War and Diplomacy

War and Diplomacy

Europeans no longer fought devastating wars over religion that killed hundreds of thousands of civilians; instead, professional armies and navies battled for control of overseas empires and for dominance on the European continent. Rulers continued to expand their armies: the Prussian army, for example, nearly tripled in size between 1740 and 1789. Widespread use of flintlock muskets required deployment in long lines, usually three men deep, with each line in turn loading and firing on command. Military strategy became cautious and calculating, but this did not prevent the outbreak of hostilities. Between 1750 and 1775, the instability of the European balance of power resulted in a diplomatic reversal of alliances, a major international conflict, and the partition of Poland-Lithuania among Russia, Austria, and Prussia.

In 1756, a set of events that historians call the Diplomatic Revolution reshaped relations among the great powers. Prussia and Great Britain signed a defensive alliance, prompting Austria to overlook two centuries of hostility and ally with France. Russia and Sweden soon joined the Franco-Austrian alliance. When Frederick the Great invaded Austria’s ally Saxony with his large, well-disciplined army, the long-simmering hostilities between Great Britain and France over colonial boundaries flared into a general war that became known as the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763).

Fighting soon raged around the world (Map 18.1). The French and British battled on land and sea in North America (where the conflict was called the French and Indian War), the West Indies, and India. The two coalitions also fought each other in central Europe. At first, in 1757, Frederick the Great surprised Europe with a spectacular victory at Rossbach in Saxony over a much larger Franco-Austrian army. But in time, Russian and Austrian armies encircled his troops. A fluke of history saved him. Empress Elizabeth of Russia (r. 1741–1762) died and was succeeded by the mentally unstable Peter III, a fanatical admirer of Frederick and all things Prussian. Peter withdrew Russia from the war. (This was practically his only accomplishment as tsar. He was soon mysteriously murdered, probably at the instigation of his wife, Catherine the Great.) A separate peace treaty allowed Frederick to keep all his territory, including Silesia, that had been conquered in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748).

The Anglo-French overseas conflicts ended more decisively than the continental land wars. British naval superiority, fully achieved only in the 1750s, enabled Great Britain to rout the French in North America, India, and the West Indies. In the Treaty of Paris of 1763, France ceded Canada to Great Britain and agreed to remove its armies from India, in exchange for keeping its rich West Indian islands. Eagerness to avenge this defeat would motivate France to support the British North American colonists in their War of Independence just fifteen years later.

Although Prussia suffered great losses in the Seven Years’ War—some 160,000 Prussian soldiers died either in action or of disease—its army helped vault Prussia to the rank of leading powers. By 1740, the Prussians had the third or fourth largest army in Europe even though Prussia was tenth in population and thirteenth in land area. Under Frederick II, Prussia’s military expenditures rose to two-thirds of the state’s revenue. Virtually every nobleman served in the army, paying for his own support as officer and buying a position as company commander. Once retired, the officers returned to their estates and served as local officials. This militarization of Prussian society had a profoundly conservative effect: it kept the peasants enserfed to their lords and blocked the middle classes from access to estates or high government positions.

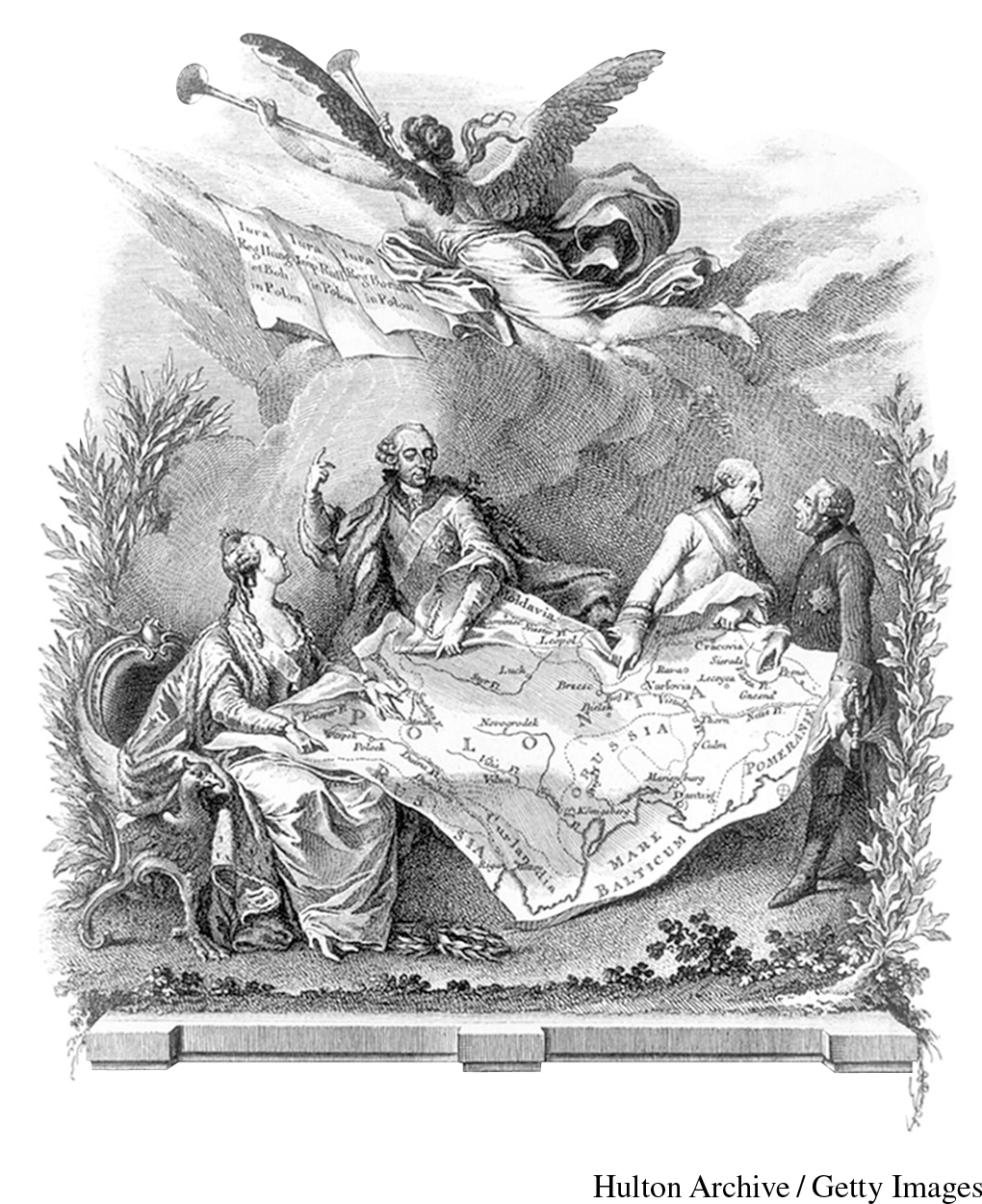

Prussia’s power grew so dramatically that in 1772 Frederick the Great proposed that large chunks of Poland-Lithuania be divided among Austria, Prussia, and Russia. Although the Austrian empress Maria Theresa protested that the partition would spread “a stain over my whole reign,” she agreed to the first partition of Poland, splitting one-third of Poland-Lithuania’s territory and half of its people among the three powers. Russia took over most of Lithuania, effectively ending the large but weak Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth.