Introduction for Chapter 26

WHEN ETTY HILLESUM MOVED to Amsterdam from the Dutch provinces in 1932 to attend law school, an economic depression gripped the world. A resourceful young woman, Hillesum pieced together a living as a housekeeper and part-time language teacher so that she could continue her studies. Absorbed in her everyday life, she took little note of Adolf Hitler’s spectacular rise to power in Germany, even when he demonized her fellow Jews as responsible for the economic slump and for virtually every other problem Germany faced. In 1939, the outbreak of World War II awakened her to the reality of what was happening. The German conquest of the Netherlands in 1940 led to the persecution of Dutch Jews, bringing Hillesum to note in her diary: “What they are after is our total destruction.” The Nazis started relocating Jews to camps in Germany and Poland. Hillesum went to work for Amsterdam’s Jewish Council, which was forced to organize the transport of Jews to these death camps. Changing from self-absorbed student to heroine, she did what she could to help other Jews and began carefully recording the deportations. When she and her family were captured and deported in turn, she smuggled out letters from the transit camps along the route to Poland, describing the inhumane conditions and brutal treatment of the Jews. “I wish I could live for a long time so that one day I may know how to explain it,” she wrote. Etty Hillesum never got her wish: she died at Auschwitz in November 1943.

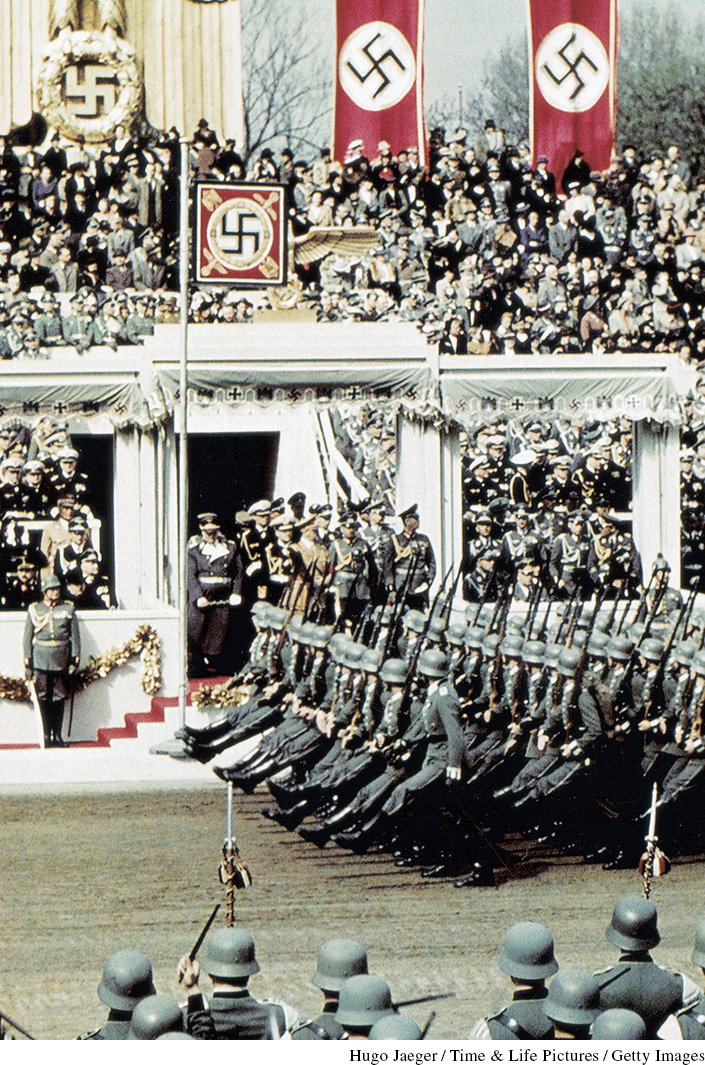

The economic recovery of the late 1920s came to a halt with the U.S. stock market crash in 1929, which launched a worldwide economic depression. Economic distress attracted many people to military-style strongmen for solutions to their problems. Among these dictators was Adolf Hitler, who called on the German masses to restore the national glory that had been damaged by defeat in 1918. He urged Germans to scorn democratic rights and root out those he considered to be inferior people: Jews, Slavs, and Sinti and Roma (often called Gypsies), among others. Militaristic and fascist regimes spread to Spain, Poland, Hungary, Japan, and countries of Latin America, crushing representative institutions. In the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin justified the killing of millions of citizens as necessary for the USSR’s industrialization and the survival of communism. For millions of hard-pressed people in the 1930s, dictatorship had great appeal.

CHAPTER FOCUS What were the main economic, social, and political challenges of the years 1929–1945, and how did governments and individuals respond to them?

Elected leaders in the democracies reacted cautiously to both economic depression and the dictators’ aggression. In an age of mass media, leaders following democratic principles appeared timid, while dictators dressed in uniforms looked bold and decisive. Only the German invasion of Poland in 1939 pushed the democracies to strong action, as World War II erupted in Europe. By 1941, the war had spread across the globe with the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and many other nations united in combat against Germany, Italy, Japan, and their allies. Tens of millions would perish in this war because both technology and ideology had become more deadly than they had been just two decades earlier. More than half the dead were civilians, among them Etty Hillesum, killed for being Jewish.