The German Onslaught

The German Onslaught

German forces quickly defeated the ill-equipped Polish troops by launching a Blitzkrieg (“lightning war”), in which they concentrated airplanes, tanks, and motorized infantry with overpowering force and speed. Blitzkrieg suggested to Germans at home that the costs of gaining Lebensraum would be low. On September 17, 1939, the Soviets invaded Poland from the east. By the end of the month, the victors had divided the country according to the Nazi-Soviet Pact. Nazi propagandists frightened Germans into supporting the conflict because of the “warlike menace” of world Jewry that supposedly threatened the nation’s very existence.

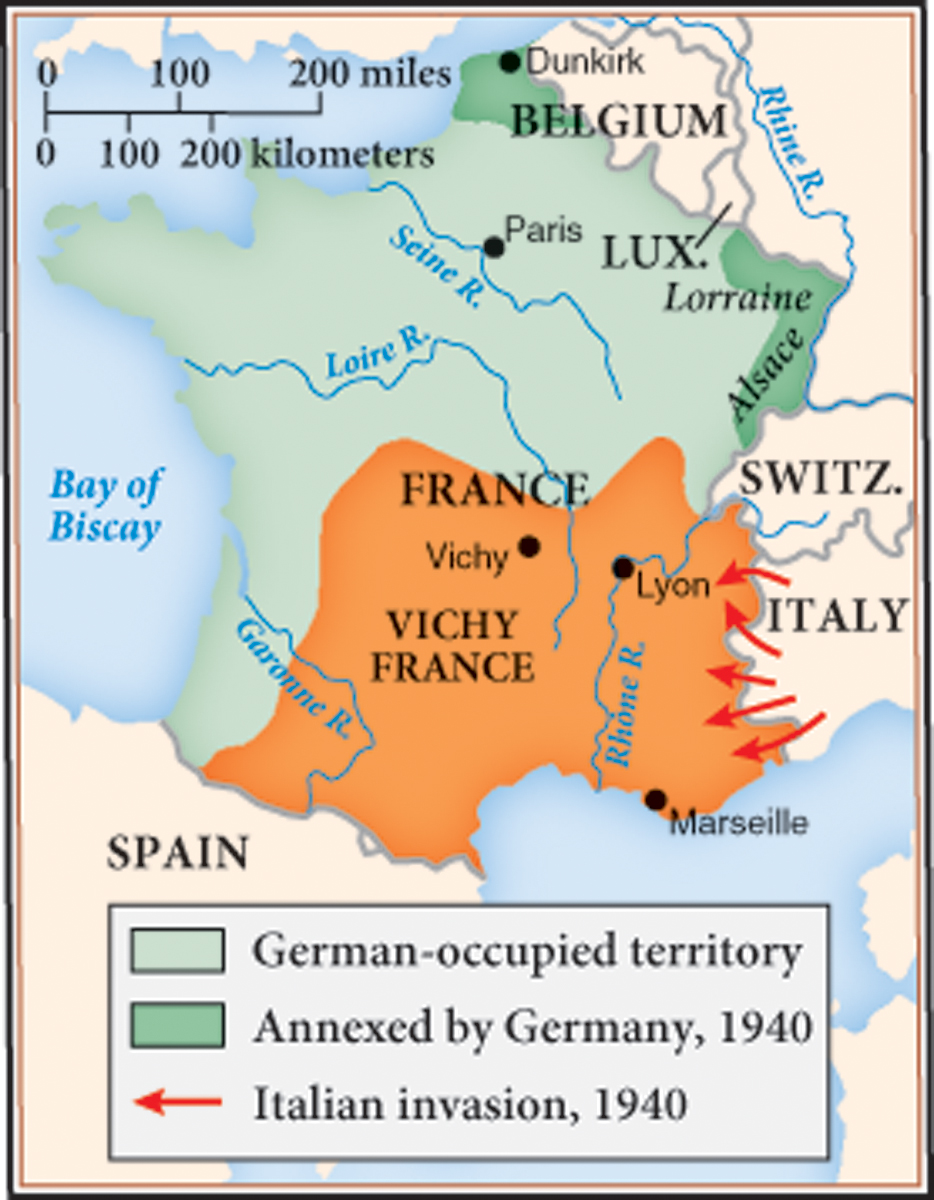

In April 1940, Blitzkrieg crushed Denmark and Norway; the battles of Belgium, the Netherlands, and France followed in May and June. On June 5, Mussolini, eyeing future gains for Italy, invaded France from the southeast. The French defense and its British allies could not withstand the German onslaught. Trapped on the beaches of Dunkirk in northern France, 370,000 French and British soldiers were rescued by an improvised fleet of naval ships, fishing boats, and pleasure craft. The French government surrendered on June 22, 1940, leaving Germany to rule the northern half of the country, including Paris. In the south, named Vichy France after the spa town where the government sat, the aged World War I hero Henri Philippe Pétain was allowed to govern because of his and his administration’s pro-Nazi values. Stalin used the diversion in western Europe to annex the Baltic states.

Britain now stood alone, installing as prime minister Winston Churchill (1874–1965), an early campaigner for resistance to Hitler. As Hitler ordered the bombardment of Britain in the summer of 1940, Churchill rallied the nation by radio to protect the ideals of liberty with “blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” In the battle of Britain—or Blitz, as the British called it—the German Luftwaffe (“air force”) bombed monuments, public buildings, weapons depots, and industry. In response, Britain poured resources into its highly successful code-breaking group called Ultra, further development of radar, and air weaponry, outproducing the Germans by 50 percent.

By the fall of 1940, German air losses compelled Hitler to abandon his plan for a naval invasion of Britain. Forcing Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria to join the Axis powers, Germany gained access to more food, oil, and other resources. He then made his fatal decision to break the Nazi-Soviet Pact and attack the Soviet Union—the “center of judeobolshevism,” he called it. In June 1941, three million German and other troops penetrated Soviet lines along a two-thousand-mile front; by July, they had rolled to within two hundred miles of Moscow. Using a strategy of rapid encirclement, German troops killed, captured, or wounded more than half the 4.5 million Soviet soldiers.

Amid success, Hitler blundered. Considering himself a military genius and the Slavic people inferior, he proposed attacking Leningrad, the Baltic states, and Ukraine simultaneously, even though his generals wanted to concentrate on Moscow. Driven by Stalin and local party members, the Soviet people fought back. The onset of winter turned Nazi soldiers into frostbitten wretches because Hitler had feared that equipping his army for Russian conditions would suggest to civilians that a long campaign lay ahead. Convinced of a quick victory in the USSR, he switched German production from making tanks and artillery to making battleships and airplanes for war beyond the Soviet Union. Consequently, Germany’s poorly supplied armies fell victim not only to the weather but also to a shortage of equipment. As the war became worldwide, Germany still had an inflated view of its own power.