Frankish Kingdoms with Roman Roots

Frankish Kingdoms with Roman Roots

The most important kingdoms in post-Roman Europe were Frankish. The Franks dominated Gaul during the sixth century, and by the seventh century their kingdoms roughly approximated the eastern borders of present-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg (Map 8.3). Moreover, the Frankish kings who constituted the Merovingian dynasty (c. 486–751) subjugated many of the peoples beyond the Rhine River, foreshadowing the contours of the western half of modern Germany.

Where there were cities, there were reminders of Rome. Elsewhere, the Roman heritage was less obvious. Imagine, then, travelers going from Rome to Trier (near what is now Bonn, Germany) in the early eighth century, perhaps to visit its bishop and check up on his piety. They would have relied on river travel: water routes were preferable to roads because land travel was slow, even though some Roman roads were still in fair repair, and because even large groups of travelers on the roads were vulnerable to attacks by robbers. Traveling northward on the Rhône River, our voyagers would have passed Roman walled cities and farmlands neatly and squarely laid out by Roman land surveyors. The great stone palaces of villas would still have dotted the countryside. Once at Trier, the travelers would have felt at home seeing the city’s great gate (now called the Porta Nigra), its monumental baths (some still standing today), and its cathedral, built on the site of a Roman palace. Being in Trier was almost like being in Rome. (See “Taking Measure: Papal Letters Sent from Rome to Northern Europe, c. 600–c. 700.”)

Nevertheless, these travelers would have noticed that the cities that they passed through were not what they had been in the heyday of the Roman Empire. True, cities still served as the centers of church administration. Bishops lived in them, and so did clergymen, servants, and others who helped the bishops. Cathedrals (the churches presided over by bishops) remained within city walls, and people were drawn to them for important rituals such as baptism. Nevertheless, many urban centers had lost their commercial and cultural vitality. Largely depopulated, they survived as skeletons of their former selves.

Whereas the chief feature of the Roman landscape had been cities, the Frankish landscape was characterized by dense forests, acres of marshes and bogs, patches of cleared farmland, and pastures for animals. These areas were not much influenced by Rome; they more closely represented the farming and village settlement patterns of the Franks.

On the vast plains between Paris and Trier, most peasants were only semi-free. They were settled in family groups on small holdings called manses, which included a house, a garden, and cultivable land. The peasants paid dues and sometimes owed labor services to a lord (an aristocrat who owned the land). Some of the peasants were descendants of the coloni (tenant farmers) of the late Roman Empire; others were the sons and daughters of slaves, now provided with a small plot of land; and a few were people of free Frankish origin who for various reasons had come down in the world. At the lower end of the social scale, the status of Franks and Romans had become identical.

Romans (or, more precisely, Gallo-Romans) and Franks had also merged at the elite level. Although people south of the Loire River continued to be called Romans and people to the north Franks, their cultures—their languages, their settlement patterns, their newly military way of life—were strikingly similar.

The language that aristocrats spoke and (often) read depended on location, not ethnicity. Among the many dialects in the Frankish kingdoms, some were Germanic, especially to the east and north, but most were derived from Latin, yet no longer the Latin of Cicero. At the end of the sixth century, the bishop Gregory of Tours (r. 573–c. 594), wrote, “Though my speech is rude, . . . to my surprise, it has often been said by men of our day, that few understand the learned words of the rhetorician but many the rude language of the common people.” This beginning to Gregory’s Histories, a valuable source for the Merovingian period, testifies to Latin’s transformation; Gregory expected that his “rude” Latin—the plain Latin of everyday speech—would be understood and welcomed by the general public.

The Frankish elites, like Frankish peasants, tended to live in the countryside rather than in cities. In fact, peasants and aristocrats tended to live together in villages. In many cases, a village consisted of a large central building (probably for the aristocratic household to use), sometimes with stone foundations. Surrounding the central building were smaller buildings, some of which were houses for peasant families, who lived with their livestock. Such villages might boast populations a bit over a hundred.

The elites of the Merovingian period cultivated military—rather than civilian—skills. They went on hunts and wore military-style clothing: the men wore trousers, a heavy belt, and a long cloak; both men and women bedecked themselves with jewelry. As hardened warriors, or wanting to appear so, aristocrats no longer lived in grand villas, choosing instead modest wooden structures without baths or heating systems. That explains why the village great house and the smaller ones nearby looked very much alike.

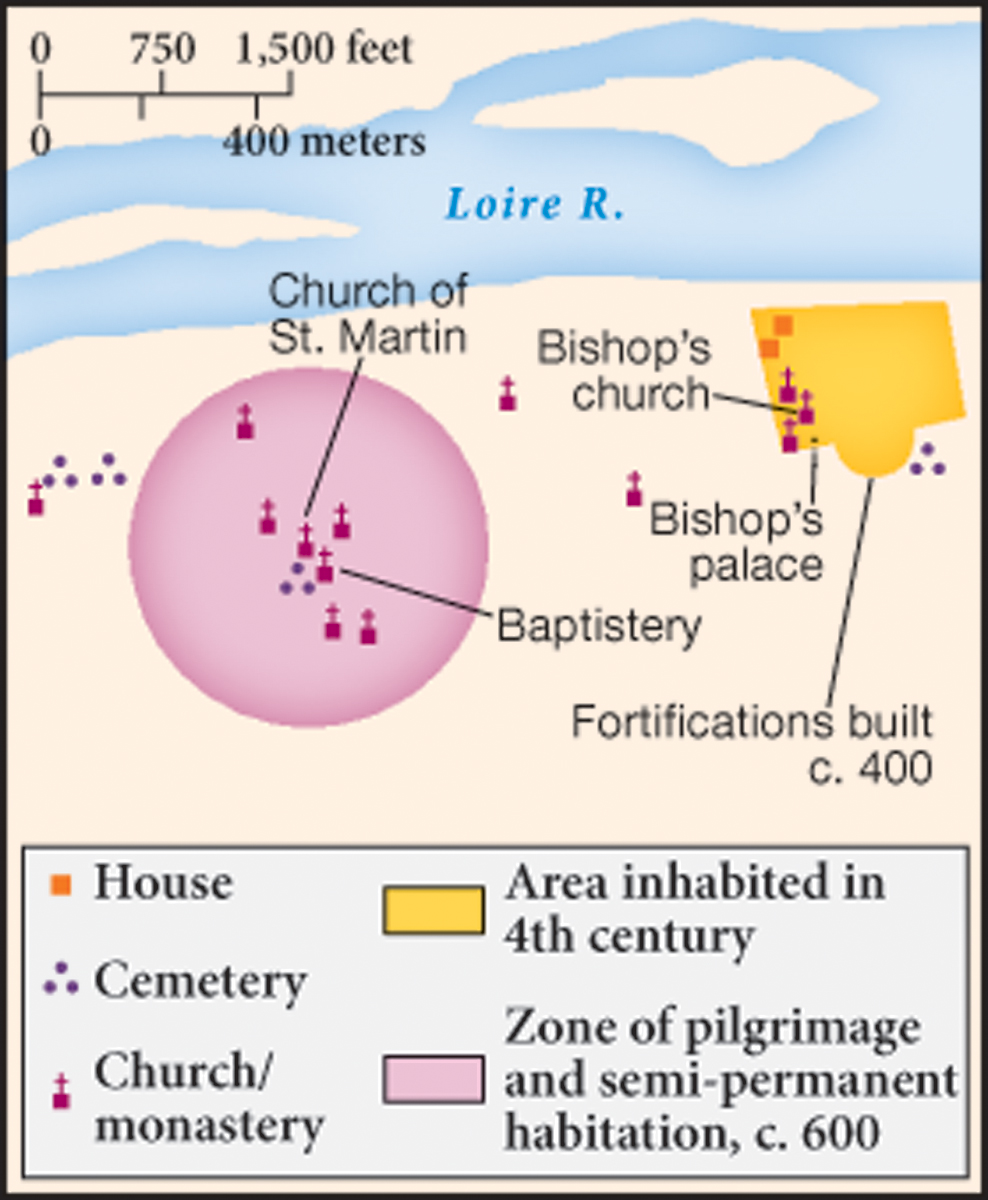

Sometimes villages formed around old villas. In other instances they clustered around sacred sites. Tours—where Gregory was bishop—exemplified this new-style settlement. In Roman times, Tours was a thriving city; around 400, its population diminished, and it constructed walls around its shrunken perimeter. By Gregory’s day, however, it had gained a new center outside the city walls. There a church had been built to house the remains of the most important and venerated person in the locale: St. Martin. This fourth-century soldier-turned-monk was long dead, but his relics remained at Tours, where he had served as bishop. The population of the surrounding countryside was pulled to his church as if to a magnet. Seen as a miracle worker, Martin acted as the representative of God’s power: a protector, healer, and avenger. In Gregory’s view, Martin’s relics (or rather God through Martin’s relics) not only cured the lame and sick but even prevented armies from plundering local peasants.

The veneration of saints and their relics marked a major departure from practices of the classical age, in which the dead had been banished from the presence of the living. In the medieval world, the holy dead held the place of highest esteem. The church had no formal procedures for proclaiming saints in the early Middle Ages, but holiness was “recognized” by influential local people and the local bishop. Everyone at Tours recognized Martin as a saint, and to tap into the power of his relics, the local bishop built a church directly over his tomb. For a man like Gregory of Tours and his flock, the church building was above all a home for the relics of the saints.