Emperors and Kings in Central and Eastern Europe

Emperors and Kings in Central and Eastern Europe

In contrast to the development of territorial lordships in France, Germany’s fragmentation had hardly begun before it was reversed. In the late Carolingian period, five large duchies (regions dominated by dukes) emerged in Germany. When the last Carolingian king in Germany died, in 911, the dukes elected one of themselves as king. Then, as the Magyar invasions increased, the dukes gave the royal title to the duke of Saxony, Henry I (r. 919–936), who proceeded to set up fortifications and reorganize his army, crowning his efforts with a major defeat of a Magyar army in 933.

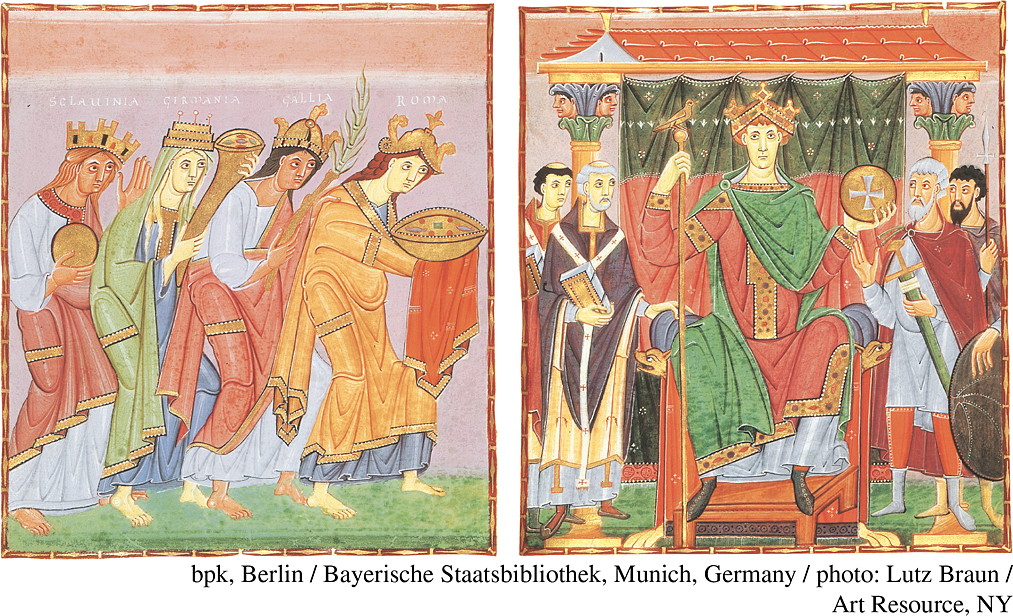

Otto I (r. 936–973), the son of Henry I, was an even greater military hero. In 951, he marched into Italy and took the Lombard crown. His defeat of the Magyar forces in 955 at Lechfeld gave him prestige and helped solidify his dynasty. Against the Slavs, with whom the Germans shared a border, Otto created marches (border regions specifically set up for defense) from which he could make expeditions and stave off counterattacks. After the pope crowned him emperor in 962, Otto claimed the Middle Kingdom carved out by the Treaty of Verdun and cast himself as the agent of Roman imperial renewal. His kingdom was called the Empire, as if it were the old Roman Empire revived. Some historians call it the Holy Roman Empire to distinguish it from the Roman Empire, but Otto and his successors made no such distinction; they considered it a continuation. In this book, it will be called the Empire.

Otto’s victories brought tribute and plunder, ensuring him a following but also raising the German nobles’ expectations for enrichment. The Ottonian kings—including Otto I and his successors Otto II (r. 973–983) and Otto III (r. 983–1002)—were not always able or willing to provide the gifts and inheritances their family members and followers expected. They did not divide their kingdom among their sons; instead, like castellans in France, they created a patrilineal pattern of inheritance. As a consequence, younger sons and other potential heirs felt cheated, and disgruntled royal kin led revolt after revolt against the Ottonian kings.

Relations between the Ottonians and the German clergy were more harmonious. Otto I appointed bishops, gave them extensive lands, and subjected the local peasantry to their overlordship. Like Charlemagne, Otto believed that the well-being of the church in his kingdom depended on him. The Ottonians gave bishops the right to collect revenues and call men to arms. Answering to the king and furnishing him with troops, the bishops became royal officials, while also carrying out their religious duties. German kings claimed the right to select bishops, even the pope at Rome, and to “invest” them (install them in their office) by participating in the ceremony that made them bishops.

Like all strong rulers of the day, the Ottonians presided over a renaissance of learning. They brought learned churchmen to court to write and teach. To an extent unprecedented elsewhere, noblewomen in Germany also acquired an education and participated in the intellectual revival. Living at home with their kinfolk and servants or in convents that provided them with comfortable private apartments, noblewomen wrote books and supported other artists and scholars.

Despite their military and political strength, the kings of Germany faced resistance from dukes and other powerful princes, who hoped to become regional rulers themselves. The Salians, the dynasty that succeeded the Ottonians, tried to balance the power among the German dukes but could not meld them into a corps of vassals the way the Capetian kings tamed their counts. In Germany, vassalage was considered beneath the dignity of free men. Instead of relying on vassals, the Salian kings and their bishops used ministerials (specially designated men who were legally serfs) to collect taxes, administer justice, and fight on horseback. Ministerials retained their servile status even though they often rose to wealth and high position. Under the Salian kings, ministerials became the mainstay of the royal army and administration.

Hand in hand with the popes, German kings created new, Catholic polities along their eastern frontier. The Czechs, who lived in the region of Bohemia, converted under the rule of Václav (r. 920–929), who thereby gained recognition in Germany as the duke of Bohemia. He and his successors did not become kings, remaining politically within the German sphere. Václav’s murder by his younger brother made him a martyr and the patron saint of Bohemia, a symbol around which later movements for independence rallied.

The Poles gained a greater measure of independence than the Czechs. In 966, Mieszko I (r. 963–992), the leader of the Slavic tribe known as the Polanians, accepted baptism to forestall the attack that the Germans were already mounting against pagan Slavic peoples along the Baltic coast and east of the Elbe River. Busily engaged in bringing the other Slavic tribes of Poland under his control, Mieszko adroitly shifted his alliances with various German princes to suit his needs. In 991, he placed his realm under the protection of the pope, establishing a tradition of Polish loyalty to the Roman church. Mieszko’s son Boleslaw the Brave (r. 992–1025) greatly extended Poland’s boundaries, at one time or another holding sway from the Bohemian border to Kiev. In 1000, he gained a royal crown with papal blessing.

Hungary’s case was similar to that of Poland. As we have seen, the Magyars settled in the region known today as Hungary. Under Stephen I (r. 997–1038), they accepted Roman Christianity. According to legend, the crown placed on Stephen’s head at his coronation (in late 1000 or early 1001) was sent to him by the pope. Stephen was canonized in 1083, and to this day the crown of St. Stephen remains the most hallowed symbol of Hungarian nationhood.

REVIEW QUESTION After the dissolution of the Carolingian Empire, what political systems developed in western, northern, eastern, and central Europe, and how did these systems differ from one another?

Symbols of rulership such as crowns, consecrated by Christian priests and accorded a prestige almost akin to saints’ relics, were among the most vital sources of royal power in central Europe. The economic basis for the power of central European rulers was largely agricultural. As happened elsewhere, here, too, centralized rule gradually gave way to regional rulers.