Travel Literature and the Challenge to Custom and Tradition

Travel Literature and the Challenge to Custom and Tradition

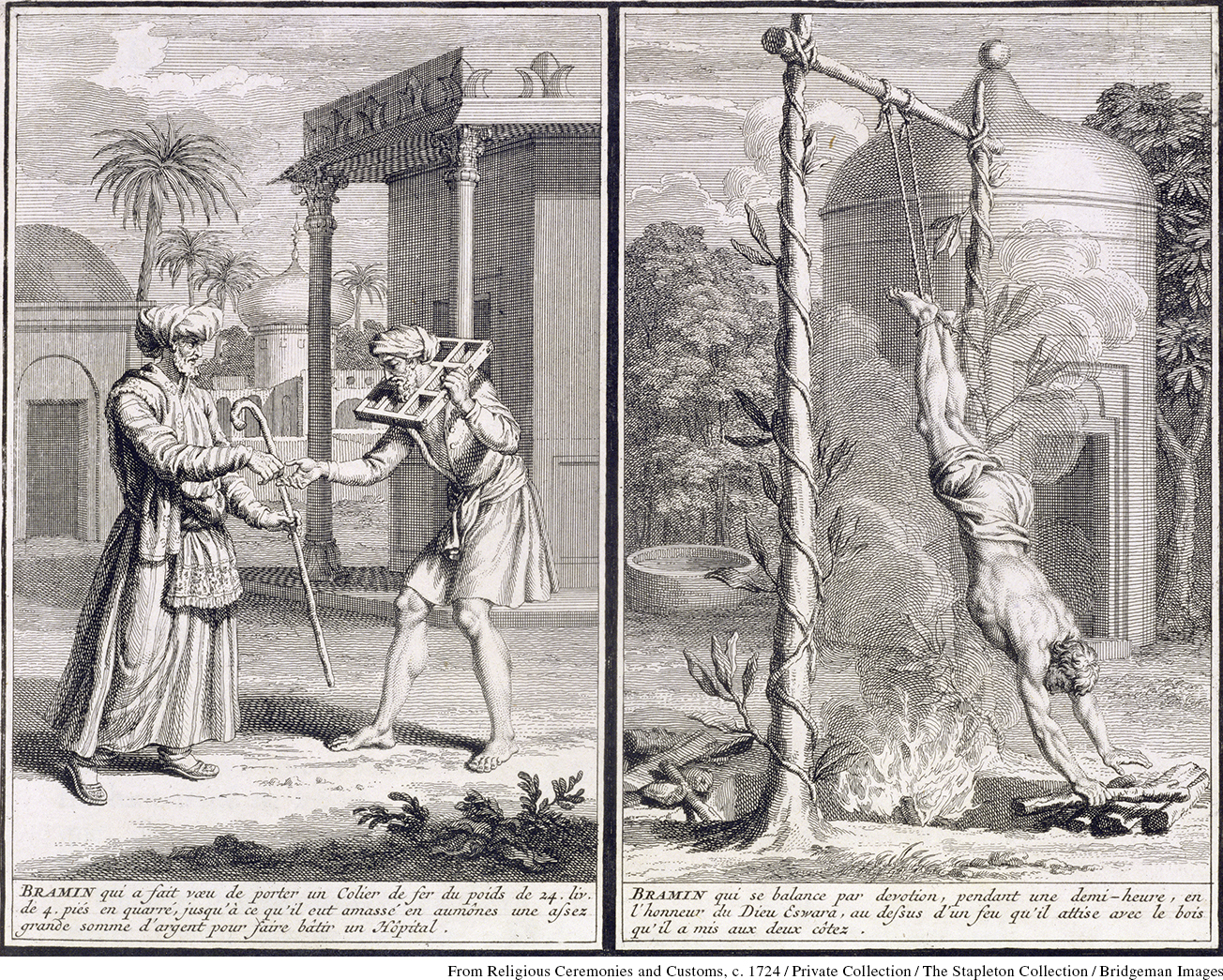

Just as scientific method could be used to question religious and even state authority, a more general skepticism also emerged from the expanding knowledge about the world outside of Europe. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the number of travel accounts dramatically increased as travel writers used the contrast between their home societies and other cultures to criticize the customs of European society.

Travelers to the Americas found “noble savages” (native peoples) who appeared to live in conditions of great freedom and equality; they were “naturally good” and “happy” without taxes, lawsuits, or much organized government. In China, in contrast, travelers found a people who enjoyed prosperity and an ancient civilization. Christian missionaries made little headway in China, and visitors had to admit that China’s religious systems had flourished for four or five thousand years with no input from Europe or from Christianity. The basic lesson of travel literature in the 1700s, then, was that customs varied: justice, freedom, property, good government, religion, and morality all were relative to the place. One critic complained that travel encouraged the destruction of religion: “Some complete their demoralization by extensive travel, and lose whatever shreds of religion remained to them. Every day they see a new religion, new customs, new rites.”

Travel literature turned explicitly political in Montesquieu’s Persian Letters (1721). Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron of Montesquieu (1689–1755), the son of an eminent judicial family, was a high-ranking judge in a French court. He published Persian Letters anonymously in the Dutch Republic, and the book went into ten printings in just one year—a best seller for the times. Montesquieu tells the fictional story of two Persians, Rica and Usbek, who visit France in the last years of Louis XIV’s reign and write home with their impressions. By imagining an outsider’s perspective, Montesquieu could satirize French customs and politics without taking them on directly. Montesquieu chose Persians for his travelers because they came from what was widely considered the most despotic of all governments, in which rulers had life-and-death powers over their subjects. In the book, the Persians constantly compare France to Persia, suggesting that the French monarchy might verge on despotism. (See “Document 17.2: Montesquieu, Persian Letters: Letter 37.”)

Montesquieu’s anonymity did not last long, and in the late 1720s, he sold his judgeship and traveled extensively in Europe, staying eighteen months in Britain. In 1748, he published a widely influential work on comparative government, The Spirit of Laws. Like the politique Jean Bodin before him (see “The Natural Law of Politics” in Chapter 15), Montesquieu examined the various types of government, but unlike Bodin he did not favor absolute power in a monarchy. His time in Britain made him much more favorable to constitutional forms of government. The Catholic church soon listed both Persian Letters and The Spirit of Laws on its Index (its list of forbidden books).