Gothic Art

Gothic Art

Gothic architecture—like philosophy, literature, and music—brought together this world and the next. By the end of the thirteenth century, the Gothic style had spread across most of Europe. Some of its elements began to appear as well in other forms of art, like stained glass. Because pointed arches and flying buttresses allowed the walls of a Gothic church to be pierced with large windows, stained glass became a newly important art form. To make this colored glass, workers added chemicals to sand, heated the mixture until it was liquid, and then blew and flattened it. From these colored glass sheets, artists cut shapes, holding them in place with lead strips. The size of the windows allowed the artists to depict complicated themes ranging from heaven to hell. As the sun shone through the finished windows, they glowed like jewels.

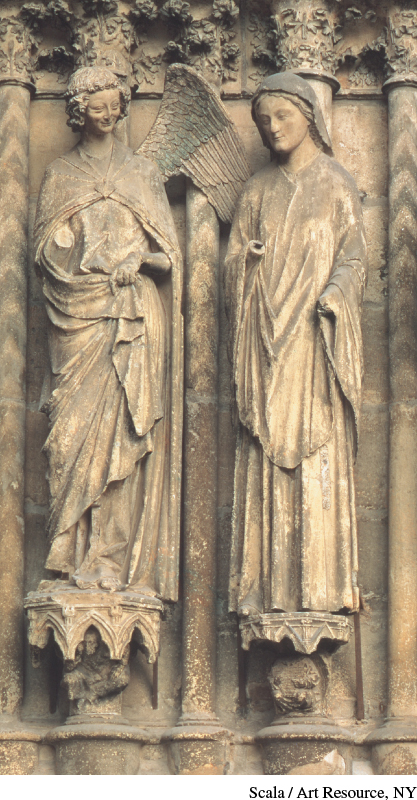

The exteriors of Gothic cathedrals were decorated with figures sculpted in the round. The figures evoked motion—turning, moving, and interacting; at times, they even smiled. Like stained glass, Gothic sculptures evoked complex ideas. For example, the figures on the south portals of the cathedral at Chartres tell the story of the soul’s pilgrimage from the suffering of this world to eternal life: on the left doorway are the martyrs (who died for their beliefs), on the right the confessors (who were tortured), and in the center the Last Judgment (when the good receive eternal life and the bad eternal damnation).

REVIEW QUESTION How did artists, musicians, and scholastics in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries try to link the physical world with the divine?

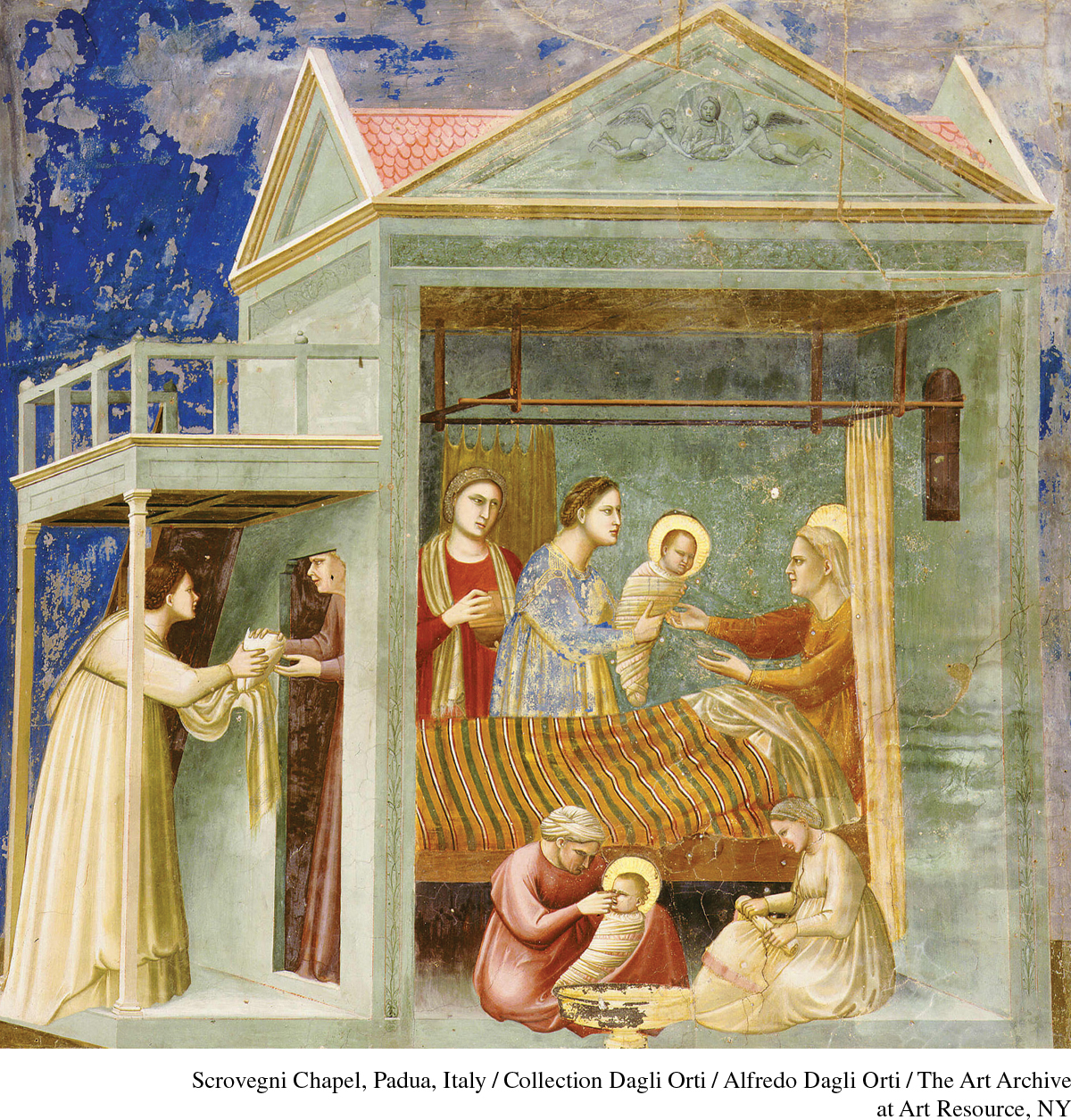

The allure of Gothic was so great that painters began to use elements of its style. Manuscript illuminations feature the pointed shapes of Gothic cathedral windows and vaults as common background themes. (See the Giotto’s Birth of the Virgin for one example.) The colors of Gothic manuscripts echoed the rich hues of stained glass. Gothic sculpture inspired painters like Giotto (1266–1337), an Italian artist. When he filled the walls of a private chapel at Padua with paintings depicting scenes of Christ’s life, Giotto experimented with the illusion of depth, figures in the round, and emotional expression. By fusing naturalistic forms with religious meaning, Giotto found yet another way to fuse the earthly and divine realms. (See “Seeing History: The Agony and the Ecstasy.”)