The Preservation of Classical Traditions in the Late Roman Empire

The Preservation of Classical Traditions in the Late Roman Empire

Christianization of the late Roman Empire endangered the memory of classical traditions. The plays, histories, philosophical works, poems, speeches, and novels of classical Greece and Rome were polytheist and therefore potentially subversive of Christian belief, but the threat to their survival stemmed more from neglect than suppression. As many Christians became authors, their works displaced ancient Greek and Roman texts as the most important literature of the age.

Some classical texts survived, however, because Christian education and literature depended on non-Christian models, both Latin and Greek. Latin scholarship in the east received a boost when Justinian’s Italian wars caused Latin-speaking scholars to flee to Constantinople. There they helped conserve many ancient Roman texts. Scholars preserved classical literature because they regarded it as a crucial part of an elite education. Some knowledge of pre-Christian classics was required for a successful career in government service, the goal of every ambitious student. An imperial decree from 360 stated, “No person shall obtain a post of the first rank unless it shall be shown that he excels in long practice of liberal studies, and that he is so polished in literary matters that words flow from his pen faultlessly.”

Another factor promoting the preservation of classical literature was the use of classical rhetoric and its techniques for making persuasive arguments to present Christian theology. When Ambrose, bishop of Milan from 374 to 397, composed the first systematic description of Christian ethics for young ministers, he imitated the great Roman orator Cicero. Theologians refuted heresies among Christians by employing the dialogue form pioneered by Plato. Authors of the biographies of saints found inspiration in ancient literature that praised the heroes of traditional polytheist religion. Choricius, a Christian who held the official position of professor of rhetoric in Gaza, wrote works based on subjects from pre-Christian Greek mythology and history, such as the Trojan War or the Athenian general Miltiades. Similarly, Christian artists incorporated polytheist traditions in communicating their beliefs and emotions in paintings, mosaics, and carved reliefs. A favorite artistic motif of Christ with a sunburst surrounding his head, for example, took its inspiration from polytheist depictions of the radiant Sun as a god. (See the illustration on page 222.)

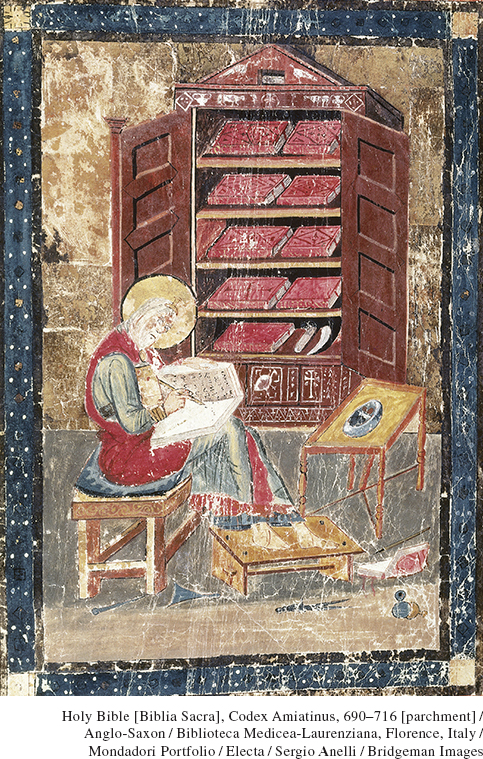

The growth of Christian literature generated a technological innovation that helped preserve classical literature. Polytheist scribes had written books on sheets of parchment (made from animal skin) or paper (made from papyrus). They then glued the sheets together and attached rods at both ends to form a scroll. Readers faced an awkward task in unrolling scrolls to read. For ease of use, Christians produced their literature in the form of the codex—a book with bound pages. Eventually the codex became the standard form of book production.

Despite its continuing importance in education and rhetoric, classical Greek and Latin literature barely survived the war-torn world dominated by Christians. Knowledge of Greek in the west faded so drastically that by the sixth century almost no one there could read the original versions of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the foundations of a classical literary education. Latin fared better, and scholars such as Augustine and Jerome knew Rome’s ancient literature extremely well. But they also saw its classics as potentially too seductive for a pious Christian because the pleasure that came from reading them could be a distraction from the worship of God. Jerome in fact once had a nightmare of being condemned on Judgment Day for having been more dedicated to Cicero than to Christ.

REVIEW QUESTION What policies did Justinian undertake to try to restore and strengthen the Roman Empire?

The closing around 530 of the Academy, founded in Athens by Plato more than nine hundred years earlier, demonstrated the dangers for classical learning in the later Roman Empire. This most famous of classical schools finally went out of business when many of its scholars emigrated to Persia to escape Justinian’s tightened restrictions on polytheist teachers and its revenues dwindled because the Athenian elite, its traditional supporters, were increasingly Christianized. The Neoplatonist school at Alexandria, by contrast, continued. Its leader John Philoponus (c. 490–570) was a Christian. In addition to Christian theology, Philoponus wrote commentaries on the works of Aristotle. Some of his ideas anticipated those of Galileo a thousand years later. He achieved the kind of synthesis of old and new that was one of the innovative outcomes of the cultural transformation of the late Roman world—he was a Christian subject of the eastern Roman Empire in sixth-century Egypt, heading a school founded long before by polytheists, studying the works of an ancient Greek philosopher as the inspiration for his forward-looking scholarship. The strong possibility that present generations could learn from the past would continue as Western civilization once again remade itself in medieval times.