The Caliphs, Muhammad’s Successors, 632–750

The Caliphs, Muhammad’s Successors, 632–750

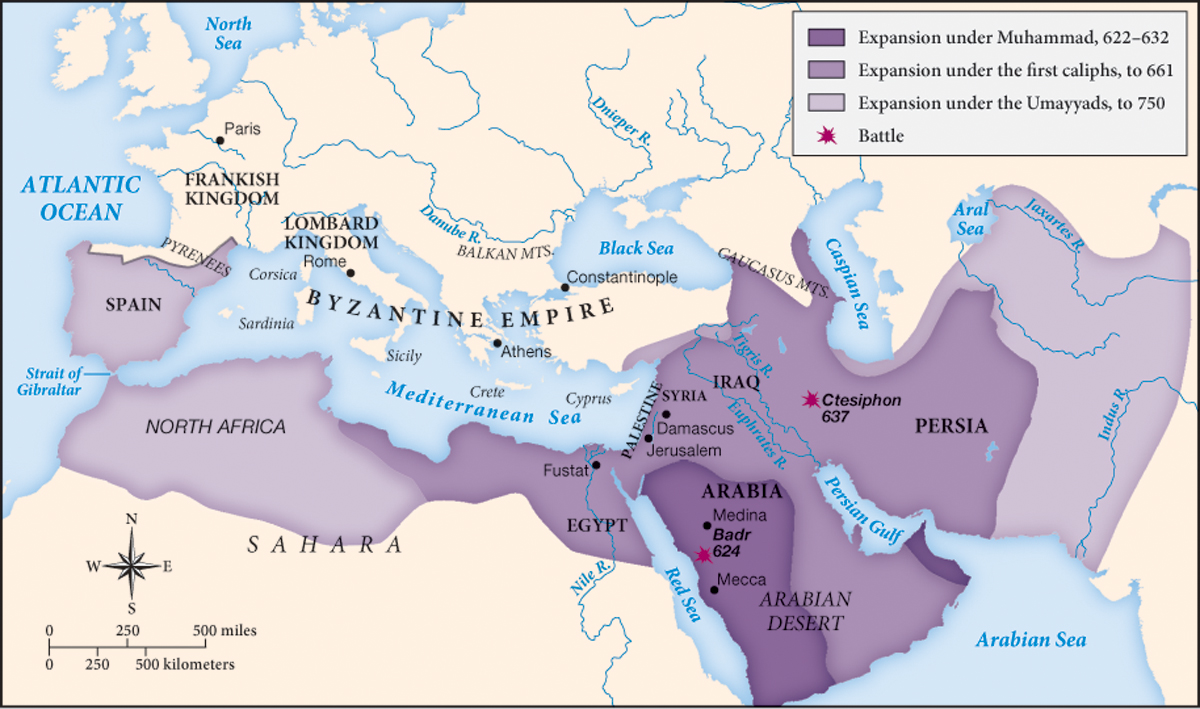

In the new political community he founded in Arabia, Muhammad reorganized traditional Arab society by cutting across clan allegiances and welcoming converts from every tribe. He forged the Muslims into a formidable military force, and his successors, the caliphs, took the Byzantine and Persian worlds by storm. They quickly conquered Byzantine territory in Syria and Egypt and invaded the Sasanid Empire, conquering the whole of Persia by 651 (Map 8.1). During the last half of the seventh century and the beginning of the eighth, Islamic warriors extended their sway westward to Spain and eastward to India.

How were such widespread conquests possible, especially in so short a time? First, the Islamic forces came up against weakened empires. The Byzantine and Sasanid states were exhausted from fighting each other. Second, discontented Christians and Jews welcomed Muslims into both Byzantine and Persian territories. The Monophysite Christians in Syria and Egypt, for example, had suffered persecution under the Byzantines and were glad to have new, Islamic overlords. There were also internal reasons for Islam’s success. Inspired by jihad, Arab fighters were well prepared: fully armed and mounted on horseback, using camel convoys to carry supplies and provide protection, they conquered with amazing ease. To secure their victories, they built garrison cities from which their soldiers requisitioned taxes and goods. (See “Document 8.2: The Pact of Umar.”)

Yet the solidarity of the Muslim community was threatened by disputes over the successors to Muhammad, the caliphs. While the first two caliphs came to power without serious opposition, the third, Uthman (r. 644–656), a member of the Umayyad clan and son-in-law of Muhammad, aroused discontent among other members of the inner circle and soldiers unhappy with his distribution of high offices and revenues. Accusing Uthman of favoritism, they supported his rival, Ali, a member of the Hashim clan (to which Muhammad had belonged) and the husband of Muhammad’s only surviving child, Fatimah. After a group of discontented soldiers murdered Uthman, civil war broke out between the Umayyads and Ali’s faction. It ended when Ali was killed by one of his own former supporters, and the caliphate remained in Umayyad hands from 661 to 750.

Despite defeat, the Shi‘at Ali (“Ali’s faction”) did not fade away. Ali’s memory lived on among Shi‘ite Muslims, who saw in him a symbol of justice and righteousness. For them, Ali’s death was the martyrdom of the true successor to Muhammad. They remained faithful to his dynasty, shunning the mainstream caliphs of Sunni Muslims (whose name derived from the word sunna, the practices of Muhammad). They awaited the arrival of the true leader—the imam—who in their view could come only from the house of Ali.