Magic and Witchcraft

Magic and Witchcraft

Although artists, political thinkers, and scientific experimenters increasingly pursued secular goals, most remained as devout in their religious beliefs as ordinary people. Many scholars, including Newton, studied alchemy alongside their scientific pursuits. Alchemists aimed to discover techniques for turning lead and copper into gold. The astronomer Tycho Brahe defended his studies of alchemy and astrology as part of “natural magic,” as opposed to demonic “black magic.”

Learned and ordinary people alike also firmly believed in witchcraft, that is, the exercise of magical powers gained by a pact with the devil. The same Jean Bodin who argued against religious fanaticism insisted on death for witches—and for those magistrates who would not prosecute them. Trials of witches peaked in Europe between 1560 and 1640, the very time of the celebrated breakthroughs of the new science. Montaigne was one of the few to speak out against executing accused witches: “It is taking one’s conjectures rather seriously to roast someone alive for them,” he wrote in 1580.

Witches had long been blamed for destroying crops and causing personal catastrophes ranging from miscarriage to madness, but never before had they been officially persecuted in such numbers. Denunciation and persecution of witches coincided with the spread of reform, both Protestant and Catholic. Witch trials concentrated especially in the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, the boiling cauldron of the Thirty Years’ War.

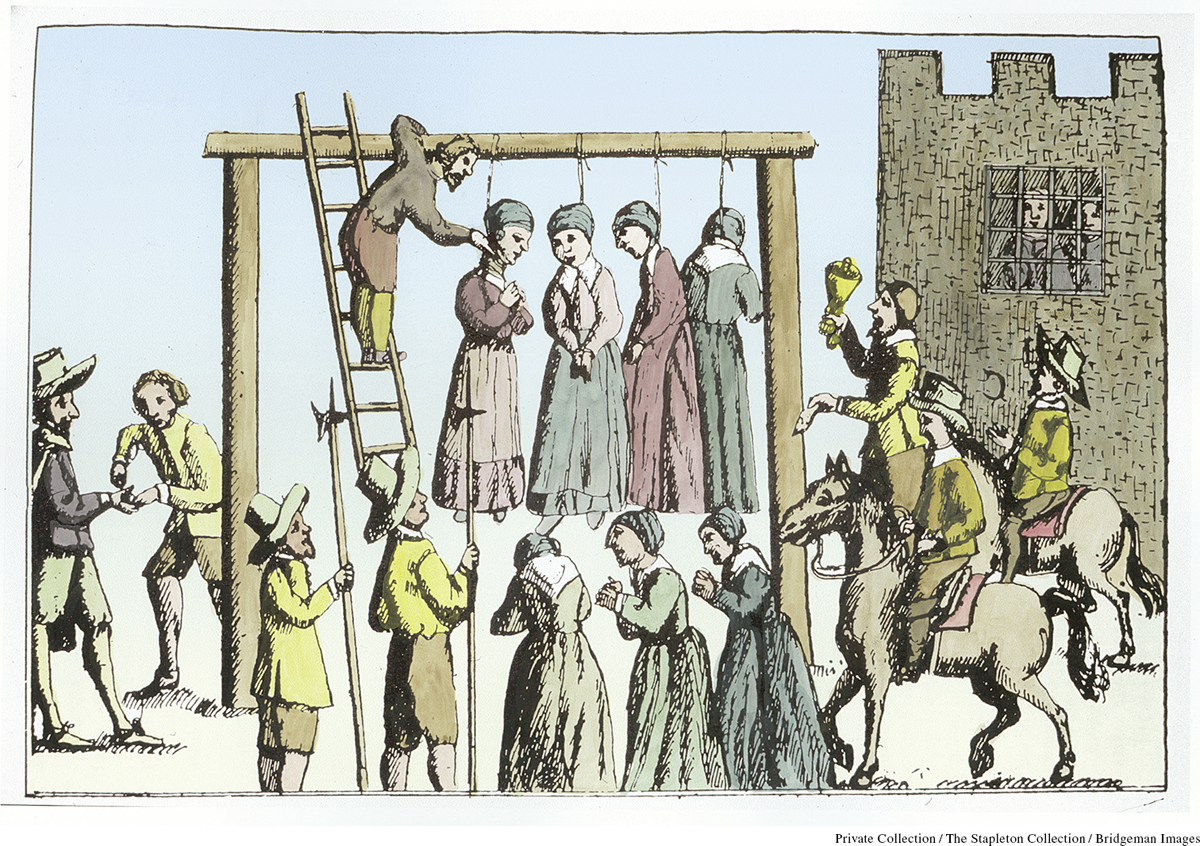

The victims of the persecution were overwhelmingly female: women accounted for 80 percent of the accused witches in about 100,000 trials in Europe and North America during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. About one-third were sentenced to death. Before 1400, when witchcraft trials were rare, nearly half of those accused had been men. Why did attention now shift to women? Some official descriptions of witchcraft oozed lurid details of sexual orgies, in which women acted as the devil’s sexual slaves. Social factors help explain the prominence of women among the accused. Accusers were almost always better off than those they accused. The poorest and most socially marginal people in most communities were elderly spinsters and widows. Because they were thought likely to hanker after revenge on those more fortunate, they were singled out as witches.

REVIEW QUESTION How could belief in witchcraft and the rising prestige of the scientific method coexist?

The tide turned against witchcraft trials when physicians, lawyers, judges, and even clergy came to suspect that accusations were based on superstition and fear. In 1682, a French royal decree treated witchcraft as fraud and imposture, meaning that the law did not recognize anyone as a witch. In 1693, the jurors who had convicted twenty people of witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts, recanted, claiming: “We justly fear that we were sadly deluded and mistaken.” The Salem jurors had not stopped believing in witches; they had simply lost confidence in their ability to identify them. When physicians and judges had believed in witches and carried out official persecutions, with torture, those accused of witchcraft had gone to their deaths in record numbers. But when the same groups distanced themselves from popular beliefs, the trials and the executions stopped.