England: Unity through Common Law

England: Unity through Common Law

In the mid-twelfth century, the government of England was by far the most institutionalized in Europe. The king hardly needed to be present: royal government functioned smoothly without him, since officials handled all the administrative matters and record keeping. The very circumstances of the English king favored the growth of an administrative staff—the king’s frequent travels to and from the European continent meant that officials needed to work in his absence, and his enormous wealth meant that he could afford them.

Henry II (r. 1154–1189) was the driving force in extending and strengthening the institutions of English government. He took the throne in the wake of a terrible civil war (1139–1153) between two royal claimants. The chaos had benefited the English barons and high churchmen, who gained new privileges and powers as the monarch’s authority waned. Newly built private castles, already familiar on the continent, now appeared in England as symbols of the rising power of the English barons. But when Henry was crowned king of England, ushering in the Angevin (from Anjou) dynasty there, he reversed the trend.*

Even beyond England, Henry had enormous power. His marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152, after her marriage to Louis VII of France was annulled, brought the enormous inheritance of the duchy of Aquitaine to the English crown. Although Henry was technically the vassal of the king of France for his continental lands, he effectively ruled a territory that stretched from England to southern France (Map 11.1).

Eleanor gave Henry not only an enormous inheritance but also the sons he needed to maintain his dynasty. He gave her much less. As queen of France, Eleanor had enjoyed an important position: she disputed with St. Bernard, the Cistercian abbot who was the most renowned churchman of the day, and when she accompanied Louis on the Second Crusade, she brought more troops than he did. Of independent mind, she determined to separate from Louis even before he considered leaving her. But with Henry, she lost much of her power, for he dominated her just as he came to dominate his barons. Turning to her offspring in 1173, Eleanor, disguised as a man, tried to join her eldest son, Henry the Younger, in a plot against his father. But the rebellion was put down, and she spent most of her years thereafter, until her husband’s death in 1189, confined under guard at Winchester Castle. (In death, however, she gained dignity, with her tomb next to Henry’s.)

As soon as Henry II became king of England, he destroyed or confiscated the new castles and regained crown land. Then he proceeded to extend monarchical power, above all by imposing royal justice. His judicial reforms built on an already well-developed legal system. The Anglo-Saxon kings had royal district courts: the king appointed sheriffs to police the shires, muster military levies, and haul criminals into court. The Norman kings retained these courts and had the right to summon large landowners in the shire to attend them. To these established institutions, Henry II added a system of judicial visitations called eyres (from the Latin iter, “journey”). Under this system, royal justices made regular trips to every locality in England to judge those accused of murder, arson, or rape—all defined as crimes against the “king’s peace.” The justices summoned representatives of the knightly class to meet and either give the sheriff the names of those suspected of committing crimes in the vicinity or arrest the suspects themselves and hand them over to the royal justices.

During the eyres, the justices also heard cases between individuals, today called civil cases. Free men and women (that is, people of the knightly class or above) could bring their disputes over such matters as inheritance, dowries, and property claims to the king’s justices. Earlier courts had generally relied on duels between litigants to determine verdicts. Henry’s new system offered a different option, an inquest under royal supervision.

The new system of common law—law that applied to all of England—was praised for its efficiency, speed, and conclusiveness in a twelfth-century legal treatise known as Glanvill (after its presumed author). Glanvill might have added that the king also speedily gained a large treasury. The exchequer, as the financial bureau of England was called, recorded all the fines paid for judgments and the sums collected for writs. The amounts, entered on parchment sewn together and stored as rolls, became the Receipt Rolls and Pipe Rolls, the first of many such records of the English monarchy and an indication that writing had become a mechanism for institutionalizing royal power in England.

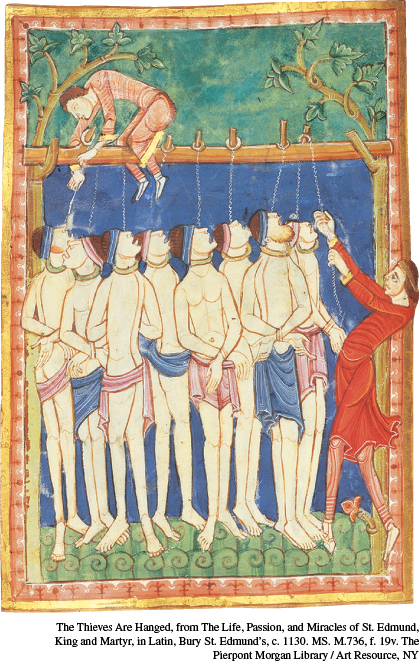

The stiffest opposition to Henry’s extension of the royal courts came from the church, where a separate system of trial and punishment had long been available to the clergy and to others who enjoyed church protection. The punishments for crimes meted out by church courts were generally quite mild. Protective of their special status, churchmen refused to submit to the jurisdiction of Henry’s courts. Henry insisted, and the ensuing contest between Henry II and his archbishop, Thomas Becket (1118–1170), became the greatest battle between the church and the state in the twelfth century. The conflict simmered for six years, with Becket refusing to allow “criminous clerics”—clergy suspected of committing a crime—to come before royal courts. Then Henry’s henchmen murdered Becket, right in his own cathedral. The desecration unintentionally turned Becket into a martyr. Henry was forced by a general public outcry to do penance for the deed. In the end, both church and royal courts expanded to address the concerns of an increasingly litigious society.

In England, Henry II made the king’s presence felt everywhere through his system of traveling royal courts. On the continent, he maintained his position through a combination of war and negotiation. He bequeathed to his sons Richard I (r. 1189–1199) and John (r. 1199–1216) an omnipresent and wealthy monarchy. Its omnipresence derived largely from its eyre system of justice and its administrative apparatus. Its wealth came from court fees, income from numerous royal estates both in England and on the continent, taxes from cities, and customary feudal dues (reliefs and aids) collected from barons and knights. Enriched by the commercial economy of the late twelfth century, the English kings encouraged their knights and barons not to serve them personally in battle but, in lieu of service, to pay the king a tax called scutage. The monarchs preferred to hire mercenaries both as troops to fight external enemies and as police to enforce the king’s will at home.

Richard I, known as the Lion-Hearted, went on the Third Crusade the very year he was crowned. On his way home, he was captured and held for ransom by political enemies for a long time; he died soon thereafter while defending his possessions on the continent. His successor, John, lived longer but gained no admiring epithet. In fact, he presided over the whittling away of the English empire. In 1204, the king of France confiscated the northern French territories held by John. Between 1204 and 1214, John did everything he could to add to the crown revenues so that he could pay for an army to win back the territories. He forced his vassals to pay ever-increasing scutages, and he extorted money in the form of new feudal dues. He compelled the widows of his vassals either to marry men of his choosing or to pay him a hefty fee. Despite John’s heavy investment in the war, his army was defeated in 1214 at the battle of Bouvines. The defeat caused discontented English barons to rebel openly against the king. At Runnymede in June 1215, John was forced to agree to the charter of baronial liberties that has come to be called Magna Carta (“Great Charter”).

The English barons intended Magna Carta to be a conservative document defining the “customary” obligations and rights of the nobility and forbidding the king to break from these customs without consulting his barons. It maintained that all free men in the land had certain rights that the king was obligated to uphold. In this way, Magna Carta implied that the king was not above the law. In time, as the definition of free men expanded to include all the king’s subjects, Magna Carta came to be seen as a guarantee of the rights of Englishmen (and eventually Englishwomen) in general. (See “Contrasting Views: Magna Carta.”)