The Scramble for Africa—North and South

The Scramble for Africa—North and South

European countries had long viewed Africa—North and South—as a vast region for profit through trade and investment. In the late nineteenth century, they aimed for political control as well. Egypt, a convenient and profitable stop on the way to Asia, was an early target. Modernizing rulers had made Cairo into a bustling metropolis with lively commercial and manufacturing enterprises. Production of raw materials, such as cotton for European textile mills, was booming. Europeans invested heavily in the region, first in ventures such as building the Suez Canal in the 1860s, then in laying thousands of miles of railroad track, improving harbors, creating telegraph systems, and finally and most important, loaning money at exorbitant rates of interest.

In 1879, the British and the French took over the Egyptian treasury, allegedly to secure their investments and guarantee the repayment of loans. In 1882, they invaded the country with the excuse of squashing Egyptian nationalists who protested the takeover of the treasury. The British next seized control of the government as a whole and forcibly reshaped the Egyptian economy from a system based on multiple crops that maintained the country’s self-sufficiency to one that emphasized the production of a few crops—mainly cotton, raw silk, wheat, and rice—that cheaply fed both European manufacturing and the European working classes. Businessmen from the colonial powers, Egyptian landowners, and local merchants profited from these agricultural changes, while the bulk of the rural population barely eked out an existence.

Alongside the takeover of the Egyptian government, France occupied neighboring Tunisia in 1881. Europeans also turned their attention to sub-Saharan Africa. In the past, contact between Europe and Africa had principally involved the trade of African slaves for a variety of goods, but by this time Europeans had begun to want Africa’s raw materials, such as palm oil, cotton, metals, diamonds, cocoa, and rubber. Additionally, Britain needed the southern and eastern coasts of Africa for stopover ports on the route to Asia and its empire in India.

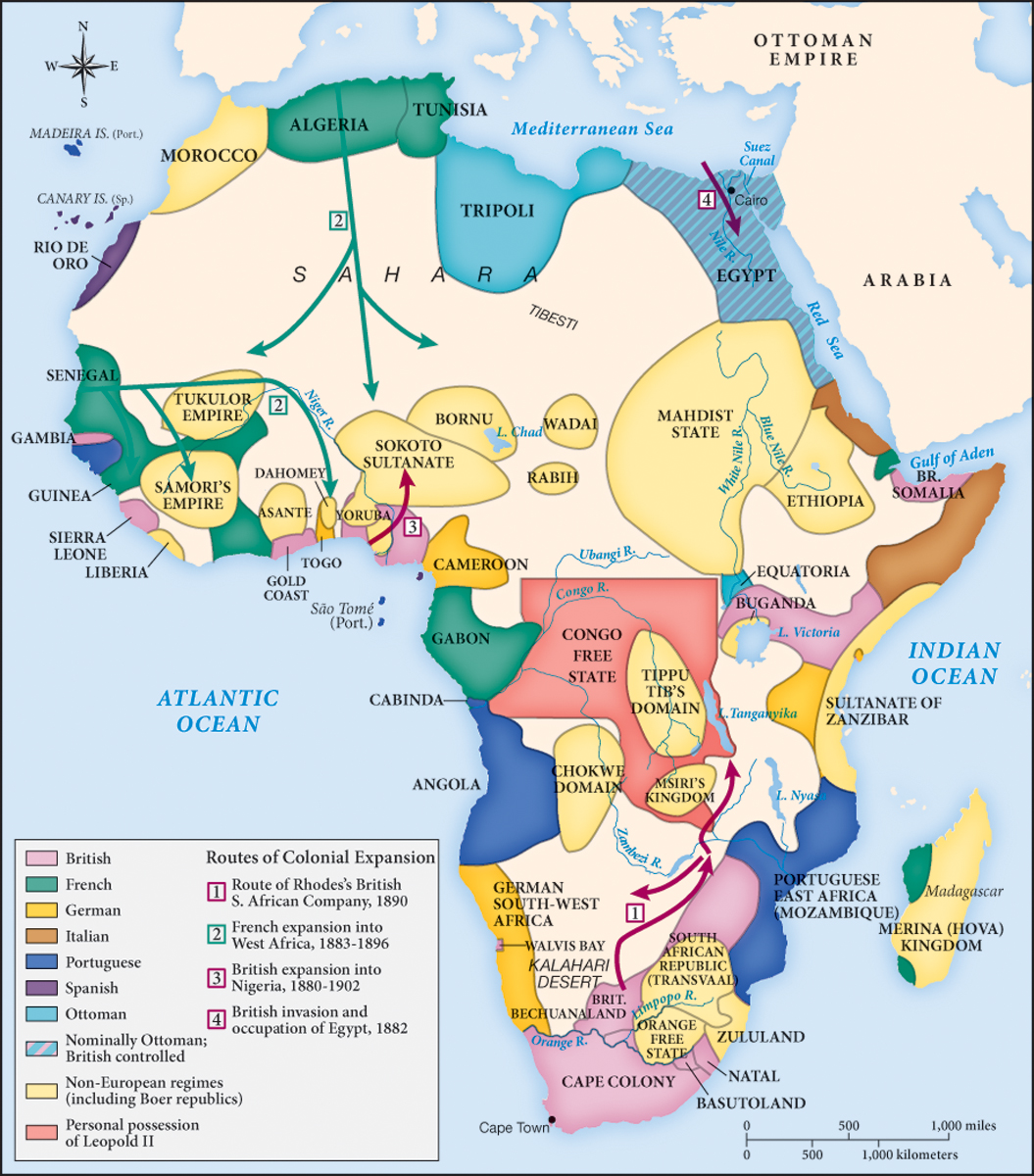

In the 1880s, European military forces conquered one sub-Saharan African territory after another (Map 23.1) to dominate peoples, land, and resources—“the magnificent cake of Africa,” as King Leopold II of Belgium (r. 1865–1909) put it. Insatiable greed drove Leopold to claim the Congo region of central Africa, inflicting on its peoples unparalleled acts of cruelty (see the illustration, “The Violence of Colonization”). German chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who saw colonies mostly as political bargaining chips, established German control over Cameroon and a section of East Africa, to which Frieda von Bülow and Carl Peters headed. Faced with competition, the British poured millions of pounds into conquering the continent “from Cairo to Cape Town,” as the slogan went, and the French cemented their hold on large portions of western Africa.

The scramble for Africa escalated tensions in Europe and prompted Bismarck to call a conference at Berlin. The European nations represented at the conference, held in a series of meetings in 1884 and 1885, decided that control of settlements along the African coast guaranteed rights to interior territory. This agreement led to the strictly linear dissection of the continent—a dissection that cut across boundaries of African culture and ethnic life. The Berlin conference also banned the sale of alcohol and controlled the flow of arms to African peoples. In theory, the meeting was supposed to reduce bloodshed and ambitions for territory in Africa. In reality, the agreement accelerated conquest of the continent and left everyone on edge over the threat of more violence. Newspaper accounts whetted the popular appetite for more takeovers. Music hall audiences rose to their feet and cheered at the sound of popular songs about imperial heroes of the day.

The lust for conquest had perhaps its greatest effect in southern Africa. The Dutch had moved into the area in the seventeenth century, but by 1815 the British had gained control. Thereafter, descendants of the Dutch, called Boers (Dutch for “farmers”), and British immigrants joined together in their fight to wrest farmland and mineral resources from the Xhosa, Zulu, and other African peoples. British businessman and politician Cecil Rhodes, sent to South Africa for his health just as diamonds were being discovered in 1870, cornered the diamond market and claimed a huge amount of African territory hundreds of miles into the interior. His ambition for Britain and for himself was boundless: “I contend that we are the finest race in the world,” he explained, “and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is.” Although notions of European racial superiority had been advanced before, Social Darwinism strengthened racism to justify the conquest of African lands.

Wherever necessary to ensure domination, Europeans either destroyed African economic and political systems or transformed them into instruments of their rule. A British governor of the West African region known as the Gold Coast put the matter succinctly in 1886: the British would “rule the country as if there were no inhabitants.” Indeed, most Europeans considered Africans barely civilized, despite the wealth local rulers and merchants accumulated in their international trade and despite individual Africans’ accomplishments in everything from fabric dyeing to road building and architecture. (See “Document 23.1: An African King Describes His Government.”) They felt this justified the confiscation of land from Africans, who were then forced to work for them to pay European-imposed taxes. Agriculture to support families, often performed by women and slaves, declined in favor of mining and farming cash crops. Men were made to leave their homes to work in mines or to build railroads. Family and community networks, though upset by the new arrangements, helped support Africans during this upheaval in everyday life.