The Troubadours: Poets of Love and Play

The Troubadours: Poets of Love and Play

Already at the beginning of the twelfth century, Duke William IX of Aquitaine (1071–1126), the grandfather of Eleanor of Aquitaine, had written lyric poems in Occitan, the vernacular of southern France. Perhaps influenced by Arabic and Hebrew love poetry from al-Andalus, he was the first of the troubadours, lyric poets who wrote in Occitan. (Women poets using this language were known as trobairitz.) Their poems were clever and inventive. The final four-line stanza of one such poem demonstrates the poet’s skill:

|

Per aquesta fri e tremble, |

For this one I shiver and tremble, |

|

quar de tan bon’ amor l’am; |

I love her with such a good love; |

|

qu’anc no cug qu’en nasques semble |

I do not think the like of her was ever born |

|

en semblan de gran linh n’Adam. |

in the long line of Lord Adam. |

The rhyme scheme of this poem appears to be simple—tremble goes with semble, l’am with n’Adam—but the entire poem has five earlier verses, all six lines long and all containing the -am, -am rhyme in the fourth and sixth lines, while every other line within each verse rhymes as well.

Troubadours and trobairitz varied their rhymes and meters endlessly to dazzle their audiences with brilliant originality. Their most common topic, love, echoed the twelfth-century church’s emphasis on the emotional relationship between God and humans. But the troubadours concentrated on the various forms of human love and its joys and sorrows. Thus the trobairitz Contessa de Dia (flourished c. 1160) wrote about her unrequited love for a man:

So bitter do I feel toward him

whom I love more than anything.

With him my mercy and cortesia [fine manners] are in vain.

The key to these lines, as to troubadour verse in general, is the idea of cortesia. The word refers to courtesy (the refinement of people living at court) and to the struggle to achieve an ideal of virtue.

Historians and literary critics used to use the term courtly love to emphasize one of the themes of this literature: overwhelming love for a beautiful married noblewoman who is far above the poet in status and utterly unattainable. But this theme was only one of many aspects of love that the troubadours sang about: some of the songs boasted of sexual conquests, others played with the notion of equality between lovers, and still others preached that love was the source of virtue. The real overall theme of this literature is not courtly love; it is the power of women. And no wonder: there were many powerful ladies (the female counterparts of lords) in southern France. They owned property, had vassals, led battles, decided disputes, and entered into and broke political alliances as their advantage dictated. Both men and women appreciated troubadour poetry, which recognized and praised women’s power even as it eroticized it.

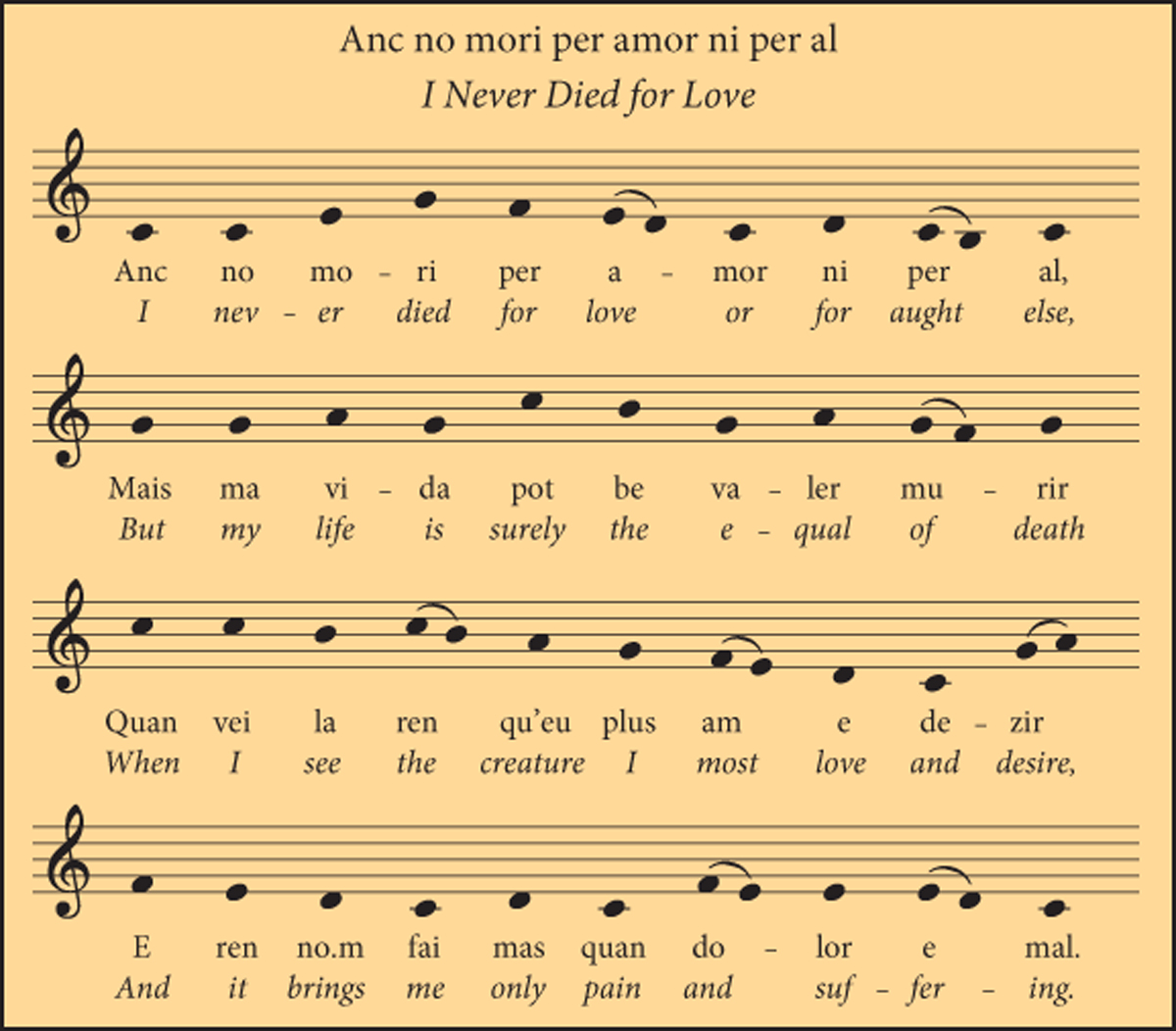

Troubadour poetry was not read; it was sung, typically by a jongleur, a medieval musician. Manuscripts from the thirteenth century show troubadour music written on four- and five-line staves, so scholars can at least determine relative pitches, and modern musicians can sing some troubadour songs with the hope of sounding reasonably like the original. This popular music is the earliest that can be re-created authentically (Figure 11.2).

From southern France, the troubadours’ songs spread to Italy, northern France, England, and Germany. Similar poetry appeared in other vernacular languages: the minnesingers (“love singers”) sang in German; the trouvères sang in the Old French of northern France. One trouvère was the English king Richard the Lion-Hearted. Taken prisoner on his return from the Third Crusade, Richard wrote a poem expressing his longing not for a lady but for the good companions of war, the knightly “youths” he had joined in battle:

They know well, the men of Anjou and Touraine,

. . . that I am arrested, far from them, in another’s hands.

There’s no lordly fighting now on the barren plains,

because I am a prisoner.

Clearly some troubadour poetry was about war rather than love. (See “Document 11.2: Bertran de Born, ‘I love the joyful time of Easter.’”)