World Trade and Settlement

World Trade and Settlement

The Atlantic system helped extend European trade relations across the globe. The textiles that Atlantic shippers exchanged for slaves on the west coast of Africa, for example, were manufactured in India and exported by the British and French East India Companies. As much as one-quarter of the British exports to Africa in the eighteenth century were actually re-exports from India. To expand their trade in the rest of the world, Europeans seized territories and tried to establish permanent settlements. The eighteenth-century extension of European power prepared the way for Western global domination in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In contrast to the sparsely inhabited European trading outposts in Asia and Africa, the colonies in the Americas bulged with settlers. The British North American colonies contained about 1.5 million nonnative (that is, white settler and black slave) residents by 1750. While the Spanish competed with the Portuguese for control of South America, the French competed with the British for control of North America.

Local economies shaped colonial social relations; men in French trapper communities in Canada, for example, had little in common with the men and women of the plantation societies in Barbados or Brazil. Racial attitudes also differed from place to place. Unlike the French and English, the Spanish and Portuguese tolerated intermarriage with the native populations in both America and Asia. By 1800, mestizos, people born to a Spanish father and an Indian mother, accounted for more than a quarter of the population in the Spanish colonies. Where intermarriage between colonizers and natives was common, conversion to Christianity proved most successful. However, greater racial diversity seems not to have improved the treatment of slaves. (See “Document 17.1: European Views of Indian Religious Practices.”)

In the early years of American colonization, many more men than women emigrated from Europe. Although the sex imbalance began to decline at the end of the seventeenth century, it remained substantial; two and a half times more men than women were among the immigrants leaving Liverpool, England, between 1697 and 1707, for example. Women who emigrated as indentured servants ran great risks: many died of disease during the voyage, and at least one in five gave birth to an illegitimate child.

However, the uncertainties of life in the American colonies provided new opportunities for European women and men willing to live outside the law. In the 1500s and 1600s, the English and Dutch governments had routinely authorized pirates to prey on the ships of their rivals, the Spanish and Portuguese. Then, in the late 1600s, English, French, and Dutch bands made up of deserters and crews from wrecked vessels began to form their own associations of pirates, especially in the Caribbean. Called buccaneers from their custom of curing strips of beef, called boucan by the native Caribs of the islands, the pirates governed themselves and preyed on everyone’s shipments without regard to national origin. After 1700, the colonial governments tried to stamp out piracy.

In comparison to those in the Americas, white settlements in Africa and Asia remained small. A handful of Portuguese trading posts in Angola and a few Dutch farms on the Cape of Good Hope provided the only toeholds in Africa for future expansion. In China, the emperors had welcomed Catholic missionaries at court in the seventeenth century, but the priests’ credibility diminished as they squabbled among themselves and associated with European merchants, whom the Chinese considered pirates. In 1720, only one thousand Europeans resided in Guangzhou (Canton), the sole place where foreigners could legally trade for spices, tea, and silk (see Map 17.1).

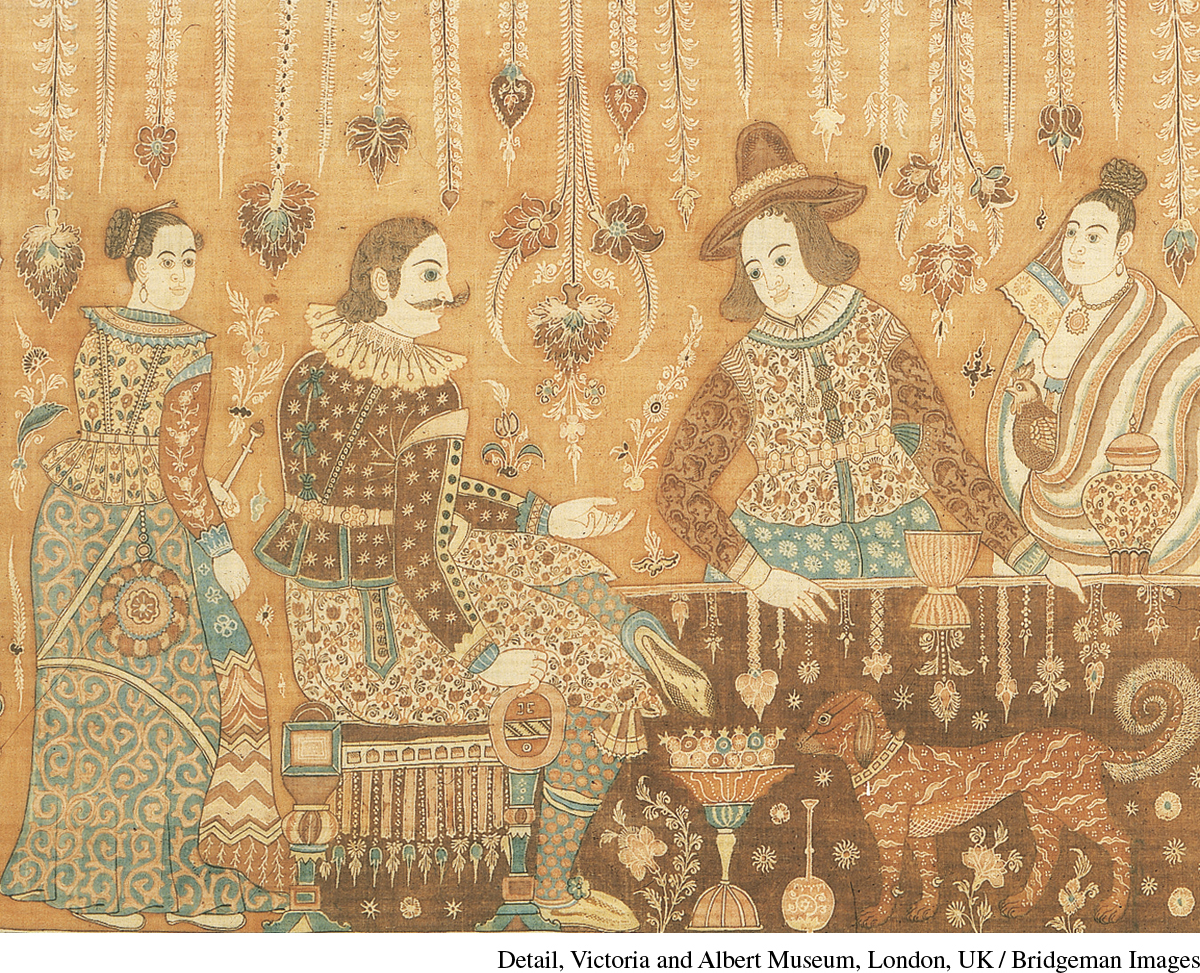

Europeans exercised more influence in Java (in what was then called the East Indies) and in India. Many Dutch settled in Java to oversee coffee production and Asian trade. Dutch, English, French, Portuguese, and Danish companies competed in India for spices, cotton, and silk; by the 1740s, the English and French had become the leading rivals in India, just as they were in North America. Both countries extended their power as India’s Muslim rulers lost control to local Hindu princes, rebellious Sikhs, invading Persians, and their own provincial governors. A few thousand Europeans lived in India, though many thousand more soldiers were stationed there to protect them. The staple of trade with India in the early 1700s was calico—lightweight, brightly colored cotton cloth that caught on as a fashion in Europe. English and French slave traders sold calico to the Africans in exchange for slaves.