Sciences of the Modern Self

Sciences of the Modern Self

Scientists and Social Darwinists found cause for alarm not only in the poor condition of the working class but also in modern society’s mental complaints such as those of the Wolf-Man. New sciences of the mind such as psychology and psychoanalysis aimed to treat everyone, not just the insane. A number of books in the 1890s presented arguments on causes and cures for modern nervous ailments. Degeneration (1892–1893), by Hungarian-born physician Max Nordau, blamed overstimulation for both individual and national deterioration. According to Nordau, nervous complaints and the increasingly bizarre art world reflected a general downturn in the human species. The Social Darwinist remedy for such mental decline was imperial adventure for men and increased childbearing for both sexes because it would restore men’s virility and women’s femininity.

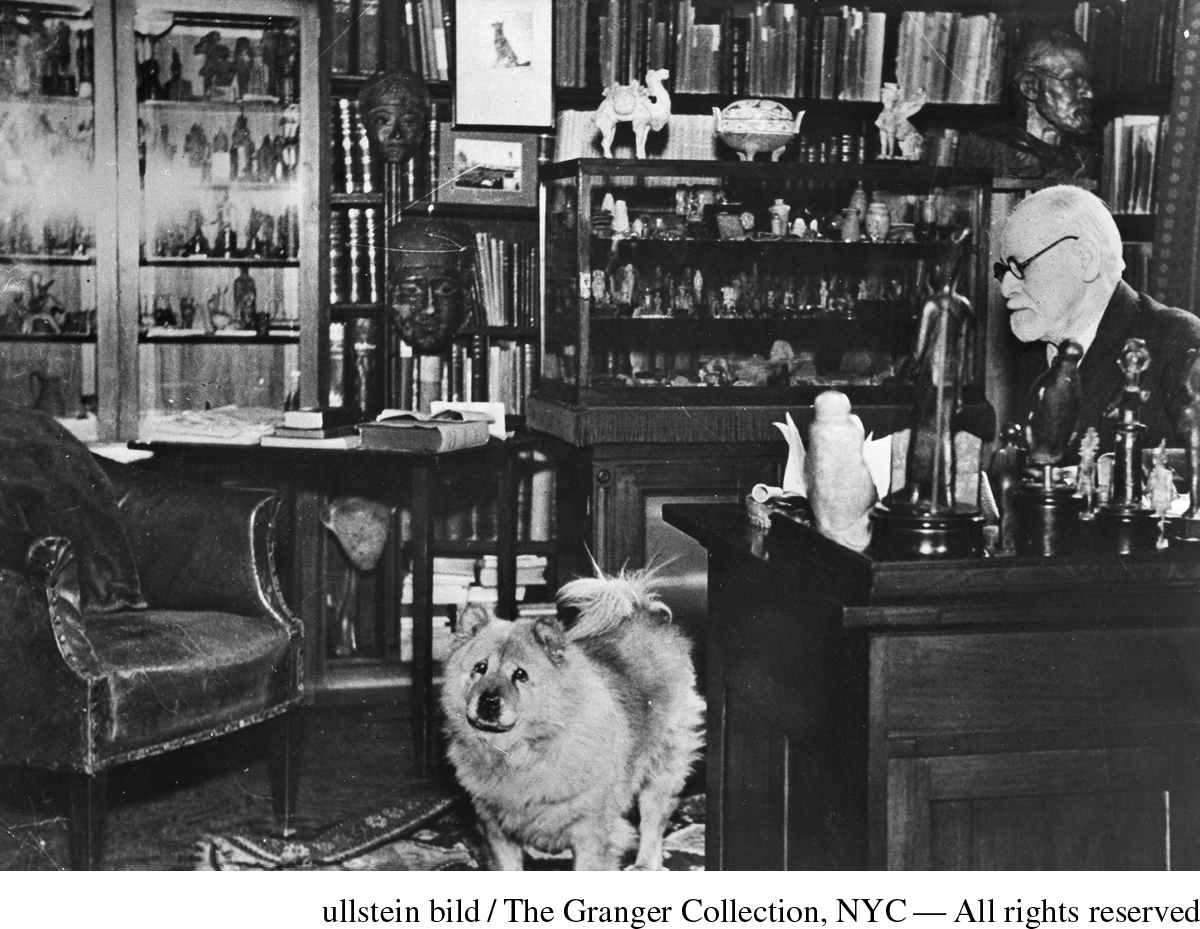

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) devised a different approach to treating mental problems—one that challenged the widespread liberal belief in a rational self that consistently acts in its own best interest. Dreams, he explained in The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), reveal an unseen and powerful part of one’s personality—the “unconscious”—where all sorts of desires are more or less hidden from one’s rational understanding. Freud also held that the human psyche is made up of three competing parts: the ego, the part that is most in touch with the need to work and survive—that is, reality; the id (or libido), the part that contains instincts and sexual energies; and the superego, the part that serves as the conscience. Freud’s theory of human mental processes and his method for treating their malfunctioning came to be called psychoanalysis.

Freud believed that sexual life should be understood objectively, free from religious or moral judgments. Children, he insisted, have sexual drives from the moment of birth; for the individual to attain maturity and for society to remain civilized, sexual desires—such as impulses toward incest—had to be repressed. Gender identity is more complicated than biology alone, he claimed, adding that girls and women have powerful sexual feelings, an idea that broke sharply with existing beliefs that women were passionless.

REVIEW QUESTION How did ideas about the self and about personal life change at the beginning of the twentieth century?

The influence of psychoanalysis became pervasive in the twentieth century. For example, Freud’s “talking cure,” as his method of treatment was quickly labeled, gave rise to a general acceptance of talking out one’s problems to a therapist. Terms such as neurotic and unconscious came into widespread use. Freud attributed girls’ complaints about sexual harassment or abuse to fantasy caused by “penis envy,” an idea that led members of the new profession of social work to believe that most instances of such abuse had not actually occurred. Like Darwin, Freud rejected optimistic views of the world, believing instead that humans individually and collectively were motivated by irrational drives toward death and destruction.