Conclusion

Conclusion

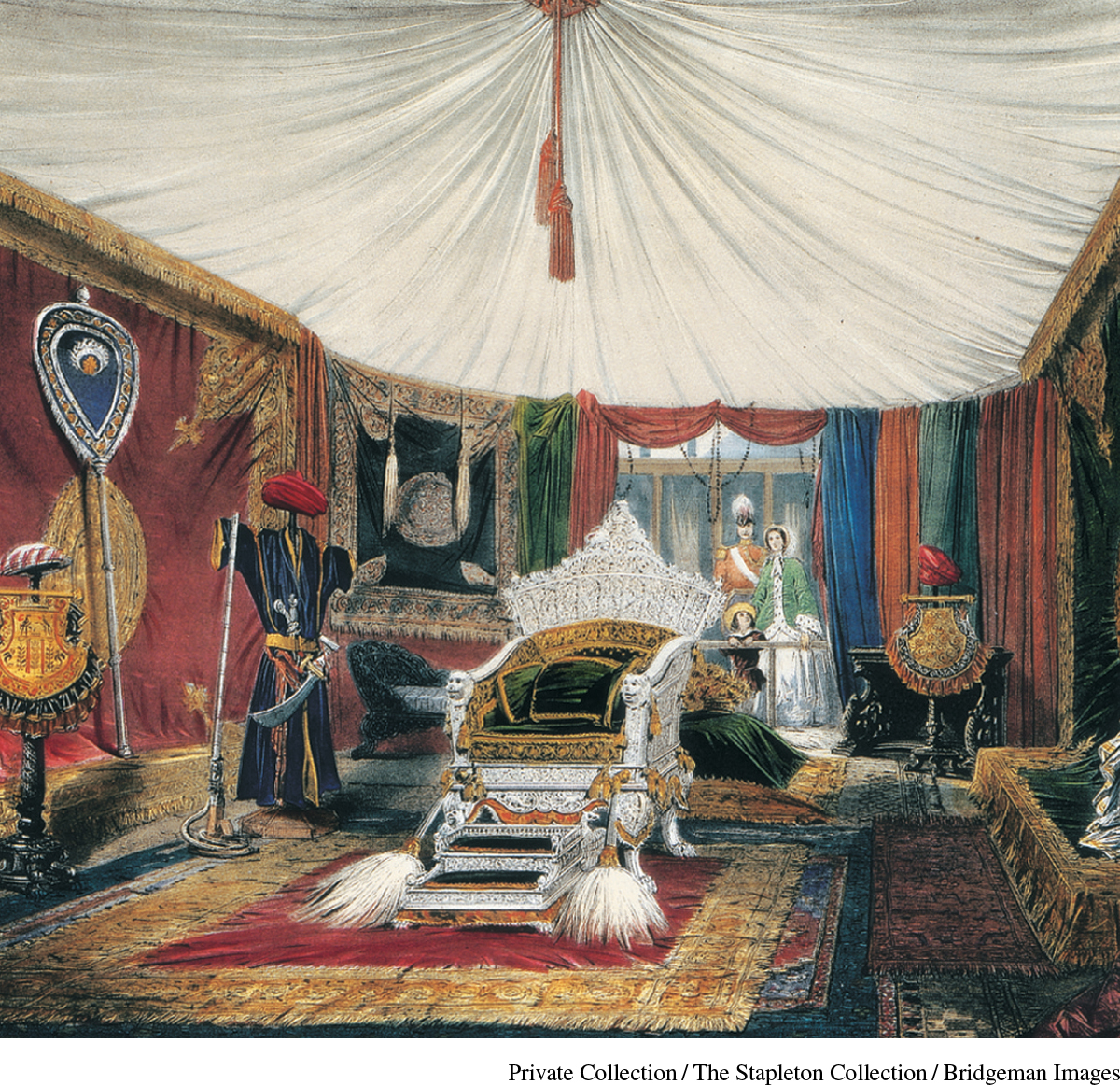

In 1851, Europe’s most important female monarch presided over a midcentury celebration of peace and industrial growth that helped dampen the still-smoldering fires of revolutionary passion. In the place of revolutionary fervor was a government-sponsored spectacle of what industry, hard work, and technological imagination could produce. Queen Victoria (r. 1837–1901), who herself promoted the notion of domesticity as women’s sphere, opened the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in London on May 1. A huge iron-and-glass building housed the display. Soon people referred to it as the Crystal Palace; its nine hundred tons of glass created an aura of fantasy, and the abundant goods from around the world inspired satisfaction and pride.

Many of the six million people who visited the Crystal Palace display traveled on the new railroads, the foremost symbol of the age of industrial transformation. Along with the railroads, the application of steam engines to textile manufacturing set in motion a host of economic and social changes: cities burgeoned with rapidly growing populations; factories concentrated laborers who formed a new working class; manufacturers now challenged landed elites for political leadership; and social problems galvanized reform organizations and governments alike. The Crystal Palace presented the rosy view of modern, industrial, urban life, but the housing shortages, inadequacy of water supplies, and recurrent epidemic diseases had not disappeared.

The revolutions of 1848 brought to the surface the profound tensions within a European society in transition toward industrialization and urbanization. After them, the Industrial Revolution continued and workers developed more extensive organizations. Confronted with the menace of revolution, conservative elites now sought alternatives that would be less threatening to the established order and still permit some change. This search for alternatives became immediately evident in the question of national unification in Germany and Italy. National unification would hereafter depend not on speeches and parliamentary resolutions, but rather on what the Prussian leader Otto von Bismarck would call “iron and blood.”