Protestant Challenges to the Social Order

Protestant Challenges to the Social Order

When Luther described the freedom of the Christian, he meant an entirely spiritual freedom. But others interpreted his call for freedom in social and political terms. In the spring of 1525, peasants in southern and central Germany rose in a rebellion known as the Peasants’ War and attacked nobles’ castles, convents, and monasteries (Map 14.2). Urban workers joined them, and together they looted church properties in the towns. In Thuringia (central/eastern Germany), the rebels followed an ex-priest, Thomas Müntzer (1468?–1525), who promised to chastise the wicked and thus clear the way for the Last Judgment.

The Peasants’ War split the reform movement. Princes and city officials, ultimately supported by Luther, turned against the rebels. Catholic and Protestant princes joined forces to crush Müntzer and his supporters. All over the empire, princes trounced peasant armies and hunted down their leaders. By the end of the year, more than 100,000 rebels had been killed. Initially, Luther had tried to mediate the conflict, but he believed that God ordained rulers, who must therefore be obeyed even if they were tyrants. Luther considered Müntzer’s mixing of religion and politics the greatest danger to the Reformation, nothing less than “the devil’s work.” Fundamentally conservative in its political philosophy, the Lutheran church henceforth depended on established political authority for its protection.

Some followers of Zwingli also wanted to pursue their own path to reform. They believed that true faith came only to those with reason and free will. How could a baby knowingly choose Christ? Only adults could believe and accept baptism; hence, the Anabaptists (“rebaptizers”) rejected the validity of infant baptism and called for adult rebaptism. Many were pacifists who also refused to acknowledge the authority of law courts. The Anabaptist movement drew its leadership primarily from the artisan class and its members from the middle and lower classes—men and women attracted by a simple but radical message of peace and salvation.

Zwingli immediately attacked the Anabaptists for their refusal to bear arms and swear oaths of allegiance, sensing accurately that they were repudiating his theocratic (church-directed) order. When persuasion failed to convince the Anabaptists, Zwingli urged Zurich magistrates to impose the death sentence. Thus, the Evangelical reformers themselves created the Reformation’s first martyrs of conscience.

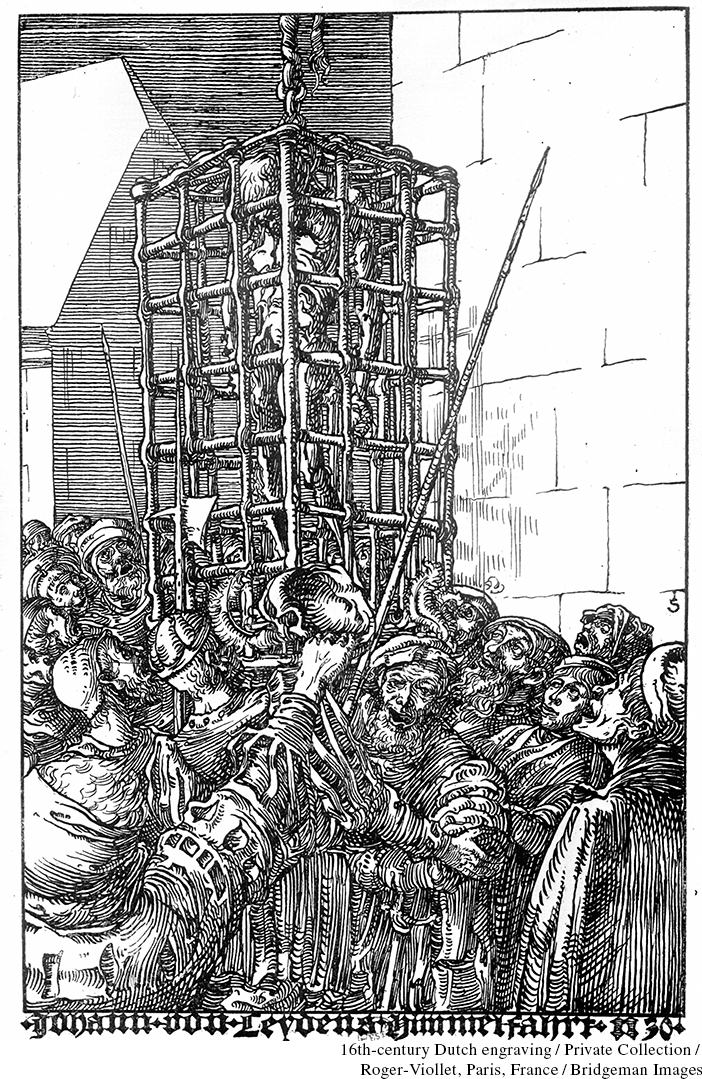

Despite the Holy Roman Emperor’s condemnation of the movement in 1529, Anabaptism spread rapidly from Zurich to many cities in southern Germany. In 1534, one Anabaptist group, believing the end of the world was imminent, seized control of the city of Münster. Proclaiming themselves a community of saints, the Münster Anabaptists abolished private property in imitation of the early Christians and dissolved traditional marriages, allowing men, like Old Testament patriarchs, to have multiple wives, to the consternation of many women. Besieged by a combined Protestant and Catholic army, the city fell in June 1535. The Anabaptist leaders died in battle or were executed, their bodies hung in cages affixed to the church tower. Their punishment was intended as a warning to all who might want to take the Reformation away from the Protestant authorities and hand it to the people. The Anabaptist movement in northwestern Europe nonetheless survived under the determined pacifist leadership of the Dutch reformer Menno Simons (1469–1561), whose followers were eventually named Mennonites.