The End of Monarchy

The End of Monarchy

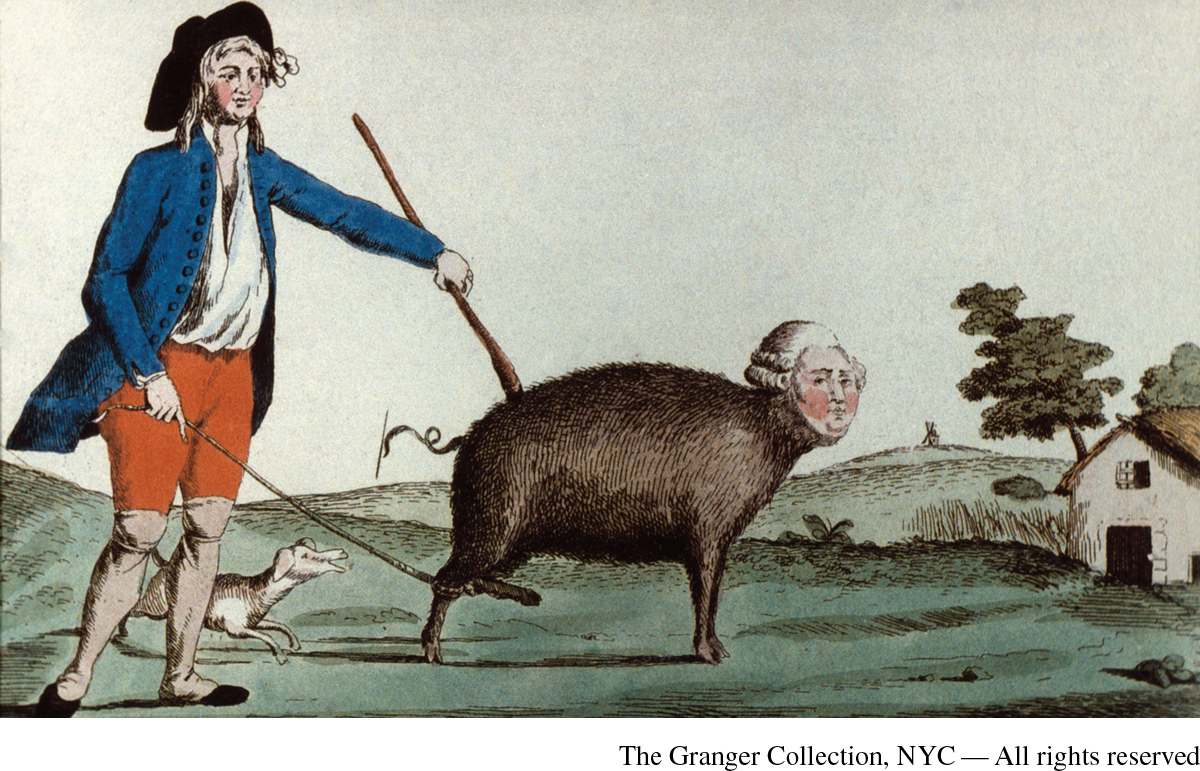

The reorganization of the Catholic church offended Louis XVI and gave added weight to those pushing him to organize resistance. On June 20, 1791, the royal family escaped in disguise from Paris and fled toward the eastern border of France, where they hoped to gather support from Austrian emperor Leopold II, the brother of Marie-Antoinette. The plans went awry when a postmaster recognized the king from his portrait on the new French money, and the royal family was arrested at Varennes, forty miles from the Austrian Netherlands border. The “flight to Varennes” touched off demonstrations in Paris against the royal family. Cartoons circulated depicting the royal family as animals being returned “to the stable.”

The constitution, finally completed in 1791, provided for the immediate election of a new legislature. The status of the king might have remained uncertain if war had not intervened, but by early 1792 everyone seemed intent on war with Austria. Louis and Marie-Antoinette hoped that such a war would lead to the defeat of the Revolution, whereas the deputies who favored a republic believed that war would lead to the king’s downfall. On April 21, 1792, Louis declared war on Austria. Prussia immediately entered on the Austrian side. Thousands of French aristocrats, including both of the king’s brothers and two-thirds of the army officer corps, had already emigrated and were gathering along France’s eastern border in expectation of joining a counterrevolutionary army.

When the fighting broke out, all the powers expected a short, relatively contained war. Instead, it would continue despite brief interruptions for the next twenty-three years. War had an immediate radicalizing effect on French politics. When the French armies proved woefully unprepared for battle, the authority of the new legislature came under fire. In June 1792, an angry crowd invaded the hall of the legislature in Paris and threatened the royal family. The Prussian commander, the duke of Brunswick, issued a manifesto announcing that Paris would be totally destroyed if the royal family suffered any violence.

The sans-culottes of Paris did not passively await their fate. Faced with the threat of military retaliation and frustrated with the inaction of the deputies, on August 10 the sans-culottes organized an insurrection and attacked the Tuileries palace, the residence of the king. The king and his family had to seek refuge in the meeting room of the legislature, where the frightened deputies ordered elections for a constitutional convention. By abolishing the property qualifications for voting, the deputies instituted universal male suffrage for the first time.

Violence soon exploded again when early in September 1792 the Prussians approached Paris. Hastily gathered mobs stormed the overflowing prisons to seek out traitors, and eleven hundred inmates were killed, including many ordinary and completely innocent people. The princess of Lamballe, one of the queen’s favorites, was hacked to pieces and her mutilated body displayed beneath the windows where the royal family was kept under guard. These “September massacres” showed the dark side of popular revolution, in which the common people demanded retribution against supposed enemies and conspirators.

When it met, the National Convention abolished the monarchy and on September 22 established the first republic in French history. The republic would answer only to the people, not to any royal authority. Many of the deputies in the Convention belonged to the devotedly republican (and therefore left-wing) Jacobin Club, named after the former monastery in Paris where the club had first met in 1789. The Jacobin Club in Paris headed a national political network of clubs that linked all the major towns and cities. Lafayette and other liberal aristocrats who had supported the constitutional monarchy fled into exile.

The National Convention faced a dire situation. It needed to write a new constitution for the republic while fighting a war with external enemies and confronting increasing resistance at home. The French people had never known any government other than monarchy. Only half the population could read and write at even a basic level. In this situation, symbolic actions became very important. Revolutionaries soon pulled down statues of kings and burned reminders of the former regime.

The fate of Louis XVI and the direction of the republic divided the deputies elected to the National Convention. Most of the deputies were middle-class lawyers and professionals who had developed their ardent republican beliefs in the network of Jacobin Clubs. After the fall of the monarchy in August 1792, however, the Jacobins had divided into two factions. The Girondins (named after a department in southwestern France, the Gironde, which provided some of its leading orators) met regularly at the salon of Jeanne Roland, the wife of a minister. They resented the growing power of Parisian militants and tried to appeal to the departments outside of Paris. The Mountain (so called because its deputies sat in the highest seats of the National Convention), in contrast, was closely allied with the Paris militants.

REVIEW QUESTION Why did the French Revolution turn in an increasingly radical direction after 1789?

The first showdown between the Girondins and the Mountain was the trial of the king in December 1792. Although the Girondins agreed that the king was guilty of treason, many of them argued for clemency, exile, or a popular referendum on his fate. After a long and difficult debate, the National Convention supported the Mountain and voted by a very narrow majority to execute the king. Louis XVI went to the guillotine on January 21, 1793, sharing the fate of Charles I of England in 1649.