Non-Roman Migrations into the Western Roman Empire

Non-Roman Migrations into the Western Roman Empire

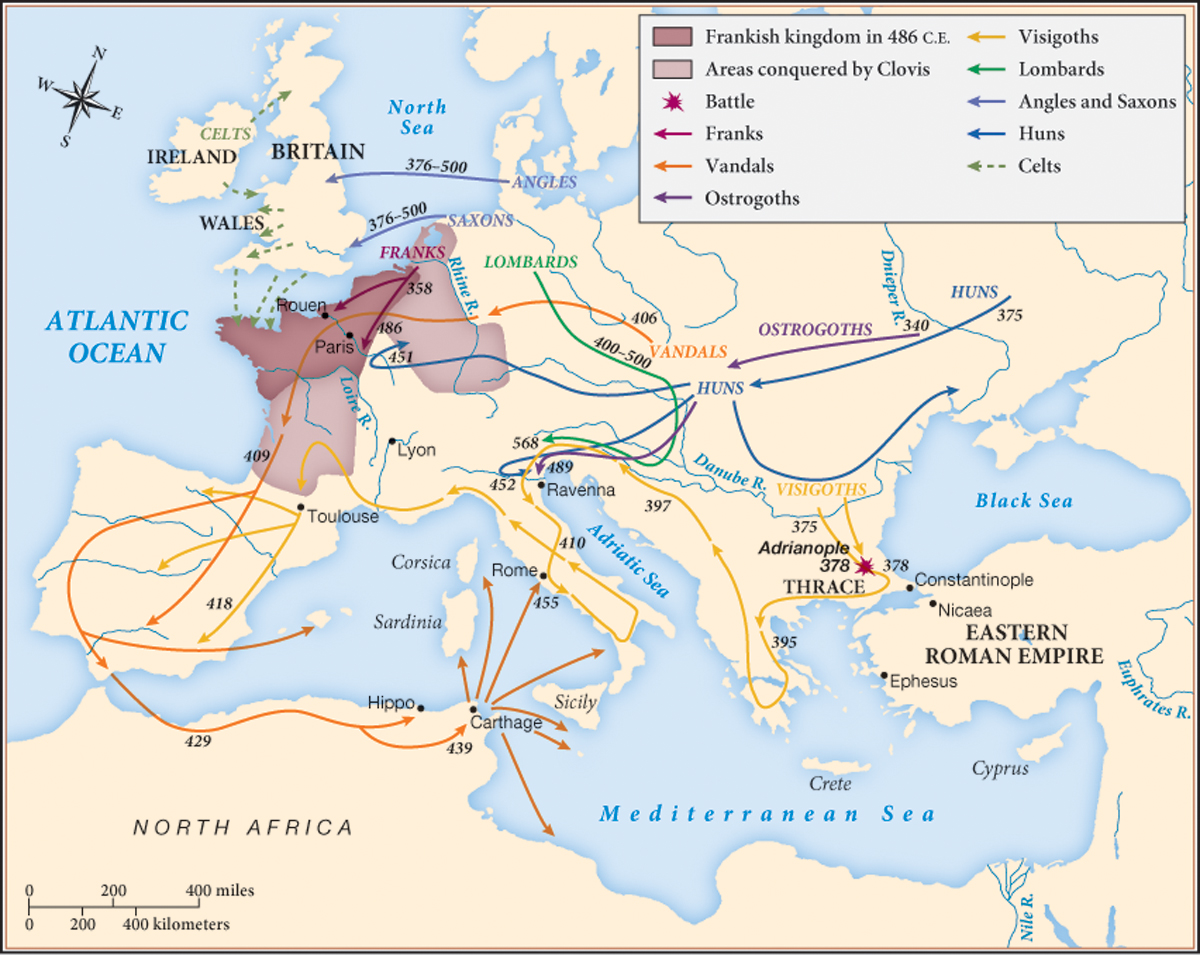

The non-Roman peoples who flooded into the empire had diverse origins; simply labeling them “Germanic peoples” misrepresents the diversity of their multiethnic languages and customs. These diverse barbarian peoples had no previously established sense of ethnic identity, and many of them had had long-term contact with Romans through trade across the frontiers and service in the Roman army. By encouraging this contact, the emperors unwittingly set in motion forces that they could not in the end control. By late in the fourth century, attacks by the Huns had destabilized life for these bands across the Roman frontiers, and the families of the warriors followed them into the empire seeking safety. Hordes of men, women, and children crossed into the empire as refugees, fleeing the Huns. They came with no political or military unity and no clear plan. They shared only their terror of the Huns and their custom of conducting raids for a living in addition to farming small plots.

The inability to prevent immigrants from crossing the border or to integrate them into Roman society once they had crossed put great stress on the western central government. Persistent economic weakness rooted in the third-century crisis worsened this pressure. Tenant farmers and landlords fleeing crushing taxes had left as much as 20 percent of farmland unworked in the most seriously affected areas. The loss of revenue made the government unable to afford enough soldiers to control the frontiers. Over time, the immigrating non-Roman peoples forced the Roman government to grant them territory in the empire. Remarkably, they then began to develop separate ethnic identities and create new societies for themselves and the Romans living under their control.

In their homelands the barbarians had lived in chiefdom societies, whose members could only be persuaded, not ordered, to follow the chief. Chiefs maintained their status by giving gifts to their followers and leading raids to capture cattle and slaves. They led clans—groups of households organized by kinship lines, following maternal as well as paternal descent. Violence against a fellow clan member was the worst possible offense. Clans in turn grouped themselves into tribes—fluctuating coalitions that anyone could join. Tribes differentiated themselves by their clothing, hairstyles, jewelry, weapons, religious cults, and oral stories.

Family life was patriarchal: men headed households and held authority over women, children, and slaves. Warfare preoccupied men, as their ritual sacrifices of weapons preserved in northern European bogs have shown. Women were valued for their ability to bear children, and rich men could have more than one wife and perhaps concubines as well. A division of labor made women responsible for growing crops, making pottery, and producing textiles, while men worked iron and herded cattle. Women enjoyed certain rights of inheritance and could control property, and married women received a dowry of one-third of their husband’s property.

Assemblies of free male warriors made major decisions in the tribes. Their leaders’ authority was restricted mostly to religious and military matters. Tribes could be unstable and prone to internal conflict—clans frequently feuded, with bloody consequences. Tribal law tried to determine what forms of violence were and were not acceptable in seeking revenge, but laws were oral, not written, and thus open to wide dispute. Tribes frequently attacked other tribes.

The migrations became a flood of people when the Huns invaded eastern Europe in the fourth century. The Huns arrived on the Russian steppes shortly before 370 as the vanguard of Turkish-speaking nomads moving west. Their warriors’ appearance terrified their victims, who reported their attackers had skulls elongated from having been bound between boards in infancy, faces grooved with decorative scars, and arms fearsome with elaborate tattoos. Huns excelled as raiders, launching cavalry attacks without warning. Skilled as horsemen, they could shoot their powerful bows accurately while riding full tilt and stay mounted for days, sleeping atop their horses and carrying snacks of raw meat between their thighs and the animal’s back.

By later in the fourth century the Huns had moved as far west as the Hungarian plain north of the Danube, terrifying the peoples there and launching raids southward into the Balkans. The emperors in Constantinople began paying the Huns to spare their territory, so the most ambitious Hunnic leader, Attila (r. c. 440–453), pushed his domain westward toward the Alps. He led his forces as far west as central France and into northern Italy. At Attila’s death in 453, the Huns lost their fragile unity and faded from history. By this time, however, the terror that they had inspired in the peoples living in eastern Europe had provoked the migrations that eventually transformed the western empire.

The first non-Roman group that created a new identity and society inside the empire were barbarians from the north. Their history illustrates the pattern of the migrations: desperate barbarians in barely organized groups with no uniform ethnic identity, who sought protection in the Roman Empire in return for military service but were brutalized, and then rebelled to form their own, new kingdom. Abused by the officers of the emperor Valens, these barbarians defeated and killed him at the battle of Adrianople in 378 (Map 7.3).

When the emperor Theodosius died in 395, the barbarians whom he had allowed to settle in the empire rebelled. United by the Gothic chief Alaric into a tribe known as the Visigoths, they fought their way into the western empire. In 410, they stunned the world by sacking Rome itself. For the first time since the Gauls eight hundred years before, a foreign force occupied the ancient capital. They terrorized the population: “What will be left to us?” the Romans asked when Alaric demanded all the citizens’ goods. “Your lives,” he replied.

Too weak to fend off the invaders, the western emperor Honorius in 418 reluctantly agreed to settle the newcomers in southwestern Gaul (present-day France), where they completed their unprecedented transition from tribe to kingdom, organizing a political state and creating their identity as Visigoths. They had no precedents to follow from their previous existence, so they adapted the only model available: Roman tradition, including a code of written law. The Visigoths established mutually beneficial relations with local Roman elites, who used time-tested ways of flattering their new superiors to gain advantages. Sidonius Apollinaris (c. 430–479), for example, a well-connected noble from Lyon, once purposely lost a backgammon game to the Visigothic king as a way of winning a favor.

How the new non-Roman kingdoms raised revenues is uncertain. Did the newcomers become landlords by forcing Roman property owners to redistribute a portion of their lands, slaves, and movable property as “ransom” to them? Or did Romans directly pay the expenses of the kingdom’s soldiers, who lived mostly in urban garrisons? Whatever the new arrangements were, the Visigoths found them profitable enough to expand into Spain within a century of establishing themselves in southwestern Gaul.

The western government’s concessions to the Visigoths led other groups to seize territory and create new kingdoms and identities. In 406, the Vandals cut a swath through Gaul all the way to the Spanish coast. (The modern word vandal, meaning “destroyer of property,” perpetuates their reputation for destruction.)

In 429, eighty thousand Vandals ferried to North Africa, where they broke their agreement to become federate allies with the western empire and captured the region. They crippled the western empire by seizing North Africa’s tax payments of grain and vegetable oil and disrupting the importation of food to Rome. They threatened the eastern empire with their navy and in 455 sailed to Rome, plundering the city. Back in the Roman province of Africa, the Vandals caused tremendous hardship for local people by confiscating property rather than allowing owners to make regular payments on the land. As Arian Christians, they persecuted North African Christians whose doctrines they considered heresy.

Small non-Roman groups took advantage of the disruption caused by bigger bands to break off distant pieces of the empire. The Anglo-Saxons, for example, were composed of Angles from what is now Denmark and Saxons from northwestern Germany. This mixed group invaded Britain in the 440s after the Roman army had been recalled from the province to defend Italy against the Visigoths. The Anglo-Saxons captured territory from the local Celtic peoples and the remaining Roman inhabitants. Gradually, their culture replaced the local traditions of the island’s eastern regions. The Celts there lost most of their language, and Christianity gave way to Anglo-Saxon beliefs except in Wales and Ireland. Another barbarian group, the Ostrogoths, carved out a kingdom in Italy in the fifth century. By the time their king Theodoric (r. 493–526) came to power, there had not been a western Roman emperor for nearly twenty years, and there never would be again.

The details of the change in the later fifth century that has traditionally, but simplistically, been called the fall of the Roman Empire reveal the complexity of the political transformation of the western empire under the new kingdoms. The weakness of the western emperors’ army had obliged them to hire foreign officers to lead the defense of Italy. By the middle of the fifth century, one non-Roman general after another had come to decide who would serve as a puppet emperor under his control.

The last such unfortunate puppet was only a child. His father, a former aide to Attila, tried to establish a royal house by proclaiming his young son as western emperor in 475. He gave the boy ruler the name Romulus Augustulus (“Romulus the Little Augustus”) to match his young age and to recall both Rome’s founder and its first emperor. In 476, following a dispute over pay, the boy emperor’s non-Roman soldiers murdered his father and deposed him. Little Augustus was given refuge and a pension. The rebels’ leader, Odoacer, had the Roman Senate petition Zeno, the eastern emperor, to recognize his leadership in return for his acknowledging Zeno as sole emperor over west and east. Odoacer thereafter oversaw Italy nominally as the eastern emperor’s subordinate, but he ruled on his own.

Theodoric established the Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy by eliminating Odoacer. He and his nobles wanted to enjoy the luxurious life of the empire’s elite and to preserve the empire’s prestige; they therefore left the Senate and consulships intact. An Arian Christian, Theodoric announced a policy of religious freedom. Like the other non-Romans, the Ostrogoths adopted and adapted Roman traditions that supported the stability of their own rule.

The Franks were especially significant in the reshaping of the western Roman Empire because they transformed Roman Gaul into Francia (from which comes the name France). In 507, their king Clovis (r. 485–511), with support from the eastern Roman emperor, overthrew the Visigothic king in Gaul. When the emperor named Clovis an honorary consul, Clovis celebrated this honor by having himself crowned with a diadem in the style of the emperors. He established western Europe’s largest new kingdom in what is today mostly France, overshadowing the neighboring and rival kingdoms of the Burgundians and Alemanni in eastern Gaul. Probably persuaded by his wife, Clotilda, a Christian, to believe that God had helped him defeat the Alemanni, Clovis proclaimed himself an orthodox Christian and renounced Arianism. To build stability, he carefully fostered good relations with the bishops as the regime’s intermediaries with the population.

Clovis’s dynasty, called Merovingian after the legendary Frankish ancestor Merovech, endured for another two hundred years, foreshadowing the kingdom that would emerge much later as the forerunner of modern France. The Merovingians survived so long because they successfully combined their own traditions of military bravery with Roman social and legal traditions. In addition, their location in far western Europe kept them out of the reach of the destructive invasions sent against Italy by the eastern emperor Justinian in the sixth century to reunite the Roman world.