behaved like an independent king. He summed up his attitude by replying to some foreigners who criticized his actions as unjust: “Stop quoting the laws to us,” he told them. “We carry swords.”

Pompey’s enemies at Rome undermined his popularity by seeking the people’s support, declaring sympathy for the problems of citizens in financial trouble. By the 60s B.C.E., Rome’s urban population had soared to more than half a million. Hundreds of thousands of the poor lived crowded together in slum apartments, surviving on subsidized food distributions. Jobs were scarce. Danger haunted the streets because the city had no police force. Even many formerly wealthy property owners were in trouble: Sulla’s confiscations had caused land values to plummet and produced a credit crunch by flooding the real estate market with properties for sale.

The senators, jealous of Pompey’s glory, blocked his reorganization of the former Seleucid kingdom and his distribution of land to his army veterans. Pompey then negotiated with his fiercest political rivals, Crassus and Caesar (100–44 B.C.E.). In 60 B.C.E., they formed an unofficial arrangement called the First Triumvirate (“group of three”). Pompey forced through laws confirming his plans, reinforcing his status as a great patron. Caesar got the consulship for 59 B.C.E. and a special command in Gaul, where he could build his own client army. Crassus received financial breaks for the Roman tax collectors in Asia Minor, who supported him politically and financially.

This coalition of political rivals revealed how private relationships had largely replaced communal values in politics. To cement their political bond, Caesar arranged to have his daughter, Julia, marry Pompey in 59 B.C.E., even though she had been engaged to another man. Pompey soothed Julia’s jilted fiancé by offering the hand of his own daughter, who had been engaged to yet somebody else. Through these marital machinations, the two powerful antagonists now had a common interest: the fate of Julia, Caesar’s only daughter and Pompey’s new wife. (Pompey had earlier divorced his second wife after Caesar allegedly seduced her.) Pompey and Julia apparently fell deeply in love in their arranged marriage. As long as Julia lived, Pompey’s affection for her kept him from breaking his alliance with her father.

During the 50s B.C.E., Caesar won his soldiers’ loyalty with victories and plunder in Gaul, which he added to the Roman provinces. His political enemies in Rome dreaded his return, and the bond allying him to Pompey shattered in 54 B.C.E. when Julia died in childbirth. The two leaders’ rivalry exploded into violence: gangs of their supporters battled each other in Rome’s streets. The violence became so bad in 53 B.C.E. that it prevented elections. The First Triumvirate dissolved, and in 52 B.C.E. Caesar’s enemies convinced the Senate to make Pompey consul alone, breaking the republic’s long tradition of two consuls sharing power at the head of the state.

Civil war exploded when the Senate ordered Caesar to surrender his command. Like Sulla, Caesar led his army against Rome. In 49 B.C.E., when he crossed the Rubicon River, the official northern boundary of Italy, he uttered the famous words signaling there was now no turning back: “We have rolled the dice.” His troops and the people in the countryside cheered him on. He had many backers in Rome, with the masses counting on his legendary generosity for handouts and impoverished members of the elite hoping to regain their fortunes.

The support for Caesar convinced Pompey and most senators to flee to Greece. Caesar entered Rome peacefully, left soon thereafter to defeat enemies in Spain, and then sailed to Greece. There he nearly lost the war when his supplies ran out, but his soldiers stayed loyal even when they were reduced to eating bread made from roots. When Pompey saw what Caesar’s men were willing to live on, he cried, “I am fighting wild beasts.” Caesar defeated Pompey and the Senate at the battle of Pharsalus in central Greece in 48 B.C.E. Pompey fled to Egypt, where the pharaoh’s ministers treacherously murdered him.

Caesar then invaded Egypt, winning a difficult campaign that ended when he restored Cleopatra VII (69–30 B.C.E.) to the Egyptian throne. As ruthless as she was intelligent, Cleopatra charmed Caesar into sharing her bed and supporting her rule. Their love affair shocked the general’s friends and enemies alike: they thought Rome should seize power from foreigners, not share it with them.

By 45 B.C.E., Caesar had won the civil war. He apparently believed that only a sole ruler could end the chaotic violence of the factions, but the republic’s oldest tradition prohibited monarchy. So Caesar decided to rule as a king without the title, taking instead the traditional Roman title of dictator, used for a temporary emergency ruler. In 44 B.C.E., he announced he would continue as dictator without a term limit. “I am not a king,” he insisted. The distinction, however, was meaningless. As ongoing dictator, he controlled the government. Elections for offices continued, but Caesar manipulated the results by recommending candidates to the assemblies, which his supporters dominated.

As sole ruler, Caesar imposed a moderate cancellation of debts; a cap on the number of people eligible for subsidized grain; a large program of public works, including public libraries; colonies for his veterans in Italy and abroad; plans to rebuild Corinth and Carthage as commercial centers; and citizenship for more non-Romans. Caesar treated his opponents mildly, thereby obligating them to become his grateful clients. Caesar’s decision not to seek revenge earned him unheard-of honors, such as a special golden seat in the Senate house and the renaming of the seventh month of the year after him (July). He also regularized the Roman calendar by having each year include 365 days, a calculation based on an ancient Egyptian calendar that forms the basis for our modern one.

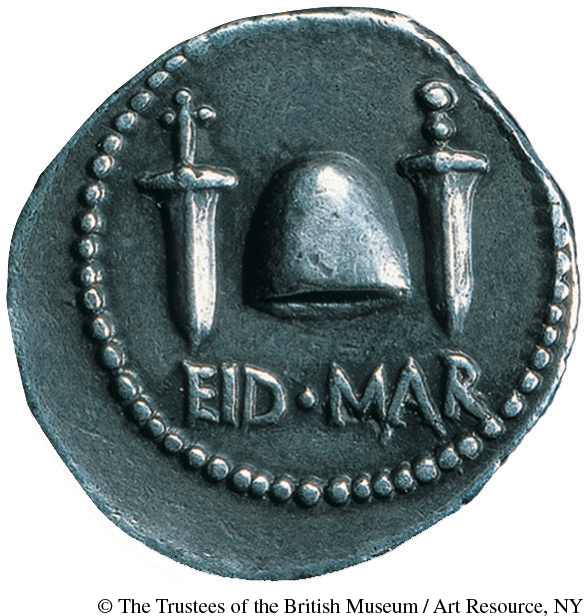

Caesar’s dictatorship satisfied the people but outraged the optimates. They resented being dominated by one of their own, a “traitor” who had deserted to the people’s faction. Some senators, led by Caesar’s former close friend Marcus Junius Brutus (85–42 B.C.E.), conspired to murder him. They stabbed Caesar repeatedly in the Senate house on March 15 (the Ides of March), 44 B.C.E. When Brutus struck him, Caesar gasped his last words—in Greek: “You, too, son?” He collapsed dead at the foot of a statue of Pompey.

REVIEW QUESTION What factors generated the conflicts that caused the Roman Republic’s destruction?

The liberators, as they called themselves, had no new plans for government. They apparently expected the republic to revive automatically after Caesar’s murder, ignoring the political violence of the past century and the deadly imbalance in Roman values, with “great men” placing their competitive private interests above the community’s well-being. The liberators were stunned when the people rioted at Caesar’s funeral to vent their anger against the upper class that had robbed them of their generous patron. Instead of then forming a united front, the elite resumed their personal vendettas. The traditional values of the republic failed to save it.