Men and Women of the Republic of Letters

Men and Women of the Republic of Letters

Although philosophe is a French word, the Enlightenment was distinctly cosmopolitan; philosophes could be found from Philadelphia to St. Petersburg. The philosophes considered themselves part of a grand “republic of letters” that transcended national political boundaries. They were not republicans in the usual sense, that is, people who supported representative government and opposed monarchy. What united them were the ideals of reason, reform, and freedom. In 1784, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant summed up the program of the Enlightenment in two Latin words: sapere aude (“dare to know”)—have the courage to think for yourself.

The philosophes used reason to attack superstition, bigotry, and religious fanaticism, which they considered the chief obstacles to free thought and social reform. Voltaire took religious fanaticism as his chief target: “Once fanaticism has corrupted a mind, the malady is almost incurable. . . . The only remedy for this epidemic malady is the philosophical spirit.” Enlightenment writers did not necessarily oppose organized religion, but they strenuously objected to religious intolerance. They believed that the systematic application of reason could do what religious belief could not: improve the human condition by pointing to needed reforms. Reason meant critical, informed, scientific thinking about social issues and problems.

Many Enlightenment writers collaborated on the multivolume Encyclopedia (published 1751–1772), which aimed to gather together knowledge about science, religion, industry, and society. The ancestor of all modern encyclopedias from the Encyclopædia Britannica to Wikipedia online, the Enlightenment version differed by using knowledge to criticize defects in society. The chief editor of the Encyclopedia, Denis Diderot (1713–1784), explained the goal: “All things must be examined, debated, investigated without exception and without regard for anyone’s feelings.” (See “Document 18.1: Denis Diderot, Encyclopedia.”)

The philosophes believed that the spread of knowledge would encourage reform in every aspect of life, from the grain trade to the penal system. Chief among their desired reforms was intellectual freedom—the freedom to use one’s own reason to conduct studies and to publish the results. The philosophes wanted freedom of the press and freedom of religion, which they considered “natural rights” guaranteed by “natural law.” In their view, progress depended on these freedoms.

Most philosophes, like Voltaire, came from the upper classes, yet the Swiss philosophe Jean-Jacques Rousseau had been born to a modest watchmaker in Geneva, and Diderot was the son of a cutlery maker. Rarely were women philosophes; one, however, was the French noblewoman Émilie du Châtelet (1706–1749), who wrote extensively about the mathematics and physics of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Isaac Newton. (Châtelet’s lover Voltaire learned much of his science from her.)

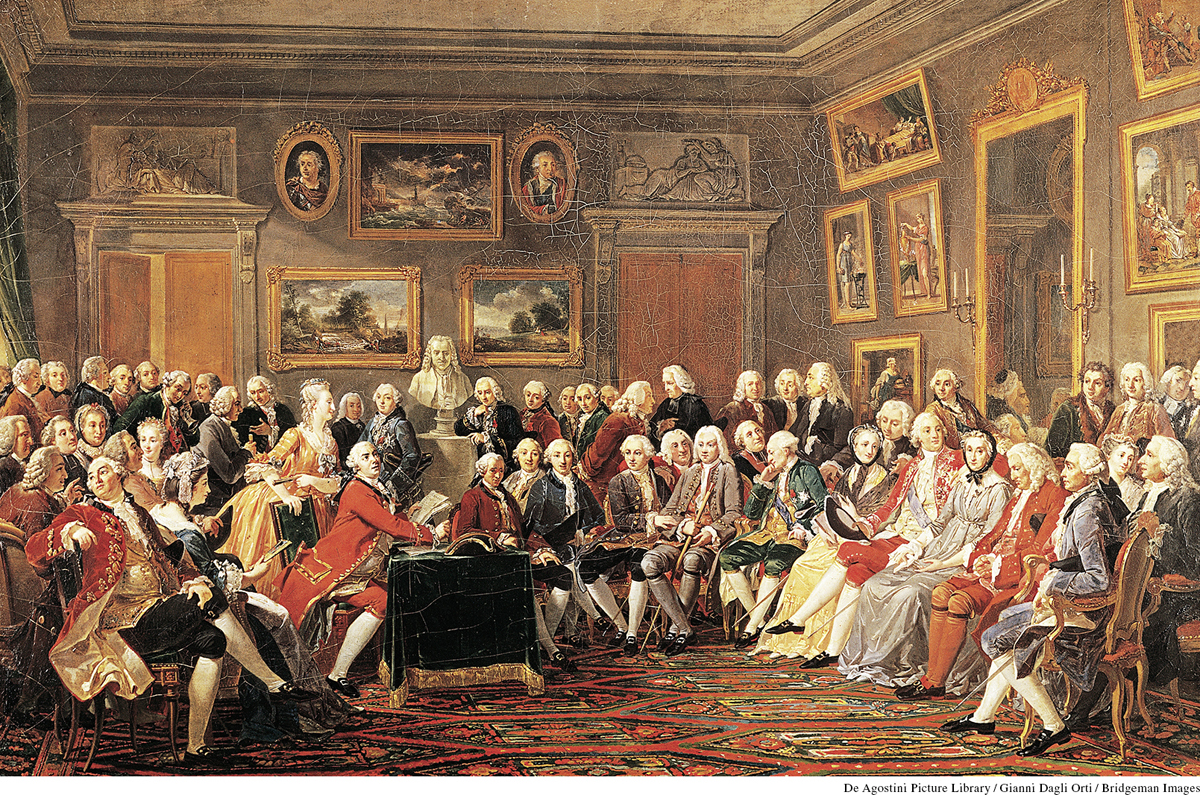

Few of the leading writers held university positions. Enlightenment ideas developed instead through printed books and pamphlets, through hand-copied letters that were circulated and sometimes published, and through informal readings of manuscripts. Salons—informal gatherings, usually sponsored by middle-class or aristocratic women—gave intellectual life an anchor outside the royal court and the church-controlled universities (see page 534). In the Parisian salons of the eighteenth century, the philosophes could discuss ideas they might hesitate to put into print. Best known was the salon of Madame Marie-Thérèse Geoffrin (1699–1777), a wealthy middle-class widow. She corresponded extensively with influential people across Europe, including Catherine the Great. Women’s salons helped galvanize intellectual life and reform movements all over Europe. Wealthy Jewish women created nine of the fourteen salons in Berlin at the end of the eighteenth century, and Princess Zofia Czartoryska gathered around her in Warsaw the reform leaders of Poland-Lithuania. (See “Contrasting Views: Women and the Enlightenment.”)