Revolution in North America

Revolution in North America

Oppositional forms of public opinion came to a head in Great Britain’s North American colonies, where the result was American independence and the establishment of a republican constitution that stood in stark contrast to most European regimes. Many Europeans saw the American War of Independence, or the American Revolution, as a triumph for Enlightenment ideas. As one German writer exclaimed in 1777, American victory would give “greater scope to the Enlightenment, new keenness to the thinking of peoples and new life to the spirit of liberty.”

The American revolutionary leaders had participated in the Enlightenment and shared political ideas with the opposition Whigs in Britain. In the 1760s and 1770s, American opposition leaders became convinced that the British government was growing increasingly corrupt and despotic. The colonies had no representatives in Parliament, and colonists claimed that “no taxation without representation” should be allowed. Indeed, they denied that Parliament had any jurisdiction over the colonies, insisting that the king govern them through colonial legislatures and recognize their traditional British liberties. The failure of the “Wilkes and Liberty” campaign to produce concrete results convinced many Americans that Parliament was hopelessly tainted.

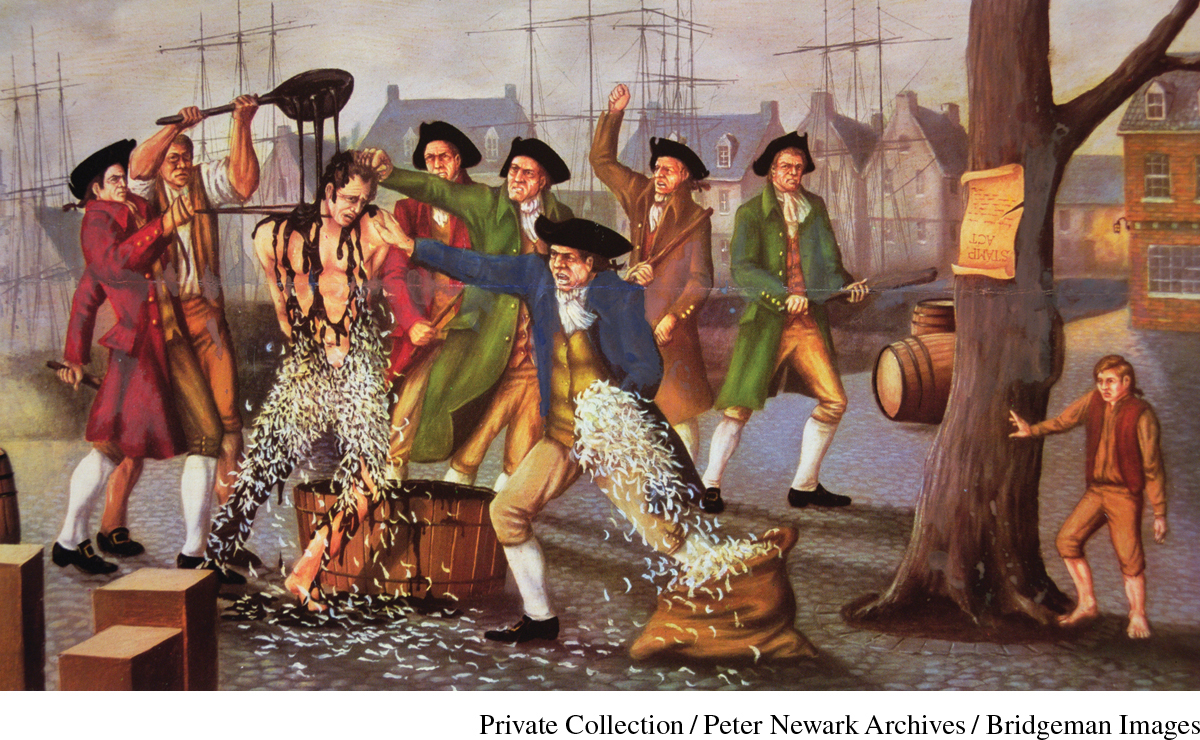

Parliament’s encroachment on the autonomy of the colonies transformed colonial attitudes. With the British clamoring for lower taxes at the end of the Seven Years’ War and the colonists paying only a fraction of the tax rate paid by the Britons at home, Parliament passed new taxes on the colonies, including the Stamp Act in 1765, which required a special tax stamp on all legal documents and publications. After violent rioting in the colonies, the British repealed the tax, but in 1773 the new Tea Act revived colonial resistance, which culminated in the so-called Boston Tea Party of 1773. Colonists dressed as Indians boarded British ships and dumped the imported tea (by this time an enormously popular beverage) into Boston’s harbor.

Political opposition in the American colonies turned belligerent when Britain threatened to use force to maintain control. After actual fighting had begun, in 1776, the Second Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence. An eloquent statement of the American cause drafted by the Virginia planter and lawyer Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration of Independence was couched in the language of universal human rights, which enlightened Europeans could be expected to understand. In 1778, France boosted the American cause by entering on the colonists’ side. Spain declared war on Britain in 1779; in 1780, Great Britain declared war on the Dutch Republic in retaliation for Dutch support of the rebels. The worldwide conflict that resulted was more than Britain could handle. The American colonies achieved their independence in the peace treaty of 1783. (See “Document 18.2: Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence.”)

The newly independent states still faced the challenge of republican self-government. The Articles of Confederation, drawn up in 1777 as a provisional constitution, proved weak because they gave the central government few powers. In 1787, a constitutional convention met in Philadelphia to draft a new constitution, which was ratified the following year. It established a two-house legislature, an indirectly elected president, and an independent judiciary. The U.S. Constitution’s preamble insisted explicitly, for the first time in history, that government derived its power solely from the people and did not depend on divine right or on the tradition of royalty or aristocracy. The new educated elite of the eighteenth century had now created government based on a “social contract” among male, property-owning, white citizens. It was by no means a complete democracy (women and slaves were excluded from political participation), but the new government represented a radical departure from European models. Appended to the Constitution in 1791, the Bill of Rights outlined the essential rights (such as freedom of speech) that the government could never overturn. Although slavery continued in the American republic, the new emphasis on rights helped fuel the movement for its abolition in both Britain and the United States.

REVIEW QUESTION Why did public opinion become a new factor in politics in the second half of the eighteenth century?

Interest in the new republic was greatest in France. The U.S. Constitution and various state constitutions were published in French with commentary by leading thinkers. Even more important in the long run were the effects of the American war. Dutch losses to Great Britain aroused a widespread movement for political reform in the Dutch Republic, and debts incurred by France in supporting the American colonies would soon force the French monarchy to the edge of bankruptcy and then to revolution. Ultimately, the entire European system of royal rule would be challenged.