Power Politics in Central and Eastern Europe

Power Politics in Central and Eastern Europe

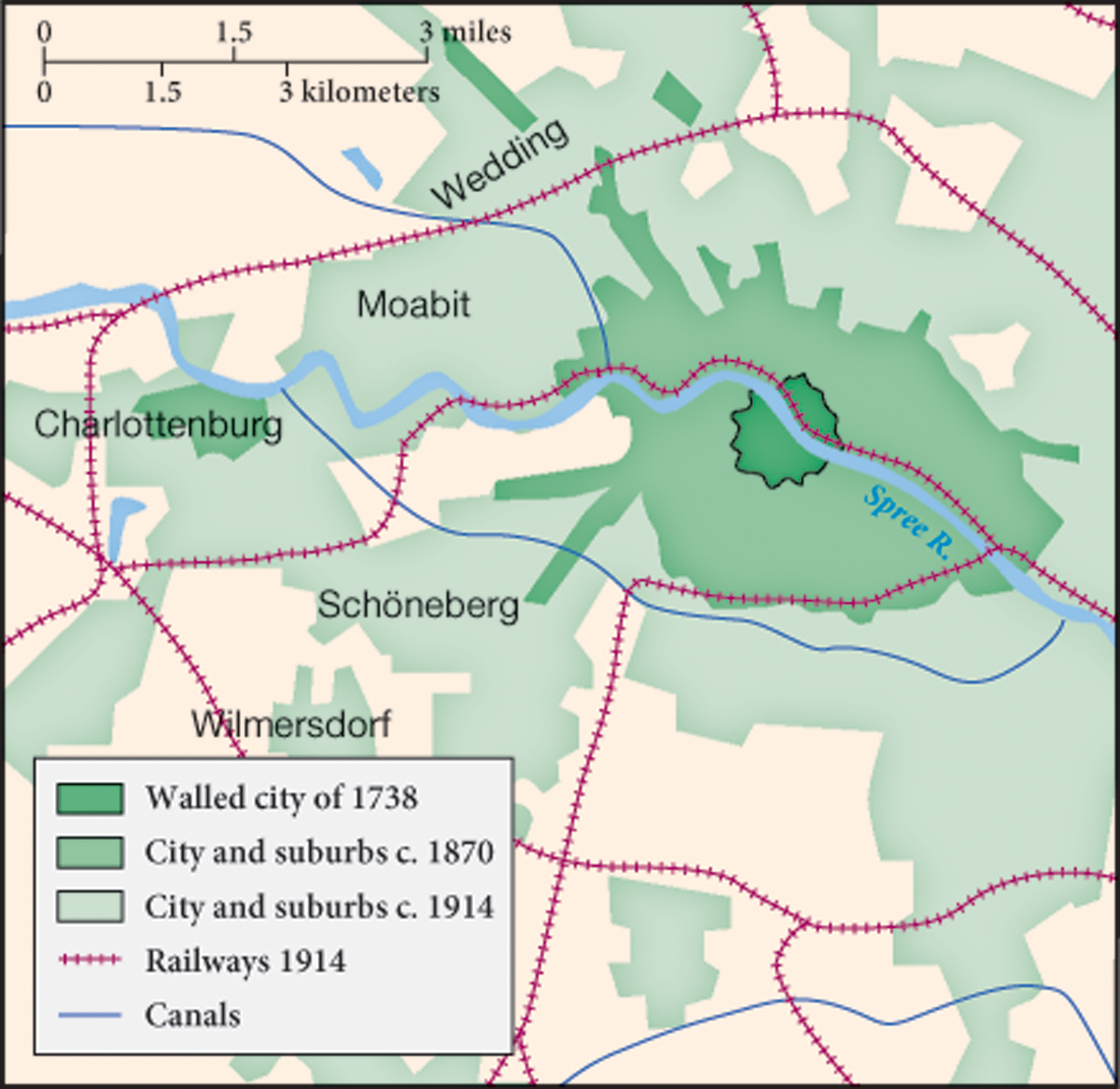

Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia diverged from the political paths taken by western European countries in the decades 1870–1890. In all three countries, conservative large landowners remained powerful, often blocking improvements in transport, sanitation, and tariff policy that would support a growing urban population. But Bismarck, who had upset the European balance of power by humiliating France in the Franco-Prussian War, created a powerful, unified Germany, with explosive economic growth and rapid development of every aspect of the nation-state, from transport to the thriving capital city of Berlin (Map 23.3).

His goals achieved, Bismarck now desired stability built on diplomacy instead of war. Needing peace to consolidate the new nation, he pronounced Germany “satisfied,” meaning that it sought no new territory in Europe. To ensure Germany’s long-term security, in 1873 Bismarck forged the Three Emperors’ League—an alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. The three conservative powers shared a commitment to maintaining the political status quo.

At home, Bismarck, who owned land and invested personally in industry, joined with the liberals to create a variety of financial institutions, including a central bank to advance German commerce and industry. After religious leaders defeated his Kulturkampf (see “Religion and National Order” in Chapter 22) against Catholicism, Bismarck turned to attacking socialists and liberals instead of Catholics as enemies of the regime. He outlawed the workers’ Social Democratic Party in 1878, and, hoping to lure the working class away from socialism, between 1882 and 1884 he sponsored an accident and disability insurance program—the first of its kind in Europe. In 1879, he put through tariffs protecting German agriculture and industry from foreign competition but also raising the prices of consumer goods, including food for ordinary people. Ending his support for laissez-faire economics, Bismarck broke with political liberals while simultaneously increasing the power of the agrarian conservatives by attacking the interests of Germany’s industrial sector.

Like Germany, Austria-Hungary frequently employed liberal economic policies and practices. From the 1860s, liberal businessmen succeeded in industrializing parts of the empire, and the prosperous middle classes erected conspicuously large homes, giving themselves a prominence in urban life that rivaled the aristocracy’s. They persuaded the government to enact free-trade provisions in the 1870s and to search out foreign investment to build up infrastructure, such as railroads.

Despite these measures, Austria-Hungary remained monarchist and authoritarian. Liberals in Austria—most of them ethnic Germans—saw their influence weaken under the leadership of Count Edouard von Taaffe, Austrian prime minister from 1879 to 1893. Building a coalition of clergy, conservatives, and Slavic parties, Taaffe used its power to weaken the liberals. In Bohemia, for example, he designated Czech as an official language of the bureaucracy and school system, thus breaking the German speakers’ monopoly on office holding. Reforms outraged individuals at whose expense other ethnic groups received benefits, yet those who won concessions, such as the Czechs, clamored for even greater autonomy. By playing nationalities off one another, the government ensured the monarchy’s central role in holding together competing interest groups.

Nationalists in the Balkans demanded independence from the declining Ottoman Empire, raising Austro-Hungarian fears and ambitions. In 1876, Slavs in Bulgaria and Bosnia-Herzegovina revolted against Turkish rule, killing Ottoman officials. As the Ottomans slaughtered thousands of Bulgarians in turn, two other small Balkan states, Serbia and Montenegro, rebelled against the sultan, too. Russian Pan-Slavic organizations sent aid to the Balkan rebels and so pressured the tsar’s government that Russia declared war on Turkey in 1877 in the name of protecting Orthodox Christians. With help from Romania and Greece, Russia defeated the Ottomans and by the Treaty of San Stefano (1878) created a large, pro-Russian Bulgaria.

The Treaty of San Stefano sparked an international uproar. Austria-Hungary and Britain feared that an enlarged Bulgaria would become a Russian satellite that would enable the tsar to dominate the Balkans. Austrian officials worried about an uprising of their own restless Slavs. British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli moved warships into position against Russia to halt the advance of Russian influence in the eastern Mediterranean, so close to Britain’s routes through the Suez Canal. The public was drawn into foreign policy: the music halls and newspapers of England echoed a new jingoism, or political sloganeering, that throbbed with militarism: “We don’t want to fight, but by jingo if we do, / We’ve got the ships, we’ve got the men, we’ve got the money too!”

The other great powers, however, did not want a Europe-wide war, and in 1878 they attempted to revive the concert of Europe by meeting at Berlin under the auspices of Bismarck—now a calming presence on the diplomatic scene. The Congress of Berlin rolled back the Russian victory by partitioning the large Bulgarian state carved out of Ottoman territory and denying any part of Bulgaria full independence from the Ottomans (Map 23.4). Austria occupied (but did not annex) Bosnia and Herzegovina as a way of gaining clout in the Balkans; Serbia and Montenegro became fully independent. The Balkans remained a site of ambition for independence and great-power rivalries.

Following the Congress of Berlin, the European powers attempted to guarantee stability through a complex series of alliances and treaties. Anxious about the Balkans, Austria-Hungary forged a defensive alliance with Germany in 1879. The Dual Alliance, as it was called, offered protection against Russia and its potential for inciting Slav rebellions. In 1882, Italy joined this partnership (henceforth called the Triple Alliance), largely because of Italy’s imperial rivalries with France. Bismarck negotiated the Reinsurance Treaty (1887) with Russia guaranteeing neutrality in case of war unless the Habsburgs attacked Russia or Germany attacked France. The intention was to keep the Habsburgs from recklessly starting a war over Pan-Slavism.

Russia itself was beset by domestic problems in the 1870s and 1880s. Young Russians were turning to revolution for solutions to political and social problems. One such group, the Populists, wanted to rouse debt-ridden peasants to revolt. Other people formed terrorist bands to assassinate public officials. The secret police rounded up hundreds of members of one of the largest groups, Land and Liberty, and subjected them to brutal torture and show trials. When in 1877 a young radical, Vera Zasulich, tried unsuccessfully to assassinate the chief of the St. Petersburg police, the people of the capital city applauded her act and acquittal, so great was their outrage at government treatment of young radicals from respectable families.

Writers debated Russia’s future, mobilizing public opinion over these issues. Novelists Leo Tolstoy, author of the epic War and Peace (1869), and Fyodor Dostoevsky, a former radical, believed that Russia above all required spiritual regeneration—not revolution. Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina (1877) tells the story of an impassioned love affair, but it also weaves in the spiritual quest of Levin, a former “progressive” landowner who, like Tolstoy, idealizes the peasantry’s stoic endurance. Dostoevsky satirized Russia’s radicals in The Possessed (1871), a novel in which a group of revolutionaries murders one of its own members. In Dostoevsky’s view, the radicals were simply destructive, offering no solutions whatsoever to Russia’s ills.

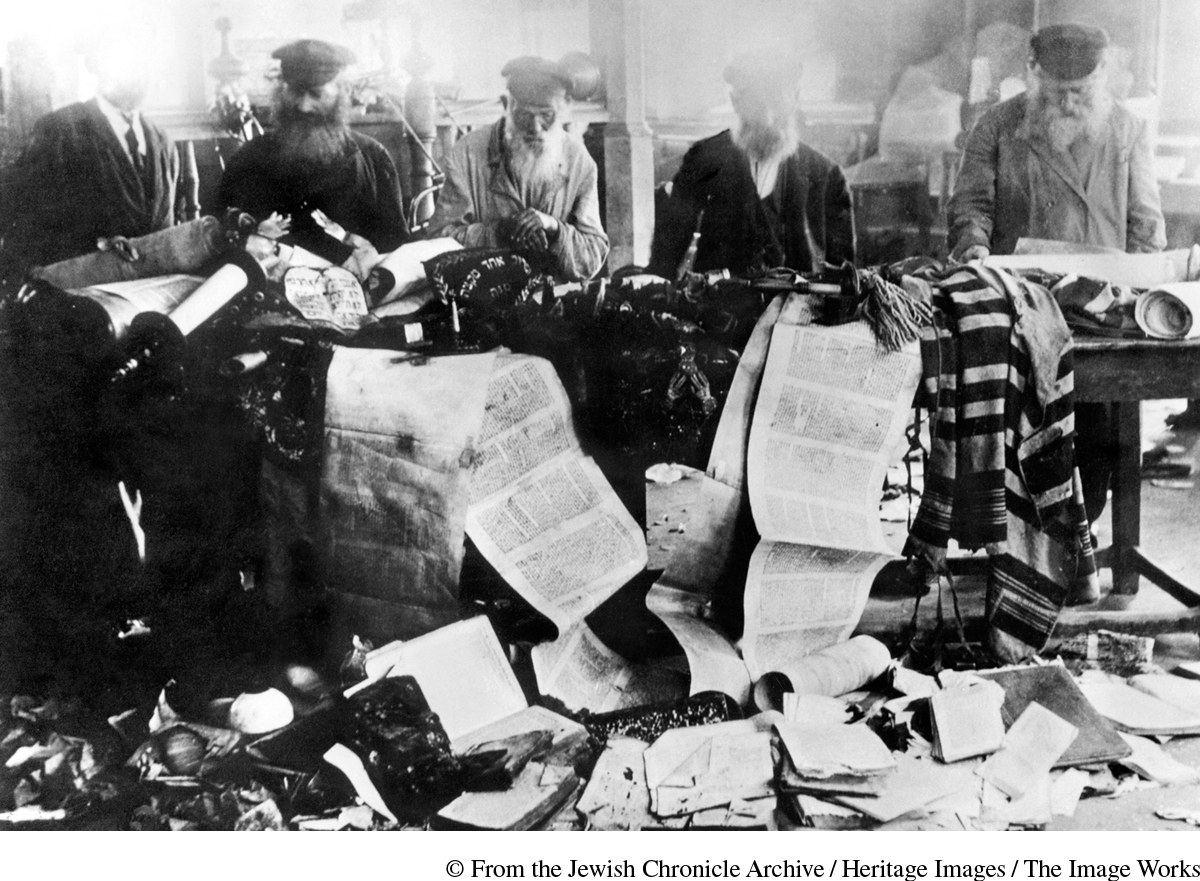

Despite the influential critiques published by Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, violent action rather than spiritual uplift remained the foundation of radicalism. In 1881, the People’s Will, a splinter group of Land and Liberty, killed Tsar Alexander II in a bomb attack. The tsar’s death, however, failed to provoke the general uprising the terrorists expected. Alexander III (r. 1881–1894) unleashed a new wave of oppression against religious and ethnic minorities. Popular books and drawings depicted Tatars, Poles, Ukrainians, and others as a horrifying menace to Russian culture. The five million Russian Jews, confined to the eighteenth-century Pale of Settlement (the name for the restricted territory in which they were permitted to live), endured pogroms. Their distinctive language, dress, and isolation in ghettos made them easy targets. Government administrators encouraged these pogroms, blaming Jews for rising living costs that were actually caused by the high taxes levied on peasants to pay for industrialization.

REVIEW QUESTION What were the major changes in political life from the 1870s to the 1890s, and which areas of Europe did they most affect?

As the tsar inflicted even greater repression across Russia, Bismarck’s delicate system of alliances of the three conservative powers was coming apart. A brash but deeply insecure young kaiser, William II (r. 1888–1918), came to the German throne in 1888. William resented Bismarck’s power, and his advisers flattered the young man into thinking that his own talent made Bismarck an unnecessary rival. William dismissed Bismarck in 1890 and let the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia lapse in favor of a pro-German relationship with Austria-Hungary. He thus destabilized the diplomatic scene just as imperial rivalries were intensifying among the European powers.