Revolution in Russia

Revolution in Russia

Of all the warring nations, Russia sustained the greatest number of casualties—7.5 million by 1917. In March,1 crowds of workingwomen swarmed the streets of Petrograd demanding relief from the harsh conditions. They soon fell in with other protesters commemorating International Women’s Day and were then joined by factory workers and other civilians. Instead of remaining loyal to the tsar, many soldiers were embittered by the massive casualties and their leaders’ foolhardy tactics. The government’s incompetence and Nicholas II’s stubborn resistance to change had made the war even worse in Russia than elsewhere. When the riots erupted in March 1917, Nicholas finally realized the situation was hopeless. He abdicated, bringing the three-hundred-year-old Romanov dynasty to a sudden end. (See “Document 25.1: Outbreak of the Russian Revolution.”)

Aristocratic and middle-class politicians from the old Duma formed a new administration called the Provisional Government. At first, hopes were high that under the Provisional Government, as one revolutionary poet put it, “our false, filthy, boring, hideous life should become a just, pure, merry, and beautiful life.” To survive, the Provisional Government had to pursue the war successfully, manage internal affairs better, and set the government on a firm constitutional footing, but other political forces had also strengthened during the revolution. Among them, the soviets—councils elected from workers and soldiers—competed with the government for political support. Born during the Revolution of 1905, the soviets in 1917 campaigned to end the deference usually given to the wealthy and to military officers, urged respect for workers and the poor, and temporarily gave an air of celebration and carnival to the political upheaval. The peasants, also competing for power, began to confiscate landed estates and withhold produce from the market, threatening the Provisional Government.

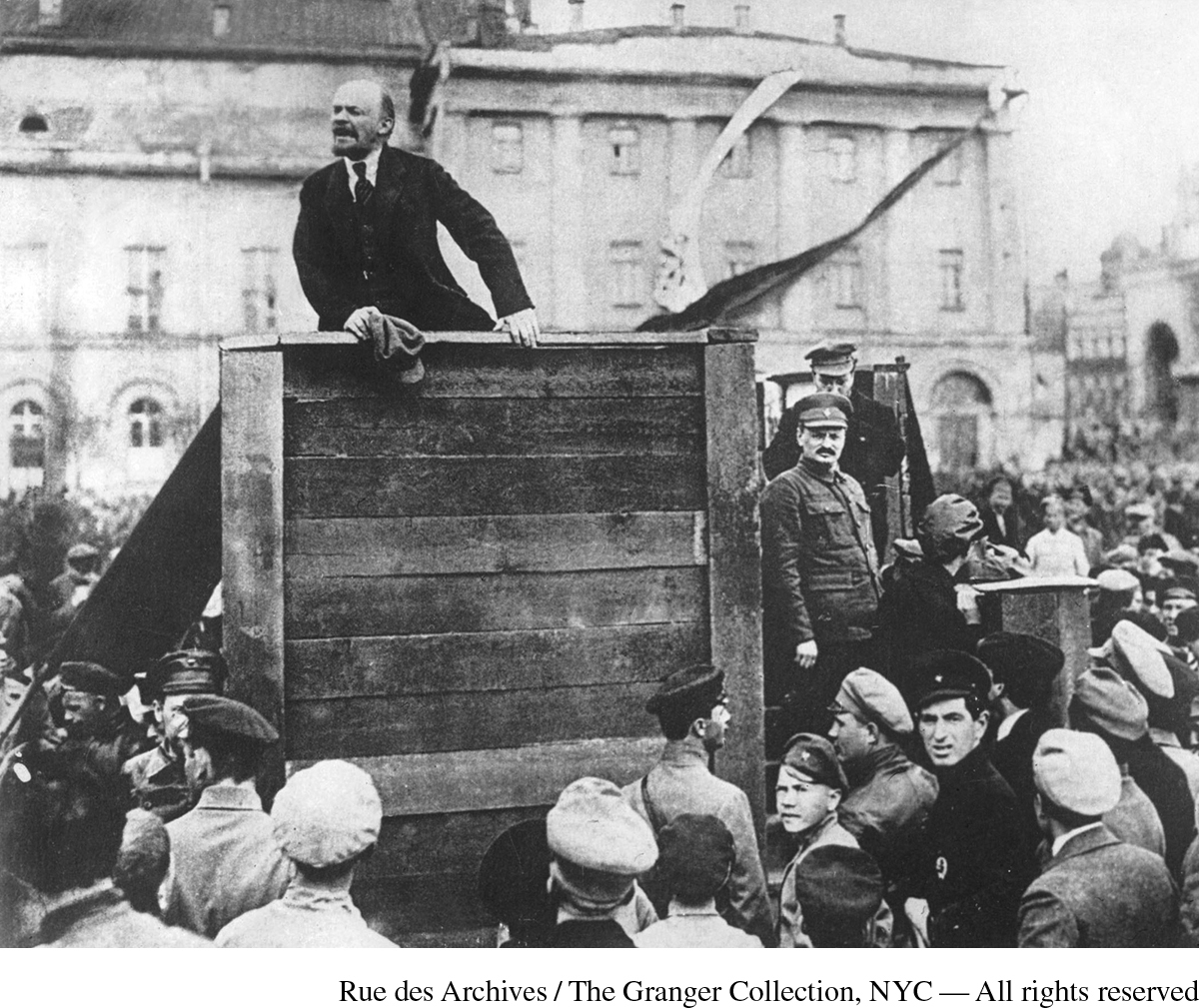

In hopes of adding to the turmoil in Russia, the Germans in April 1917 provided safe rail transportation for V. I. Lenin (1870–1924) and other prominent Bolsheviks to return to Russia through German territory. Lenin had devoted his entire existence to bringing about socialism through the force of his small band of Bolsheviks. Upon his return to Petrograd, he issued the April Theses, a radical document that called for Russia to withdraw from the war, for the soviets to seize power on behalf of workers and poor peasants, and for all private land to be nationalized. As the Bolsheviks aimed to supplant the Provisional Government, they employed such slogans as “All power to the soviets” and “Peace, land, and bread.”

New prime minister Aleksandr Kerensky used his commanding oratory to arouse patriotism, but he lacked the political skills needed to create an effective wartime government. The Bolshevik leadership, urged on by Lenin, overthrew the weakened Provisional Government in November 1917, an event called the Bolshevik Revolution. In January 1918, elections for a constituent assembly failed to give the Bolsheviks a plurality, so the party used troops to take over the new government completely. The Bolsheviks, observing Marxist doctrine, abolished private property and nationalized factories to stimulate production. The Provisional Government had allowed both men and women to vote in 1917, making Russia the first great power to legalize universal suffrage. This soon became a hollow privilege once the Bolsheviks limited the candidates to chosen members of the Communist Party.

The Bolsheviks asked Germany for peace and agreed to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918), which placed vast regions of the old Russian Empire under German occupation. Because the loss of millions of square miles to the Germans put Petrograd at risk, the Bolsheviks relocated the capital to Moscow and formally adopted the name Communists (taken from Karl Marx’s writings) to distinguish themselves from the socialists/social democrats who had voted for the disastrous war in the first place. Lenin called the catastrophic terms of the treaty “obscene.” However, he accepted them—not only because he had promised to bring peace to Russia but also because he believed that the rest of Europe would soon rebel against the war and overthrow the capitalist order.

A full-blown civil war now broke out in Russia, with the pro-Bolsheviks (or “Reds”) pitted against an array of forces (the “Whites”) who wanted to turn back the revolution (Map 25.2). Among the Whites were three distinct groups: the tsarist military leadership, composed mainly of landlords and supporters of aristocratic rule; the liberal educated class, including businessmen whose property had been nationalized; and non-Russian nationalities who saw their chance for independence. In addition, before World War I ended, Russia’s former allies—notably the United States, Britain, France, and Japan—landed troops in the country to fight the Bolsheviks. The counterrevolutionary groups lacked a strong leader and unified goals, however. Pro-tsarist forces, for example, alienated groups seeking independent nation-state status, such as the Ukrainians, Estonians, and Lithuanians, by stressing the goal of restoring the Russian Empire. Even with the presence of Allied troops, the opponents of revolution could not defeat the Bolsheviks without a common purpose.

The civil war shaped Russian communism. Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), Bolshevik commissar of war, built the highly disciplined army by ending democratic procedures, such as the election of officers, that had originally attracted soldiers to Bolshevism. Lenin and Trotsky introduced the policy of war communism—seizing grain from the peasantry to feed the civil war army and workforce. The Cheka (secret police) imprisoned political opponents and black marketers and often shot them without trial. The result was a more authoritarian government—a development that broke Marx’s promise that revolution would bring a “withering away” of the state.

As the Bolsheviks clamped down on their opponents during the bloody civil war, they organized their supporters to foster revolutionary Marxism across Europe. In March 1919, they founded the Third International, also known as the Communist International (Comintern), to replace the Second International with a centralized organization dedicated to preaching communism. By mid-1921, the Red Army had defeated the Whites in the Crimea, the Caucasus, and the Muslim borderlands in central Asia. After ousting the Japanese from Siberia in 1922, the Bolsheviks governed a state as multinational as the old Russian Empire had been, and one at odds with socialist promises for a humane and flourishing society.