The Mongol Takeover

The Mongol Takeover

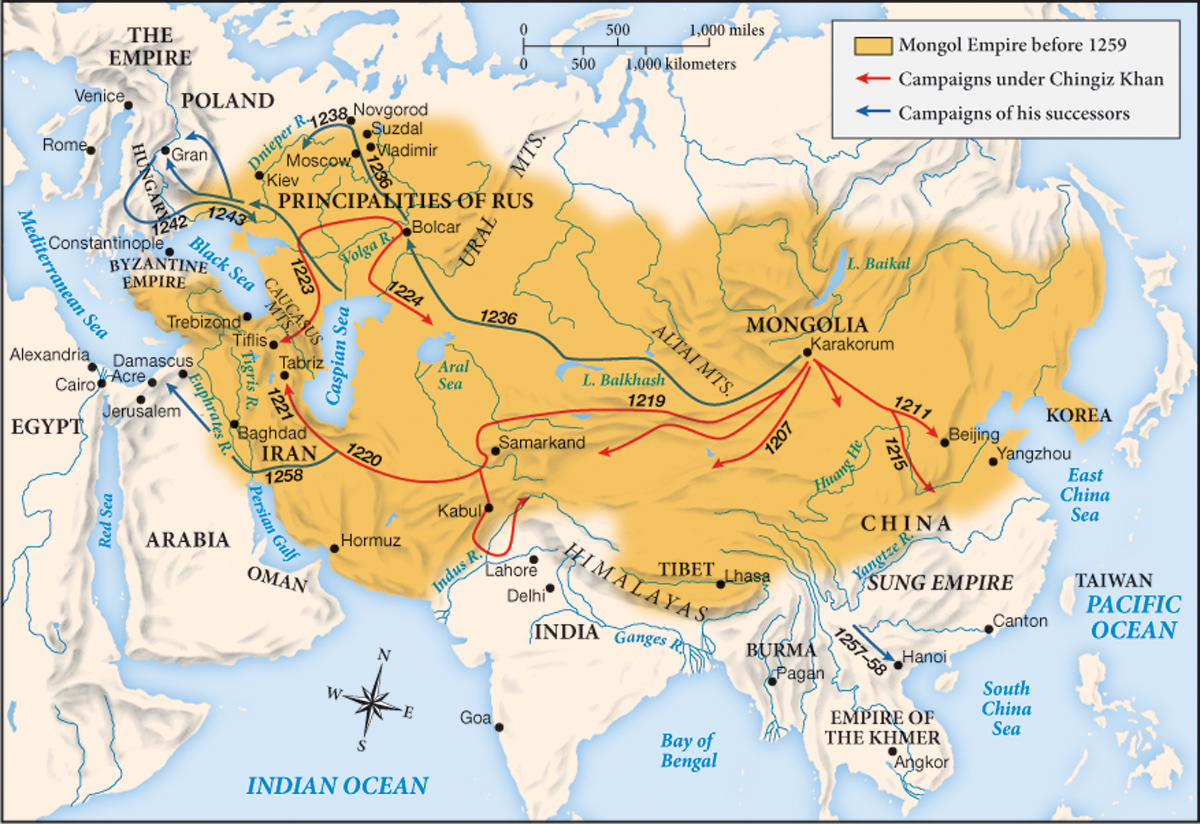

Europeans were not the only warring society in the thirteenth century: to the east, the Mongols (sometimes called Tatars or Tartars) created an aggressive army under the leadership of Chingiz (or Genghis) Khan (c. 1162–1227) and his sons. In part, economic necessity drove them out of Mongolia: changes in climate had reduced the grasslands that sustained their animals and their nomadic way of life. But they were also inspired by Chingiz’s hope of conquering the world. By 1215, the Mongols held Beijing and most of northern China. Some years later, they moved through central Asia and skirted the Caspian Sea (Map 12.2).

In the 1230s, the Mongols began concerted attacks against Rus, Poland, and Hungary, where native princes were weak. Fighting mainly on horseback with heavy lances and powerful bows and arrows whose shots traveled far and penetrated deeply, the Mongols initially pushed through Hungary. Only the death of the second Great Khan, Chingiz’s son Ogodei (1186–1241), and disputes over his succession prevented a concentrated assault on Germany. In the 1250s, the Mongols took Iran and Iraq. (See “Contrasting Views: The Mongols: Instruments of God or Cruel Invaders?”)

Soon retreating from Hungary, the Mongols established themselves in Rus, where in 1240 they had captured Kiev. This remained the center of their power, but they dominated all of Russia for about two hundred years. The Mongol Empire in Rus, later called the Golden Horde (golden probably from the color of their leader’s tent; horde from a Turkish word meaning “camp”), adopted much of the local government apparatus and left many of the old institutions in place. The Mongols allowed Rus princes to continue ruling as long as those princes paid homage and tribute to the khan, and they tolerated the Rus church, exempting it from taxes. The Mongols’ chief undertaking was a series of population censuses on the basis of which they recalculated taxes and recruited troops.

The Mongol invasion changed the political configuration of Europe and Asia. Because the Mongols were willing to deal with Westerners, one effect of their conquests was to open China to European travelers for the first time. Missionaries, diplomats, and merchants went to China over land routes and via the Persian Gulf. Some of these voyagers hoped to enlist the aid of the Mongols against the Muslims, others expected to make new converts to Christianity, and still others dreamed of lucrative trade routes.

The most famous of these travelers was Marco Polo (1254–1324), who remained in China for nearly two years. Others stayed even longer. In fact, evidence suggests that an entire community of Venetian traders lived in the city of Yangzhou in the mid-fourteenth century. Such merchants paved the way for missionaries. Friars, who were preachers to the cities of Europe, became missionaries to new continents as well.

The long-term effect of the Mongols on the West was to open up new land routes to the East that helped bind together the two halves of the known world. Travel stories such as Marco Polo’s account of his journeys stimulated others to seek out the fabulous riches—textiles, ginger, ceramics, copper—of China and other regions of the East. In a sense, the Mongols initiated the search for exotic goods and missionary opportunities that culminated in the European “discovery” of a new world, the Americas.