Land and Power

Land and Power

The Carolingian economy, based on war profits, trade, and agriculture, contributed first to the rise and then to the dissolution of the Carolingian Empire. After the spoils of war ceased to pour in, the Carolingians still had access to money and goods. To the north, the Carolingian economy intermingled with that of the Abbasid caliphate. Silver from the Islamic world probably came north up the Volga River through Kievan Rus to the Baltic Sea. There the coins were melted down and the silver was traded to the Carolingians in return for wine, jugs, glasses, and other manufactured goods. The Carolingians turned the silver into coins of their own, to be used throughout the empire for small-scale local trade. The weakening of the Abbasid caliphate in the mid-ninth century, however, disrupted this far-flung trade network and contributed to the weakening of the Carolingians at about the same time.

Land provided the most important source of Carolingian wealth and power. Carolingian aristocrats held many estates, called manors, scattered throughout the Frankish kingdoms and organized for production. The names of the peasants who tilled the soil and the dues and services they owed were even sometimes carefully noted down in registers.

A typical manor was Villeneuve Saint-Georges, which belonged to the monastery of Saint-Germain-des-Près (today in Paris) in the ninth century. Villeneuve consisted of arable fields, vineyards, meadows where animals could roam, and woodlands, all scattered about the countryside rather than connected in a compact unit. Peasant families did the farming. Each family had its own manse, which consisted of a house, a garden, and small sections of the arable land. Besides farming the land that belonged to them, the families also worked the demesne, the very large manse of the lord, in this case the abbey of Saint-Germain. Grown children would found their own families, and their parents’ land would be subdivided to give them a share. In many ways, the peasant household of the Carolingian period was the precursor of the modern nuclear family.

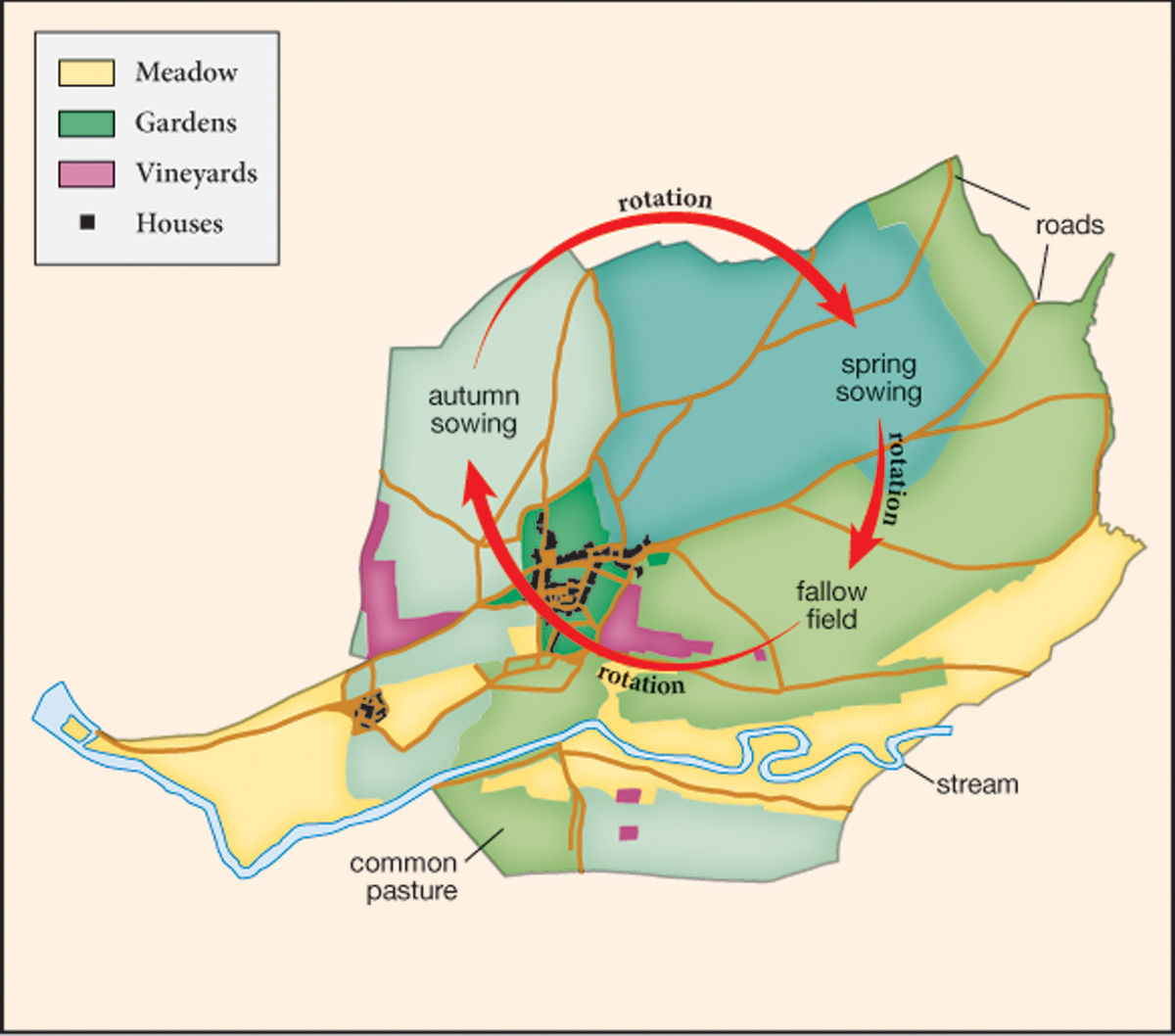

Peasants at Villeneuve practiced the most progressive sort of plowing, known as the three-field system, in which they farmed two-thirds of the arable land at one time (see Figure 9.1). They planted one-third of the arable land in the fall with winter wheat, one-third in the spring with summer crops, and left the remaining third fallow to restore its fertility. The crops sown and the fallow field then rotated so that land use was repeated only every three years. This method of organizing the land produced larger yields (because two-thirds of the land was cultivated each year) than the still-prevalent two-field system, in which only half of the arable land was cultivated one year while the other half lay fallow.

All the peasants at Villeneuve were dependents of the monastery and owed dues and services to Saint-Germain. Their status and obligations varied enormously. One family, for example, owed four silver coins, wine, wood, three hens, and fifteen eggs every year, and the men had to plow the fields of the demesne. Another family owed the intensive labor of working the vineyards. Peasant women spent much time at the lord’s house in the gynaeceum—the workshop where women made and dyed cloth and sewed garments—or in the kitchens, as cooks. Peasant men spent most of their time in the fields.

Manors organized on the model of Villeneuve were profitable. Like other lords, the Carolingians benefited from their extensive landholdings. Nevertheless, farming was still too primitive to return great surpluses, and as the lands belonging to the king were divided up in the wake of the partitioning of the empire and new invasions, the Carolingians’ dependence on manors scattered throughout their kingdom proved to be a source of weakness.