Russia: Setting the Foundations of Bureaucratic Absolutism

Russia: Setting the Foundations of Bureaucratic Absolutism

Seventeenth-century Russia seemed a world apart from the Europe of Leopold I and Louis XIV. Straddling Europe and Asia, the Russian lands stretched across Siberia to the Pacific Ocean. Western visitors either sneered or shuddered at the “barbarism” of Russian life, and Russians reciprocated by nursing deep suspicions of everything foreign. But under the surface, Russia was evolving as an absolutist state; the tsars wanted to claim unlimited autocratic power, but like their European counterparts they had to surmount internal disorder and come to an accommodation with noble landlords.

In 1649, the Russian tsar Alexei (r. 1645–1676) convened the Assembly of the Land (consisting of noble delegates from the provinces) to consult on a sweeping law code to organize Russian society in a strict social hierarchy. The code of 1649—which held for nearly two centuries—assigned all subjects to a hereditary class according to their current occupation or state needs. Slaves and free peasants were merged into a serf class. As serfs, they could not change occupations or move; they were tightly tied to the soil and to their noble masters. To prevent tax evasion, the code also forbade townspeople to move from the community where they resided. Nobles owed absolute obedience to the tsar and were required to serve in the army, but in return no other group could own estates worked by serfs. Serfs became the chattel of their lord, who could sell them like horses or land. Their lives differed little from those of the slaves on the plantations in the Americas.

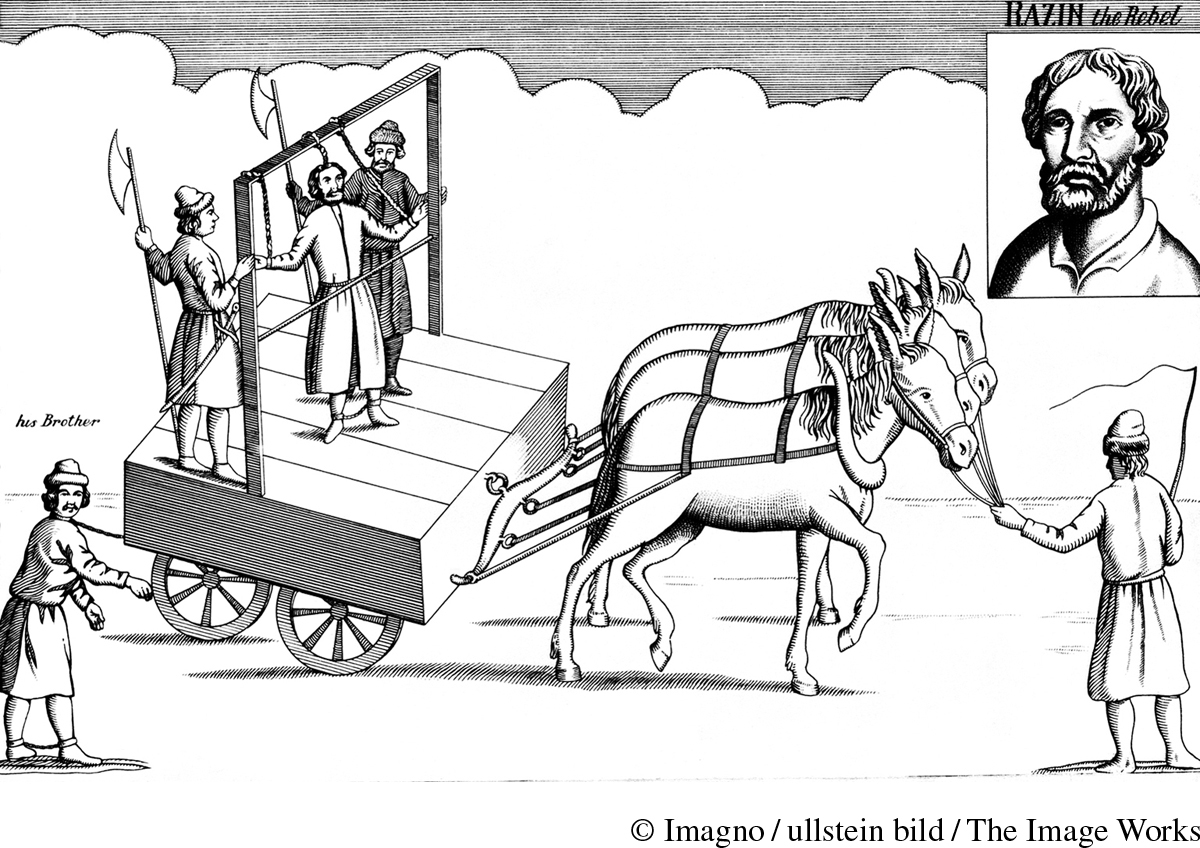

Some peasants resisted enserfment. In 1667, Stenka Razin (1630–1671), the head of a powerful band of pirates and outlaws in southern Russia, led a rebellion that promised liberation from the great noble landowners. Captured four years later by the tsar’s army, Razin was taken to Moscow, where he was dismembered in front of the public and his body thrown to the dogs. Thousands of his followers also suffered grisly deaths, but Razin’s memory lived on in folk songs and legends.

Like his Western rivals, Tsar Alexei wanted a bigger army, exclusive control over state policy, and a greater say in religious matters. The size of the army increased dramatically from 35,000 in the 1630s to 220,000 by the end of the century. The Assembly of the Land, once an important source of consultation for the nobles, never met again after 1653. Alexei also imposed firm control over the Russian Orthodox church. The state-dominated church took action against a religious group called the Old Believers, who rejected church efforts to bring Russian worship in line with Byzantine tradition. Whole communities of Old Believers starved or burned themselves to death rather than submit to the crown.

REVIEW QUESTION Why did absolutism flourish everywhere in eastern Europe except Poland-Lithuania?

Nevertheless, modernizing trends prevailed. Tsar Alexei set up the first Western-style theater in the Kremlin, and his daughter Sophia translated French plays. The most adventurous nobles began to wear German-style clothing. Some even argued that service, not just birth, should determine rank. Russia’s long struggle over Western influences had begun.