Urbanization and Its Consequences

Urbanization and Its Consequences

Industrial development spurred urban growth, yet cities with little industry grew as well. Urbanization is the growth of towns and cities due to the movement of people from rural to urban areas. Here, too, Great Britain led the way: half the population of England and Wales was living in towns by 1850, while in France and the German states only about a quarter of the total population was urban. Both old and new cities teemed with rising numbers in the 1830s and 1840s; the population of Vienna ballooned by 125,000 between 1827 and 1847, and the new industrial city of Manchester grew by 70,000 just in the 1830s.

Massive emigration from rural areas, rather than births to women already living in cities, accounted for this remarkable increase. City life and new factories beckoned those faced with hunger and poverty, including immigrants from other lands: thousands of Irish emigrated to English cities, Italians went to French cities, and Poles flocked to German cities. Settlements sprang up outside the old city limits but gradually became part of the urban area. Cities incorporated parks, cemeteries, zoos, and greenways—all imitations of the countryside, which itself was being industrialized by railroads and factories.

The rapid influx of people caused serious overcrowding in the cities because the housing stock expanded much more slowly than the population did. In Paris, thirty thousand workers lived in lodging houses, eight or nine to a room, with no separation of the sexes. In 1847, in St. Giles, the Irish quarter of London, 461 people lived in just twelve houses. Men, women, and children with no money for fuel huddled together for warmth on piles of filthy rotting straw or potato peels.

Severe crowding worsened already dire sanitation conditions. Residents dumped refuse into streets or courtyards, and human excrement collected in cesspools under apartment houses. At midcentury, London’s approximately 250,000 cesspools were emptied only once or twice a year. Water was scarce and had to be fetched daily from nearby fountains. Parisians, on average, had enough water for only two baths annually per person (the upper classes enjoyed more baths, of course; the lower classes, fewer). In London, private companies that supplied water turned on pumps in the poorer sections for only a few hours three days a week. In rapidly growing British industrial cities such as Manchester, one-third of the houses contained no latrines. Human waste ended up in the rivers that supplied drinking water. The horses that provided transportation inside the cities left droppings everywhere, and city dwellers often kept chickens, ducks, goats, pigs, geese, and even cattle, as well as dogs and cats, in their houses. The result was a “universal atmosphere of filth and stink,” as one observer recounted.

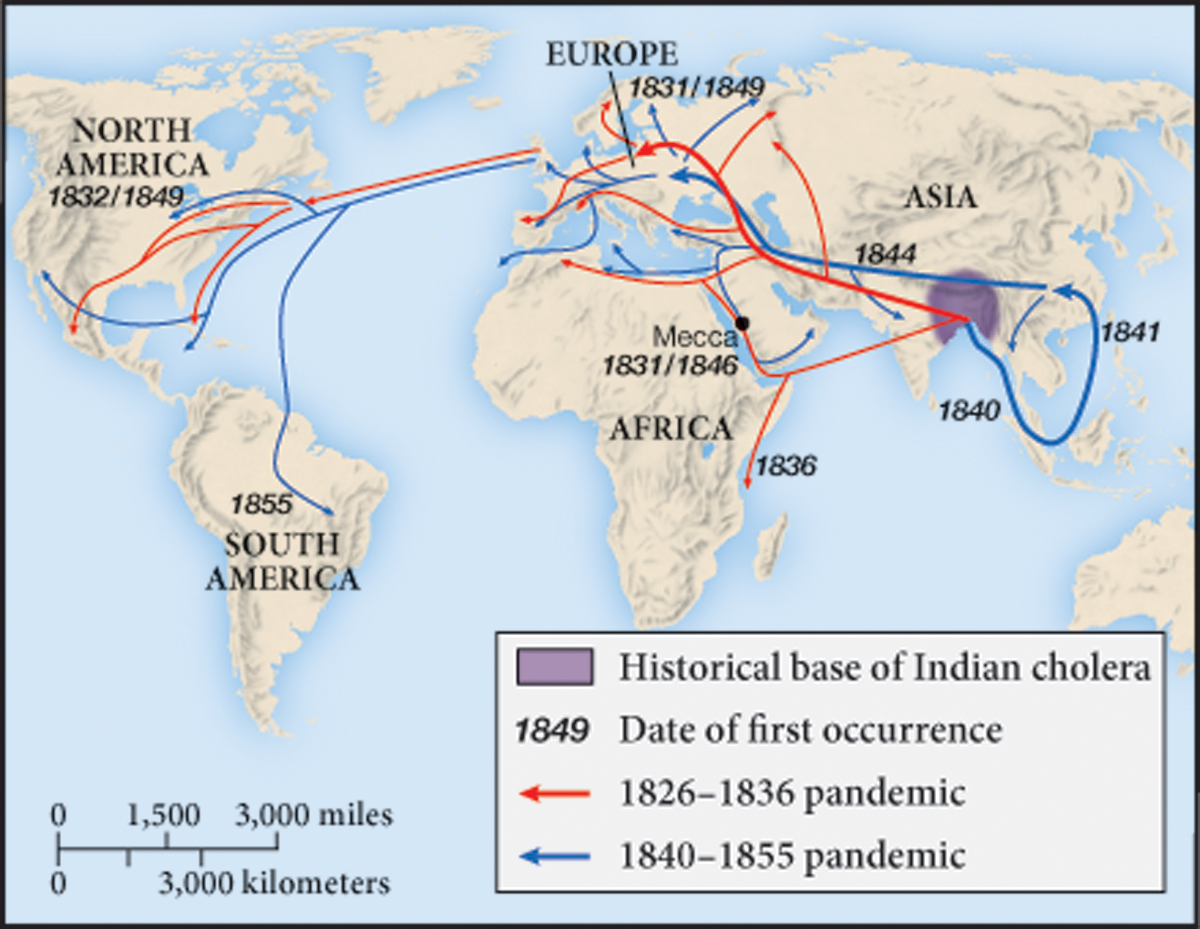

Such conditions made cities prime breeding grounds for disease. In 1830 to 1832 and again in 1847 to 1851, devastating outbreaks of cholera swept across Asia and Europe, touching the United States as well in 1849 to 1850 (Map 21.2). Today we know that a waterborne bacterium causes cholera, but at the time no one understood the disease and everyone feared it. The usually fatal illness induced violent vomiting and diarrhea and left the skin blue, eyes sunken and dull, and hands and feet ice cold. While cholera particularly ravaged the crowded, filthy neighborhoods of rapidly growing cities, it also claimed many rural and some well-to-do victims. In Paris, 18,000 people died in the 1832 epidemic and 20,000 in that of 1849; in London, 7,000 died in each epidemic; and in Russia, the epidemic was catastrophic, claiming 250,000 victims in 1831 to 1832 and 1 million in 1847 to 1851.

Epidemics revealed the social tensions lying just beneath the surface of urban life. Middle-class reformers often considered the poor to be morally degenerate. In their view, overcrowding led to sexual promiscuity and illegitimacy. They depicted the lower classes as dangerously lacking in sexual self-control. Officials collected statistics on illegitimacy that seemed to bear out these fears: one-quarter to one-half of the babies born in the big European cities in the 1830s and 1840s were illegitimate, and alarmed medical men wrote about thousands of infanticides. In contrast, only a tiny fraction of rural births were illegitimate. The rising rate of births outside of marriage seemed to go hand in hand with drinking and crime. Beer halls and pubs dotted the urban landscape. By the 1830s, Hungary’s twin cities of Buda and Pest had eight hundred beer and wine houses for the working classes. Police officials estimated that London had seventy thousand thieves and eighty thousand prostitutes. In many cities, nearly half the population lived at the level of bare subsistence, and increasing numbers depended on public welfare, charity, or criminality to make ends meet. (See “Seeing History: Visualizing Class Differences.”)

Everywhere reformers warned of a widening separation between rich and poor and a growing sense of hostility between the classes. A Swiss pastor noted: “A new spirit has arisen among the workers. Their hearts seethe with hatred of the well-to-do; their eyes lust for a share of the wealth about them; their mouths speak unblushingly of a coming day of retribution.” In 1848, as we will see, it would seem that day of retribution had arrived.