The Trials of Empire

The Trials of Empire

Everyone was quick to violence when it came to empire, and Britain in its pursuit of the South African War (or Boer War) of 1899–1902 was no exception. In 1896, Cecil Rhodes, then prime minister of the Cape Colony in southern Africa, directed a raid into the neighboring territory of the Transvaal in hopes of stirring up trouble between the Boers, descendants of early Dutch settlers, and the more recent immigrants from Britain who had come to southern Africa in search of gold and other riches. Rhodes aimed for a British takeover of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, which the Boers independently controlled. The Boers, however, dealt Britain a bloody defeat.

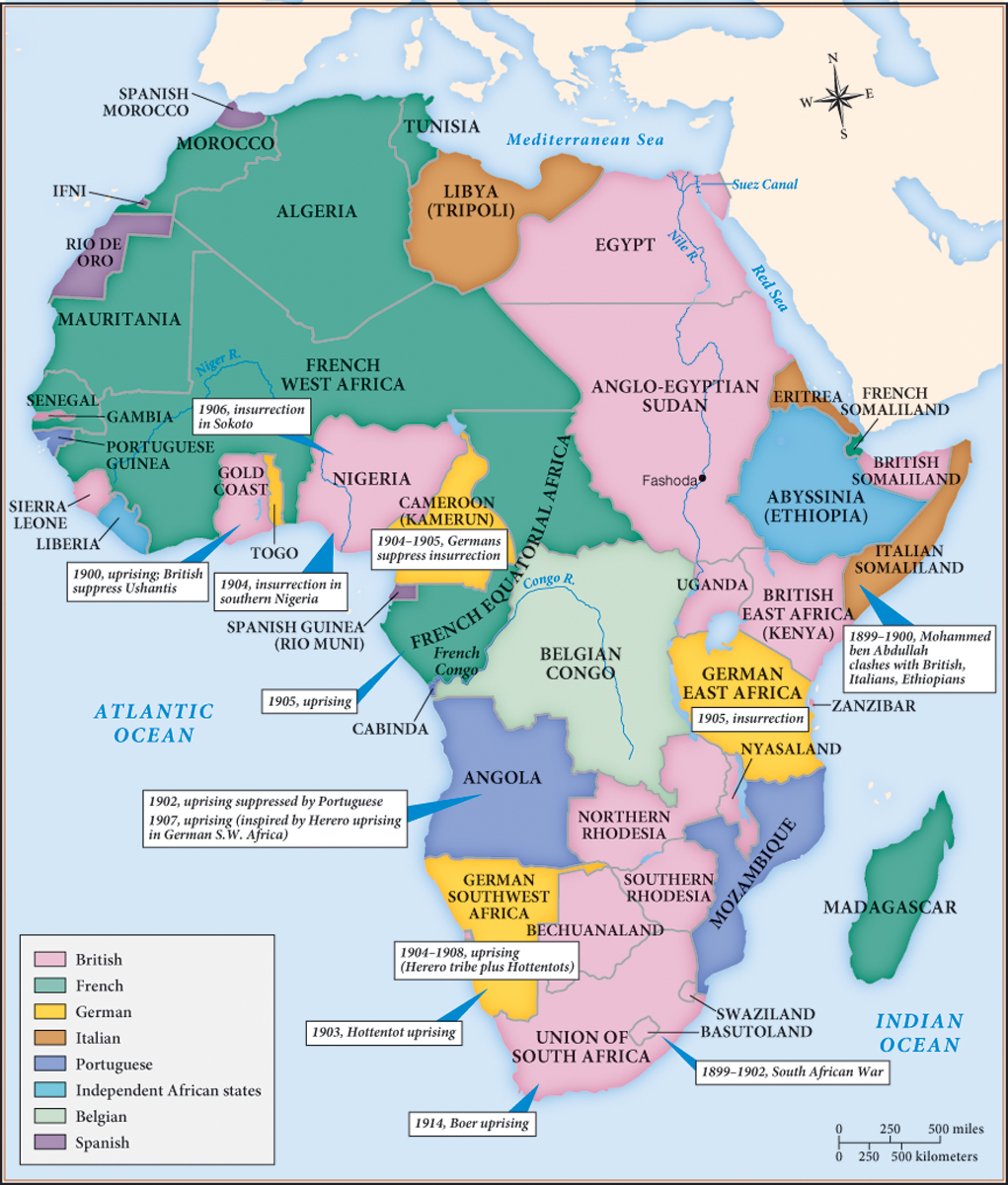

In 1899, Britain began full-scale operations against the Boers. Foreign correspondents covering the South African War reported on appalling bloodshed, the unfit condition of the average British soldier, and the inhumane treatment of South Africans herded into an unfamiliar institution—the concentration camp, which became the graveyard of tens of thousands, mostly women and children. Britain finally annexed the area after defeating the Boers in 1902, but prominent Britons began to call imperialism not the work of civilization but an act of barbarism (Map 24.2).

Nearly simultaneously with the South African War, the United States defeated Spain in the Spanish-American War in 1898 and took Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines as its trophies. Experienced in empire, the United States had successfully crushed native Americans and annexed Hawaii in 1898. Both Cuba and the Philippines had begun vigorous efforts to free themselves from Spanish rule before the war. Urged on by the inflammatory daily press, the United States went to war against Spain, but instead of allowing independence the U.S. government annexed Puerto Rico and Guam and bought the Philippines from Spain. Cuba was theoretically independent, but the United States monitored its activities.

The triumphant United States then waged a bloody war against the Filipinos, who wanted independence, not another imperial ruler. British poet Rudyard Kipling had encouraged the United States to “take up the white man’s burden” by bringing the benefits of Western civilization to those liberated from Spain. However, reports of American brutality in the Philippines, where 200,000 local people were slaughtered, disillusioned some in the Western public, who liked to imagine native peoples joyously welcoming the bearers of civilization.

Almost simultaneously, Italy won a costly victory over the Ottoman Empire in Libya, and Italian hopes rose for imperial grandeur in the future. Germany likewise joined the imperial contest, demanding an end to Britain’s and France’s domination among the colonial powers. German bankers and businessmen were active across Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, and by the turn of the century, Germany had colonies in Southwest Africa, the Cameroons, Togoland, and East Africa. Despite these successes, Germany, too, met humiliation and faced constant problems, especially in its dealings not only with Britain and France but also with local peoples in Africa and elsewhere who resisted the German takeover. As Italy and Germany joined the aggressive pursuit of new territory, the confident rule-setting for imperialism at the Berlin Conference a generation earlier was diluted by general anxiety, heated rivalry, and nationalist passion.

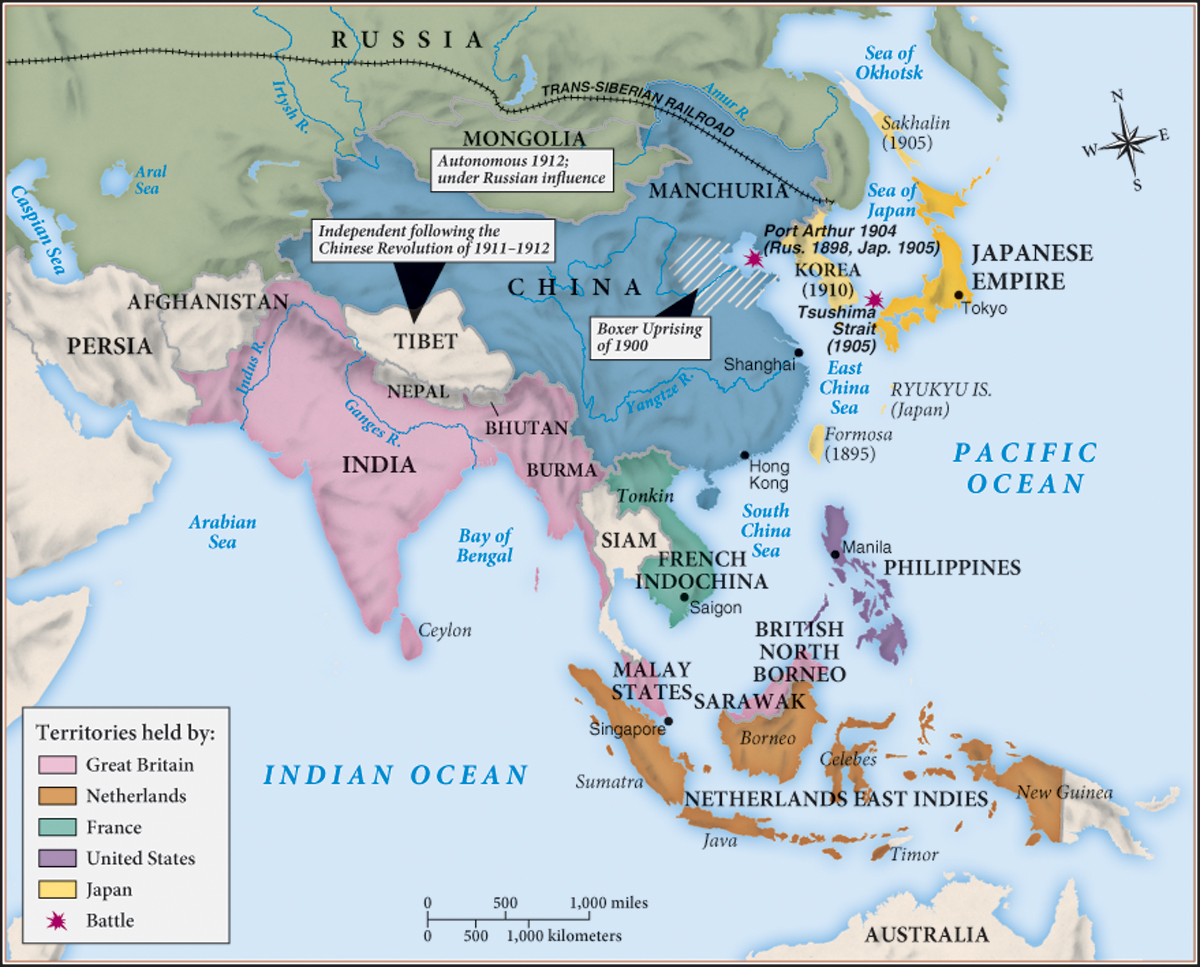

Japan’s rise as an imperial power further ate into Europeans’ confident approach to imperialism. Japan defeated China in 1894 in the Sino-Japanese War, which ended China’s domination of Korea. The European powers, alarmed by this victory, forced Japan to relinquish most of its gains, a move that outraged and insulted the Japanese. Japan’s insecurity had risen with Russian expansion of the Trans-Siberian Railroad through Manchuria, sending millions of Russian settlers eastward. Angered by the continuing presence of Russian troops in Manchuria, the Japanese attacked the tsar’s forces at Port Arthur in 1904 (Map 24.3).

The conservative Russian military proved inept in the ensuing Russo-Japanese War, even though it often had better equipment or strategic advantage. Russia’s Baltic Fleet sailed halfway around the globe only to be completely destroyed by Japan in the battle of Tsushima Strait (1905). The Russian defeat opened an era of Japanese domination in East Asian politics. As one English general observed, “I have today seen the most stupendous spectacle it is possible for the mortal brain to conceive—Asia advancing, Europe falling back.” Japan annexed Korea in 1910 and began to target other areas for colonization.