Introduction for Chapter 21

IN 1830, THE LIVERPOOL AND MANCHESTER Railway Line opened to the cheers of crowds and the congratulations of government officials, including the duke of Wellington, the hero of Waterloo who had been named British prime minister. In the excitement, some of the dignitaries gathered on a parallel track. Another engine, George Stephenson’s Rocket, approached at high speed—the engine could go as fast as twenty-seven miles per hour. Most of the gentlemen scattered to safety, but former cabinet minister William Huskisson fell and was hit. A few hours later he died, the first official casualty of the newfangled railroad.

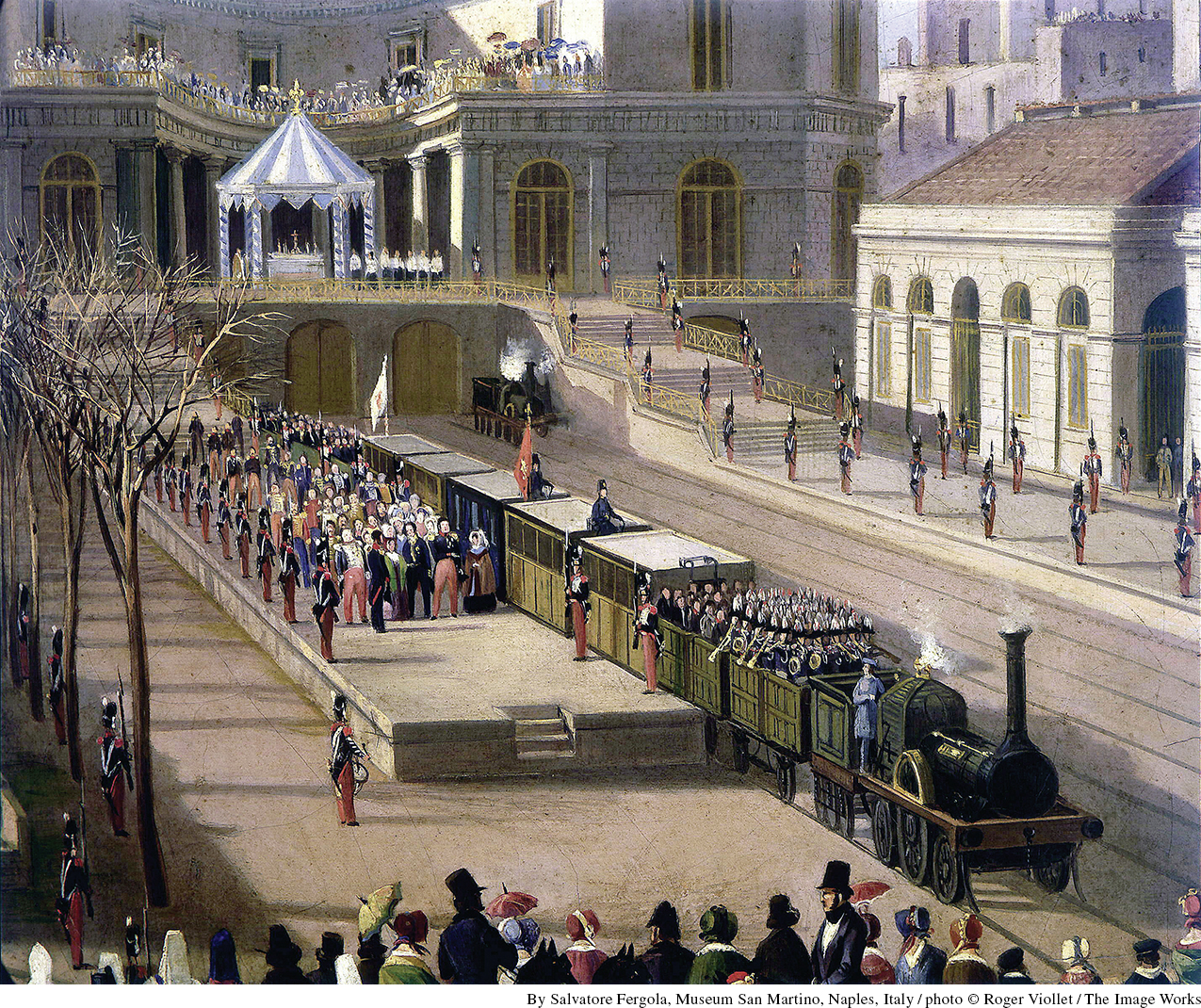

Dramatic and expensive, railroads were the most striking symbol of the new industrial age. Industrialization and its by-product of rapid urban growth fundamentally changed political conflicts, social relations, cultural concerns, and even the landscape. So great were the changes that they are collectively labeled the Industrial Revolution. Although this revolution did not take place in a single decade like the French Revolution, the introduction of steam-driven machinery, large factories, and a new working class transformed life in the Western world.

The shock of industrial and urban growth generated an outpouring of commentary on the need for social reforms. Many who wrote on social issues expected middle-class women to organize their homes as a domestic haven from the heartless process of upheaval. Yet despite the emphasis on domesticity, middle-class women participated in public issues, too: they set up reform societies that fought prostitution and helped poor mothers, they agitated for temperance (abstention from alcohol), and they joined the campaigns to abolish slavery.

CHAPTER FOCUS How did the Industrial Revolution create new social and political conflicts?

Social ferment set the ideological pots to a boil. A word coined during the French Revolution, ideology refers to a coherent set of beliefs about the way the social and political order should be organized. The dual impact of the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution prompted the development of a whole spectrum of ideologies to explain the meaning of the changes taking place. Nationalists, liberals, socialists, and communists offered competing visions of the social order they desired: they all agreed that change was necessary, but they disagreed about both the means and the ends of change. Their contest came to a head in 1848 when the rapid transformation of European society led to a new set of revolutionary outbreaks, more consuming than any since 1789.