Polytheism and Christianity in Competition

Polytheism and Christianity in Competition

Polytheism and Christianity competed for people’s faith. They shared some similar beliefs. Both, for example, regarded spirits and demons as powerful and ever-present forces in life. Some polytheists focused their beliefs on a supreme god who seemed almost monotheistic; some Christians took ideas from Neoplatonist philosophy, which was based on Plato’s ideas about God and spirituality. (See “Seeing History: Changing Religious Beliefs: Pagan and Christian Sarcophagi.”)

Unbridgeable differences remained, however, between the beliefs of traditional polytheists and Christians. People disagreed over whether there was one God or many, and what degree of interest the divinity (or divinities) paid to the human world. Polytheists could not accept a divine savior who promised eternal salvation for believers but had apparently lacked the will or the power to overthrow Roman rule and prevent his own execution. The traditional gods by contrast, they believed, had given their worshippers a world empire. Moreover, polytheists could say, cults such as that of the goddess Isis and philosophies such as Stoicism insisted that only the pure of heart and mind could be admitted to their fellowship. Christians, by contrast, embraced sinners. Why, wondered perplexed polytheists, would anyone want to associate with such people? In short, as the Greek philosopher Porphyry argued, Christians had no right to claim they possessed the sole version of religious truth, for no one had ever discovered a doctrine that provided “the sole path to the liberation of the soul.”

The slow pace of Christianization revealed how strong polytheism remained in this period, especially at the highest social levels. In fact, the emperor known as Julian the Apostate (r. 361–363) rebelled against his family’s Christianity—the word apostate means “renegade from the faith”—by trying to reverse official support of the new religion in favor of his own less traditional and more philosophical interpretation of polytheism. Like Christians, he believed in a supreme deity, but he based his religious beliefs on Greek philosophy when he said, “This divine and completely beautiful universe, from heaven’s highest arch to earth’s lowest limit, is tied together by the continuous providence of god, has existed ungenerated eternally, and is imperishable forever.”

Emperors after Julian provided financial support for Christianity, dropped the title pontifex maximus, and stopped paying for sacrifices. Symmachus (c. 340–402), a polytheist senator who also served as prefect (mayor) of Rome, objected to the suppression of religious diversity: “We all have our own way of life and our own way of worship. . . . So vast a mystery cannot be approached by only one path.”

Christianity officially replaced polytheism as the state religion in 391 when Theodosius I (r. 379–395) enforced a ban on privately funded polytheist sacrifices. In 395, he also announced that all polytheist temples had to close. Nevertheless, some famous shrines, such as the Parthenon in Athens, remained open for a long time. Pagan temples were gradually converted to churches during the fifth and sixth centuries. Non-Christian schools were not forced to close—the Academy, founded by Plato in Athens in the early fourth century B.C.E., endured for 140 years more.

Jews posed a special problem for the Christian emperors. They seemed entitled to special treatment because Jesus had been a Jew. Previous emperors had allowed Jews to practice their religion, but the rulers now imposed legal restrictions. They banned Jews from holding office but still required them to assume the financial burdens of curials without the status. By the late sixth century, the law barred Jews from marrying Christians, making wills, receiving inheritances, or testifying in court.

These restrictions began the long process that turned Jews into second-class citizens in later European history, but they did not destroy Judaism. Magnificent synagogues had been built in Palestine, though most Jews had been dispersed throughout the cities of the empire and the lands to the east. Written Jewish teachings and interpretations proliferated in this period, culminating in the vast fifth-century C.E. texts known as the Palestinian and the Babylonian Talmuds (learned opinions on the Mishnah, a collection of Jewish law) and the Midrash (commentaries on parts of Hebrew Scripture).

As the official religion, Christianity attracted more believers, especially in the military. Soldiers could convert and still serve in the army. Previously, some Christians had felt a conflict between the military oath and their allegiance to Christ. Once the emperors were Christians, however, soldiers viewed military duty as serving Christ’s regime.

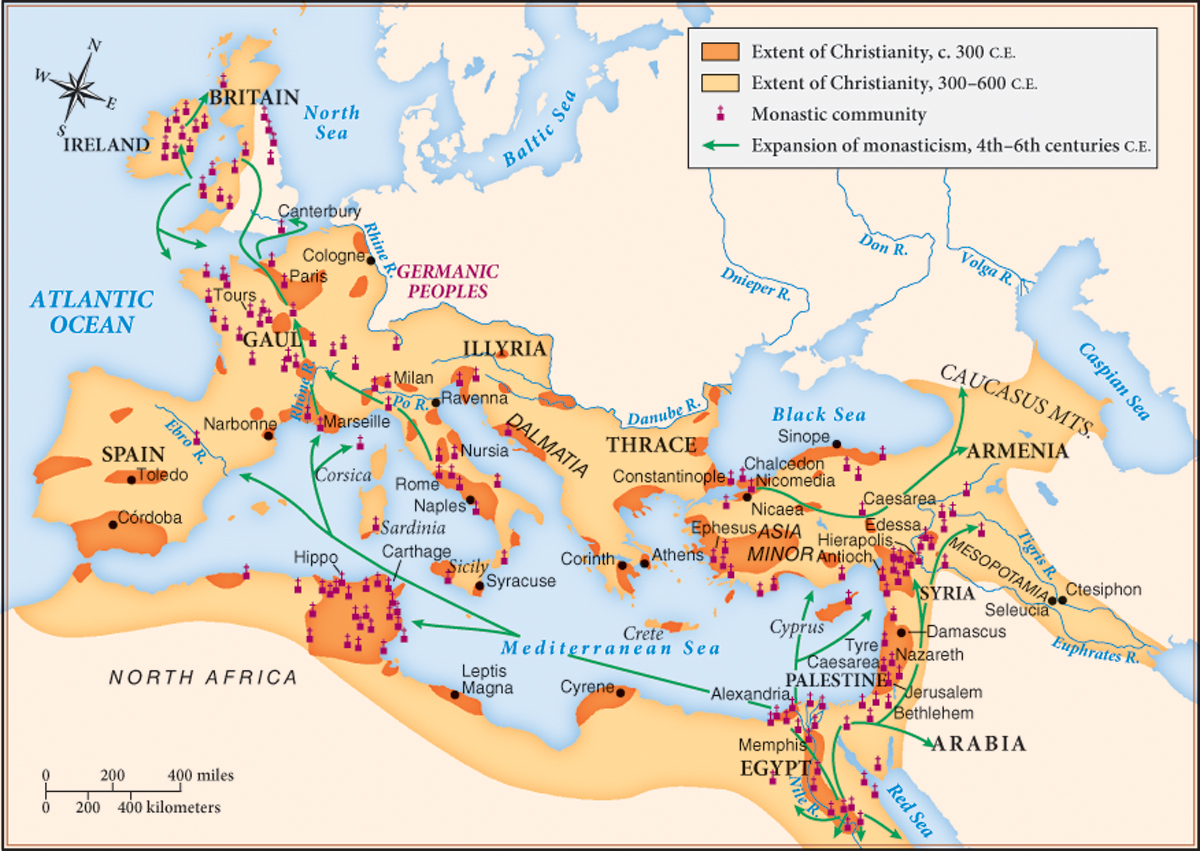

Christianity’s social values contributed to its appeal by offering believers a strong sense of shared identity and community. When Christians traveled, they could find a warm welcome in the local congregation (Map 7.2). The faith also won converts by promoting the tradition of charitable works characteristic of Judaism and some polytheist cults, which emphasized caring for poor people, widows, and orphans. By the mid-third century, Rome’s Christian congregation was supporting fifteen hundred widows and poor people.

Women were deeply involved in the new faith. Augustine (354–430), bishop of Hippo in North Africa and perhaps the most influential theologian in Western civilization, recognized women’s contribution to the strengthening of Christianity in a letter he wrote to the unbaptized husband of a baptized woman: “O you men, who fear all the burdens imposed by baptism! Your women easily best you. Chaste and devoted to the faith, it is their presence in large numbers that causes the church to grow.” Women could earn respect by giving their property to their congregation or by renouncing marriage to dedicate themselves to Christ. Consecrated virgins rejecting marriage and widows refusing to remarry joined donors of large amounts of money as especially admired women. Their choices challenged the traditional social order, in which women were supposed to devote themselves to raising families. Even these sanctified women, however, were largely excluded from leadership positions as the church’s hierarchy came more closely to resemble the male-dominated world of imperial rule. There were still some women leaders in the church even in the fourth century, but they were a small minority.

The hierarchy of male bishops replaced early Christianity’s relatively loose communal organization, in which women held leadership posts. Over time, the bishops replaced the curials as the emperors’ partners in local rule, taking control of the distribution of imperial subsidies to the people. Regional councils of bishops appointed new bishops and addressed doctrinal disputes. Bishops in the largest cities became the most powerful leaders in the church. The bishop of Rome eventually emerged as the church’s supreme leader in the western empire, claiming for himself a title previously applied to many bishops: pope (from pappas, a child’s word for “father” in Greek), the designation still used for the head of the Roman Catholic church. Christians in the eastern empire never conceded this title to the bishop of Rome.

The bishops of Rome claimed they had leadership over other bishops on the basis of the New Testament, where Jesus addresses Peter, his head apostle: “You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church. . . . I will entrust to you the keys of the kingdom of heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven. Whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matt. 16:18–19). Noting that Peter’s name in Greek means “rock” and that Peter had founded the Roman church, bishops in Rome eventually argued that they had the right to command the church as Peter’s successors.