Architectural Style: From Romanesque to Gothic

Architectural Style: From Romanesque to Gothic

While Peter the Chanter lectured at Notre Dame, the cathedral itself was going up around him—in Gothic style. This was a new architectural style, associated at first with the Île-de-France and the Capetian kings of France. Elsewhere the reigning style was Romanesque. But in the course of the thirteenth century Gothic style took much of Europe by storm, and by the fourteenth it was the quintessential cathedral style.

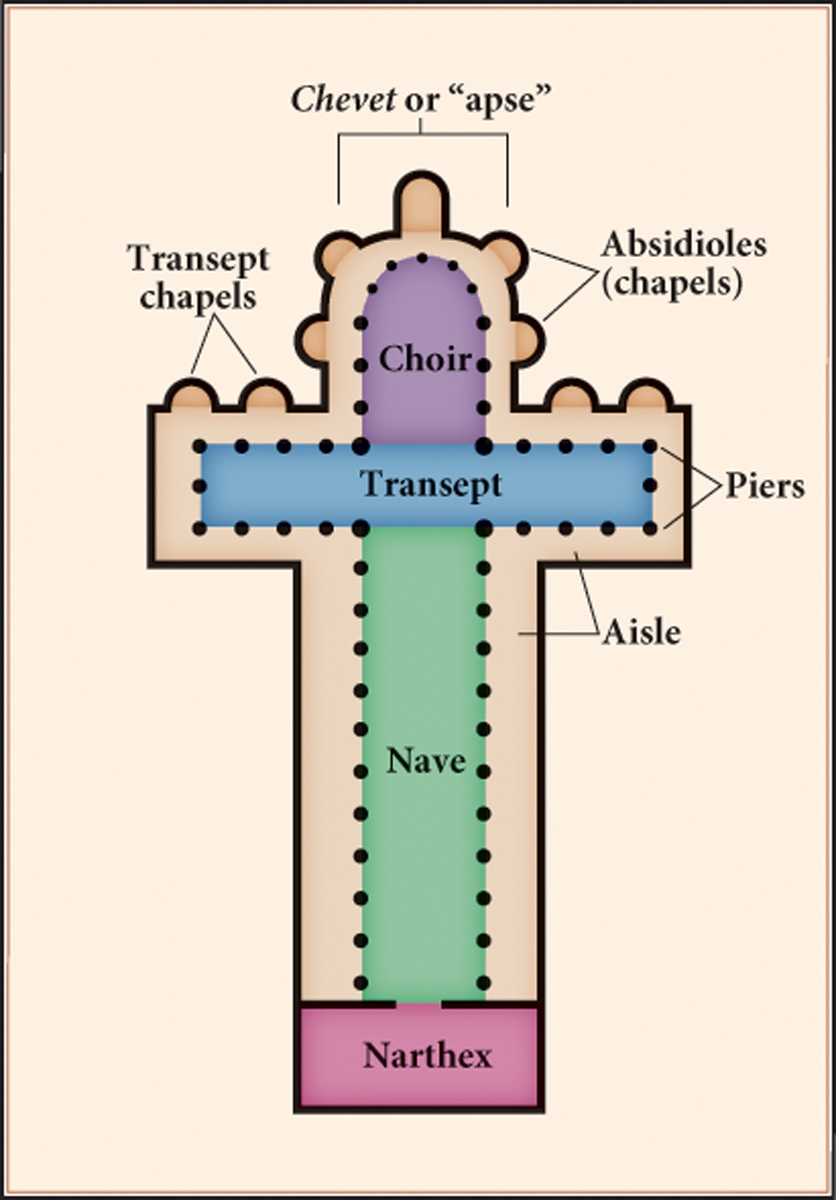

Romanesque is the term art historians use to describe the massive church buildings of eleventh-century monasteries like Cluny. Heavy, serious, and solid, Romanesque churches were decorated with brightly colored wall paintings and sculpture. The various parts of the church—the chapels in the chevet, or apse (the east end), for example—were handled as discrete units, with the forms of cubes, cones, and cylinders (Figure 11.1). Inventive sculptural reliefs, both inside and outside the church, enlivened the geometrical forms. Emotional and sometimes frenzied, Romanesque sculpture depicted themes ranging from the beauty of Eve to the horrors of the Last Judgment. (See the frieze depicting Dives and Lazarus for an example.)

Romanesque churches were above all houses for prayer, which was neither silent nor private. The musical style for prayer was called plainchant, or Gregorian chant. Monks sang plainchant melodies in unison and without instrumental accompaniment. Rhythmically free and lacking a regular beat, plainchant’s melodies ranged from extremely simple to highly ornate and embellished. By the twelfth century, a large repertoire of melodies had grown up, at first composed and transmitted orally and then, starting in the ninth century, using written notation. Echoing within the stone walls and the cavernous choirs, plainchant worked well in a Romanesque church.

Gothic architecture, to the contrary, was a style of the cities, reflecting the self-confidence and wealth of merchants, guildspeople, bishops, and kings.* Usually a cathedral—the bishop’s principal church—rather than a monastic church, the Gothic church was the religious, social, and commercial focal point of a city. The style, popular from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries, was characterized by pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and stained-glass windows. The arches began as architectural motifs but were soon adopted in every art form. Flying buttresses permitted much of the wall to be cut away and the open spaces to be filled with glass. Soaring above the west, north, south, and often east ends of many Gothic churches is a rose window: a large round window shaped like a flower. Gothic churches appealed to the senses the way that Peter the Chanter’s lectures and disputations appealed to human logic and reason: both were designed to lead people to knowledge that touched the divine. The atmosphere of a Gothic church was a foretaste of heaven. (See “Seeing History: Romanesque versus Gothic: The View Down the Nave.”)

The style had its beginnings around 1135, with the project of Abbot Suger, the close associate of King Louis the Fat of France (See “Praising the King of France” in Chapter 10), to remodel portions of the church of Saint-Denis. Suger’s rebuilding was part of the fruitful melding of royal and ecclesiastical interests and ideals in the north of France. At the west end of his church, the place where the faithful entered, Suger decorated the portals with figures of Old Testament kings, queens, and patriarchs, signaling the links between the present king and his illustrious predecessors. At the eastern end, behind the altar, Suger used pointed arches and stained glass to let in light, which Suger believed would transport the worshipper from the “slime of earth” to the “purity of Heaven.” Suger said that the father of lights, God himself, “illuminated” the minds of the beholders through the light that filtered through the stained-glass windows.

REVIEW QUESTION What was new about education and church architecture in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries?

By the mid-thirteenth century, Gothic architecture had spread from France to other European countries. The style varied by region, most dramatically in Italy. At Sant’Andrea in Vercelli, for example, there are only two stories, and light filters in from small windows. Yet with its pointed arches and ribbed vaulting, Sant’Andrea is considered a Gothic church. At its east end is a rose window.