The Emergence of Christian Monks

The Emergence of Christian Monks

Christian asceticism peaked with the emergence of monks: men and women who withdrew from everyday society to live a life of extreme self-denial imitating Jesus’s suffering, while praying for divine mercy on the world. In monasticism, monks originally lived alone, but soon they formed communities for mutual support in the pursuit of holiness.

Polytheists and Jews had strong ascetic traditions, but Christian monasticism was distinctive for the huge numbers of people drawn to it and the high status that they earned in the Christian population. Monks’ fame came from their rejection of ordinary pleasures and comforts. They left their families and congregations, renounced sex, worshipped almost constantly, wore rough clothes, and ate so little they were always starving. To achieve inner peace, monks fought a constant spiritual battle against fantasies of earthly delights—plentiful, tasty food and the joys of sex.

The earliest monks emerged in Egypt in the second half of the third century. Antony (c. 251–356), the son of a well-to-do family, was among the first to renounce regular existence. After hearing a sermon stressing Jesus’s command to a rich young man to sell his possessions and give the proceeds to the poor (Matt. 19:21), he left his property in about 285 and withdrew into the desert to devote the rest of his life to worshipping God through extreme self-denial.

The opportunity to gain fame as a monk seemed especially valuable after the end of the Great Persecution. Becoming a monk—a living martyrdom—not only served as the substitute for dying a martyr’s death but also emulated the sacrifice of Christ. In Syria, “holy women” and “holy men” sought fame through feats of pious endurance; Symeon (390–459), for example, lived atop a tall pillar for thirty years, preaching to the people gathered at the foot of his perch. Egyptian Christians came to believe that their monks’ supreme piety made them living heroes who ensured the annual flooding of the Nile (which enriched the soil, aiding agriculture), an event once associated with the pharaohs’ religious power.

In a Christian tradition originating with martyrs, the relics of dead holy men and women—body parts or clothing—became treasured sources of protection and healing. The power associated with the relics of saints (people venerated after their deaths for their holiness) gave believers faith in divine favor.

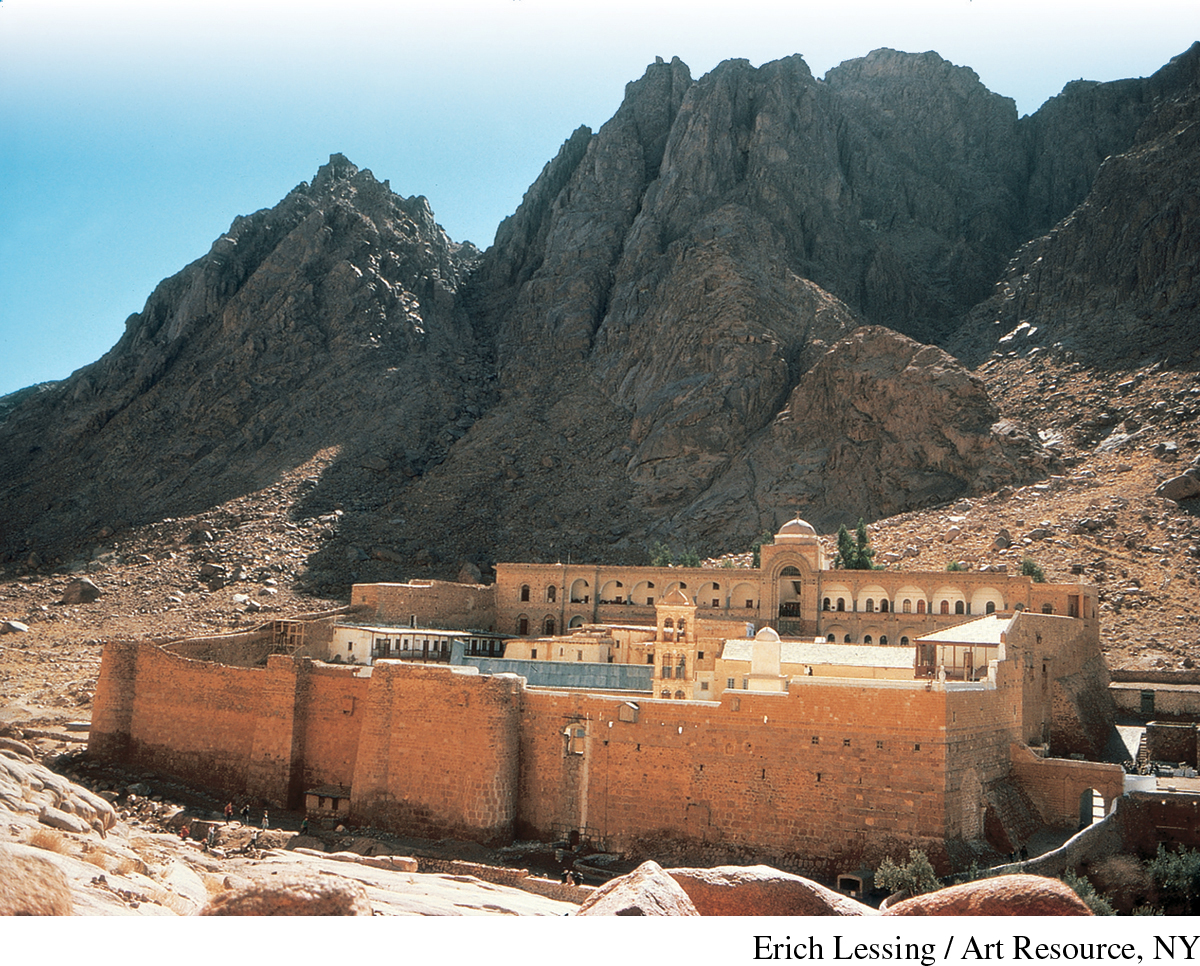

In about 323, an Egyptian Christian named Pachomius organized the first monastic community, establishing the tradition of single-sex settlements of male or female monks. This communal monasticism dominated Christian asceticism ever after. Communities of men and women were often built close together to share labor, with women making clothing, for example, while men farmed.

Some monasteries imposed military-style discipline, but there were large differences in the degree of control of the monks and the extent of contact allowed with the outside world. Some groups strove for complete self-sufficiency and strict rules to avoid transactions with outsiders. Basil of Caesarea (c. 330–379), in Asia Minor, started an alternative tradition of monasteries in service to society. Basil (later dubbed “the Great”) required monks to perform charitable deeds, especially ministering to the sick, a development that led to the foundation of the first hospitals, which were attached to monasteries.

A milder code of monastic conduct became the standard in the west beginning about 540. Called the Benedictine rule after its creator, Benedict of Nursia (c. 480–553), it mandated the monastery’s daily routine of prayer, scriptural readings, and manual labor. This was the first time in Greek and Roman history that physical work was seen as noble, even godly. The rule divided the day into seven parts, each with a compulsory service of prayers and lessons, called the office. Unlike the harsh regulations of other monastic communities, Benedict’s code did not isolate the monks from the outside world or deprive them of sleep, adequate food, or warm clothing. Although it gave the abbot (the head monk) full authority, it instructed him to listen to other members of the community before deciding important matters. He was not allowed to beat disobedient monks. Communities of women, such as those founded by Basil’s sister Macrina and Benedict’s sister Scholastica, generally followed the rules of the male monasteries, with an emphasis on the decorum thought necessary for women.

Monastic piety held special appeal for women and the rich because women could achieve greater status and respect for their holiness than ordinary life allowed them, and the rich could win fame on earth and hope for favor in heaven by endowing monasteries with large gifts of money. Jerome wrote, “[As monks,] we evaluate people’s virtue not by their gender but by their character, and judge those to be worthy of the greatest glory who have renounced both status and riches.” Some monks did not choose their life; monasteries took in children from parents who could not raise them or who, in a practice called oblation, gave them up to fulfill pious vows. Jerome once advised a mother regarding her young daughter:

Let her be brought up in a monastery, let her live among virgins, let her learn to avoid swearing, let her regard lying as an offense against God, let her be ignorant of the world, let her live the angelic life, while in the flesh let her be without the flesh, and let her suppose that all human beings are like herself.

When the girl reached adulthood as a virgin, he added, she should avoid the baths so that she would not be seen naked or give her body pleasure by dipping in the warm pools. Jerome emphasized traditional values favoring males when he promised that God would reward the mother with the birth of sons in compensation for the dedication of her daughter.

REVIEW QUESTION How did Christianity both unite and divide the Roman Empire?

Monasteries could come into conflict with the church leadership. Bishops resented members of their congregations who withdrew into monasteries, especially because they then gave money and property to their new community instead of to their local churches. Monks represented a threat to bishops’ authority because holy men and women earned their special status not by having it bestowed from the church hierarchy but through their own actions.